Spanning a gamut of hard-strutting hip-hop, urban blues, lush R&B and the old-world spirituals of Thomas A. Dorsey, The 4th Wall acts like a third eye of African-American cognition.

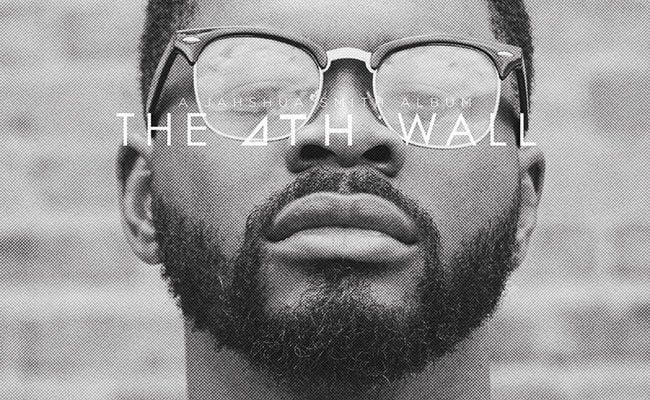

Detroit native Jahshua Smith is the voice you almost heard on a wider, corporate-endorsed level but then ultimately did not, thanks to his rather judicious side-stepping that had him continue his studies at Michigan State. Turning down a developmental deal with Universal Music may have the rapper’s contemporaries doing a double-take. But instead of trying to impress a boardroom full of suits, Smith opted to forge a career independently – a move which has allowed him to create and explore a brand of hip-hop which combines his worldly knowledge with smart urban grooves.

Smith is only two albums into his career. But he has already, in a short amount of time, managed to carve out his own personal space in hip-hop. His music is balanced on a sagacious tip, where he examines the rigmaroles of daily life through the Afrocentric prism of dialogue and debate. This isn’t exactly new in hip-hop. Smith, however, wants to make you think and dance — shed tears on the dancefloor, if you will. Delivering talk-medicine with an explosive dose of bone-shaking bass, the rapper is of the mind that what hits you hard at a corporeal level will also hit you soul-deep.

Riffing somewhat on the concept album, his sophomore effort, The 4th Wall, is a loose construct of television-inspired references. Picking up where his debut, The Final Season ended, Smith expands on the ideas of life being like a television series; The 4th Wall is one narrative in the phase of one man’s life, commenting on the current state of political affairs (the pressing issues of the Black Lives Matter movement) to the more intimate dealings of friendships and love. The fourth wall on Smith’s album is a barrier often dismantled and then re-erected in the constant engagement between audience and performer; the “you” that the rapper raps to (like in any popular song) is a perspective at once objective and, ironically, self-referential.

Spanning a gamut of hard-strutting hip-hop, urban blues, lush R&B and the old-world spirituals of Thomas A. Dorsey, The 4th Wall acts like a third eye of African-American cognition. Smith certainly speaks a frank dialogue on both the inequities and joys of contemporary black culture, but much of what he says is received through emotional discernment. The album hits the ground running with opening number “Don’t Forget It”, a mid-tempo thump with warm, airy synth waves radiating from the strolling groove. It boldly proclaims the album’s thesis and intent, outlining all the issues Smith will dissect for the next hour or so. The slow-grinding bass bang of “Superheroes” pulses with a tension that is galactic, the slips and dips of blues licks floating in the nebulous space of the dénouement.

Matters of sex also find their way into the rapper’s perimeters of personal disquisition. His talks of intimacy sound as though they are taking place behind the closed doors of clandestine spaces, all the while being secretly amplified to a listening and silent audience, unbeknownst to the parties directly involved. “Down”, a lushly mellow and funkified R&B groove, possibly doubles as a narrative for just simply chilling with a lady friend and (to a racier degree) cunnilingus. A sweeter, more innocuous affectation of love is demonstrated on “Josephine/Used to Have”, a breezy vibe pulsing gently with loping beats. Two thirds into the song, its addendum, “Used to Have” detours into an oddly shuffling loop of afterthoughts.

Numbers like “Changes Pt. 2″, “Not You” and “Grey Goose Quesadillas” pump out huge bass like a weaponized subwoofer, aiming infrasound death-rays onto a packed dancefloor. On “Changes Pt. 2″, beats drop like heavy boulders; curiously, from just behind in the near distance, you can hear the industrial rattles of a dockyard in a harbour. On “Not You”, Smith synchronizes the big, shuddering boom of his human heartbeat with the mechanical bass throb of an 808; here, his navel-gazing reflections turn the espousals of love into earnest doubt.

As an artist, Jahshua Smith may be relatively new in the game, compared to his far more prolific contemporaries. But he’s demonstrated a striking efficiency in his work, in which his keen wit is paralleled with the deep soul diving of his exploratory sound. The attraction of The 4th Wall is not only its luxuriant melodies and seductive grooves, but also the complex designs of Smith’s emotional proclivities, his science and artistry in creating, with his conscious hip-hop, a potent logic bomb.

***

Can you give some background details of your early life, when you began work in music? What were your beginnings in hip-hop all about? How and when did you start?

I was born in Detroit and came from a musical family. My great-grandfather on my mother’s side, Maurice King, was the Musical Director at Motown Records for ten years and that played a huge role in shaping the diversity of the music I was around as a child. I played violin and sung early, but I became entranced by hip-hop around the fourth grade. I was a big jazz head, so Illmatic (rapper Nas’ debut) was very instrumental in bridging the gap between my interests and hip-hop.

As I got older, I started producing and eventually working on a solo project as an emcee, and got serious about performing live. I struggled through a lot of open mics to find my voice, but things started clicking and a lot of that was being around a team of strong artists who helped sharpen my skills and give me an ability to showcase my talent.

You are from Detroit, probably best known for a lot of the house, techno and electro that came out in the ’80s. How would you describe Detroit’s hip-hop scene? How, do you think, it differs from the New York and L.A. scenes?

I absolutely love the Detroit hip-hop scene because of how many layers you can find in the music. The house/electro influence definitely sets our culture apart from the other scenes, but even with advent of Esham and acid rap — which in turn has heavy influence on an emcee like Eminem — we’ve always been innovators in the culture. There’s a reason why L.A. and New York are so heavily invested in the sound that Dilla created, and similar work with his protégés like Black Milk.

I often joke that Big Sean, on a mainstream level, has given the industry no less than four flows to steal from. Even a relative newcomer like Tee Grizzley, who embodies the street sound that’s heavy in Detroit, is influencing previously established artists to change some of their flow.

It’s a city with a rich musical history, spanning back to Motown, and I take pride in the fact that we find new ways to make music. There’s a smorgasbord here where everyone gets fed.

The 4th Wall is a continuation of an “inside joke” as you once put it, to your debut, The Final Season, a concept album of sorts (both titles being film/TV/stage drama references). Can you explain the concept behind both albums and what you did specifically with the themes on The 4th Wall?

A good friend of mine (who plays the role of the executive on both albums) and I were roommates for a few years, and around the time The Final Season came out, it seemed like that college/post-college period was coming to an end. We started recounting memories and that’s when I told him that year (2012) felt like “the final season”, like that period of time was one great TV show and it was finally time to move on.

True enough, shortly after that I moved to the East Coast for a few years (D.C. and Brooklyn) and it definitely felt like a shift from the golden era of my 20s. The main theme we presented in that first album was life, as I know it, with this idea that all these stories I saw play out in my life followed some narrative. It speaks a lot to my ideas on faith and fate, so I took real-life situations and tried to intertwine them into one drama.

The Minstrel Show by Little Brother definitely was an influence, and I love that album so I worked hard to make it clear that this was more of a “behind the scenes” explanation of the songs, presenting them as monologues. But the idea that life is like a variety show was definitely perfected by [Little Brother] first, so I followed that lead. I was in a really rough place mentally and emotionally when I made that album, and so the title also held the double meaning of potentially being my last record.

When I first started writing after that record, I stopped for about a year because my mood hadn’t changed and I didn’t want to create another of body of work so depressing. The early version of The 4th Wall wasn’t meant to be a direct sequel to the first album, but as things started picking up and I felt I could make a few more triumphant songs, I decided it would be proper to finish on a high note. I thought it would be a homage to popular shows like Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, etc., where we could say there would be a second part to The Final Season and finish it. There are a lot of Easter eggs, skits, and songs that reference the first record and I wanted to present that for the fans I do have, for sticking with me throughout the journey.

Your brand of hip-hop is interesting, considering that much of Detroit’s music scene (in terms of electronic music/dance/and a lot of hip-hop) is characterized by a minimalist but funky vibe. However, your hip-hop seems primarily bass-oriented, and explores a bottom-end heaviness. What can you say about this element in your work?

A lot of that is due to my producer Ryan “StewRAT” Stewart. We’ve been making music together over ten years now, and he’s very much into “groove”. The one thing I like in music is the ability to create a groove. I’m all for minimalist, but I feel best in my pocket when we can create melodies that can tap into the emotions of the people listening to the music. The bassline more or less serves as the heartbeat of music, so it makes it easier for me to literally function as the voice.

When I was making music earlier in my career, I was getting feedback that the songs were dope but needed more punch, so during the mastering process I’m big on maximizing the ability for the music to bang without there being distortion. With The 4th Wall specifically, I went to Studio One in Detroit, and Eric Morgeson, my engineer, did a great job of bringing the project to life. He’s a huge reason this album has more knock than any other that I put out before.

You were once offered a major-label deal at one point, earlier on in your career. However, you turned it down. What were the reasons and what do you feel about turning it down now? What are your thoughts about major-labels versus recording independently?

I was offered a developmental deal with Universal, where I would relocate to New York and make music under evaluation. It wasn’t a guaranteed deal, and since I was finishing up my senior year at Michigan State, I didn’t see the value in leaving for something that wasn’t concrete. I can’t say I regret the decision, but I often wonder what that would’ve been like.

I work at a school, not too far from MSU, and my students always say “you had a deal and you turned it down?!” and I use the analogy that to me it felt like leaving school early to play professional basketball in the D-League instead of the NBA. I see nothing wrong with chasing dreams and had I already graduated I likely would’ve taken that opportunity. But the decision I made is one I confidently live with.

I think ultimately majors and independents boil down to what resources you’re seeking. The thing I hate is that on both sides people are trying to laud one as inherently better than the other, usually to further an agenda. Being independent is hard work, but if you’re committed and have a fanbase with a few connections, the gain is greater. Even at this level, I can enjoy royalty checks and not having to give any of my guarantee up after a show. That helps me live comfortably outside of music. Majors do come with the benefit of the machine, and I think negotiating the right deal is totally fine.

In the past, you opened for Chance the Rapper. Of course, he’s gone stellar now, with Grammys and critically-lauded albums. What do you remember about opening up for him at that time?

Watching Chance’s rise has been a pleasure. First time I ever saw him was in 2013, when he was on tour near MSU with Kids These Days as an opener, and at that time he had this incredible buzz. He sold out the venue, which has a capacity of about 250, and I walked away from that thinking “this kid is going to be a star” and sure enough, when he came back to MSU two years later he was a bonafide star. And that was before Coloring Book and the Grammys!

The crazy thing about that show, is that the MSU Auditorium is a venue where a lot of notable artists like Big Sean and Lupe Fiasco had played before, but we never had. I offered my band to go first, under the deal that we could get a little bit more time than the other openers to set the mood. There was a confusion that night about when it was time for us to go on, and I felt that everyone — myself, the band, the sound engineers, and even the crowd — were getting a bit restless. I looked at the main sound engineer and we gave each other this mutual look as if to say “should we just go ahead and do this?” and with confidence I pretty much made the call. He dropped the house lights and the intro from our first song began to play.

Suddenly I hear 3,000 college students go crazy. I know they were hip enough to music shows to know that Chance wasn’t coming out first, so I felt good that they seemed pumped just to hear good music. That moment still gives me goosebumps.

As hip-hop becomes more and more evolved, you remain particularly Afrocentric in your work, closer to the material by Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces than most of what is going on now. How does this Afrocentrism keep evolving in your music as time goes on? What other influences has your music picked up along the way as you’ve progressed as an artist?

Afrocentrism is huge with me, and I feel it’s more important to stress my history given the abundance of stereotypes surrounding African-American culture. When I was going by my old stage name, JYoung The General, I linked up G-Unit producer Nick Speed in Detroit and we created two EPs called Black History Year. I felt it was important to teach some of the history of my ancestors and our experiences in America in a way that was digestible for today’s generation and people outside of our community.

The only drawback was I felt like I was eschewing my own personal narrative to serve as a hip-hop historian, so the Jahshua Smith records accurately reflect the place black history plays in my everyday life. I take a lot of cues from Nas who, at his best, has this ability to give a vivid depiction of the streets, have a few songs that you can ride to, and also have that higher understanding of who he is and where he comes from.

Over time I feel like a lot of the influences I put into the new music come from artists I know closely and also the region as a whole. Doing more ‘double time’ flows, singing a bit more (a talent I don’t exercise nearly enough), and even rhyme and verse structure all come from people I highly regard. Even my ‘hunh!’ ad-lib that I use often to start a verse comes from one of my former students. I pick up a little bit of influence from everyone who has a role in my life.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

I interviewed a rapper/lyricist some time back who once described his technique as a “medicine bag” of sorts; he had all kinds of flows that he could pull out, depending on what was needed at the given moment. How you describe your technique or delivery in your lyricism?

I like the medicine bag reference! I think my style builds on two consistent elements; multi-syllabic rhyme scheme and counter-rhythm.

In the earliest days of my rap career, one of my boys was helping me sharpen my vocabulary and he told me that he felt like my content was good but I needed to work on my flow. He taught me the value of rhyming multiple syllables (socially/vocally) versus just one (bat/cat) and it challenges me to not just craft lyrics that make sense, but also fit my rhyme scheme. That helps expand my vocabulary too. I listen to artists like AZ, Royce Da 5’9, and Raekwon who are masters at that and, much like them, I can’t say I pull it off 100 percent, but it’s hard to hear a single song of mine where that’s not a staple of my lyrics.

As for the counter-rhythm, emceeing turns you into another instrument. I like to play off the groove in a song — the bassline, kicks, snares, melody, or w/e — and find a pocket where I can give my lyrics musical value. Sometimes I’ll play it straight and stay in the pocket, but a lot of times I like to actively go against the grain so that the lyrics stand out and create another melody themselves. My favorite example of that is “Butt” off The Final Season, where I’m just playing off the vocal sample and the dance feel of the instrumental. I think it’s fun to play around with those sounds.