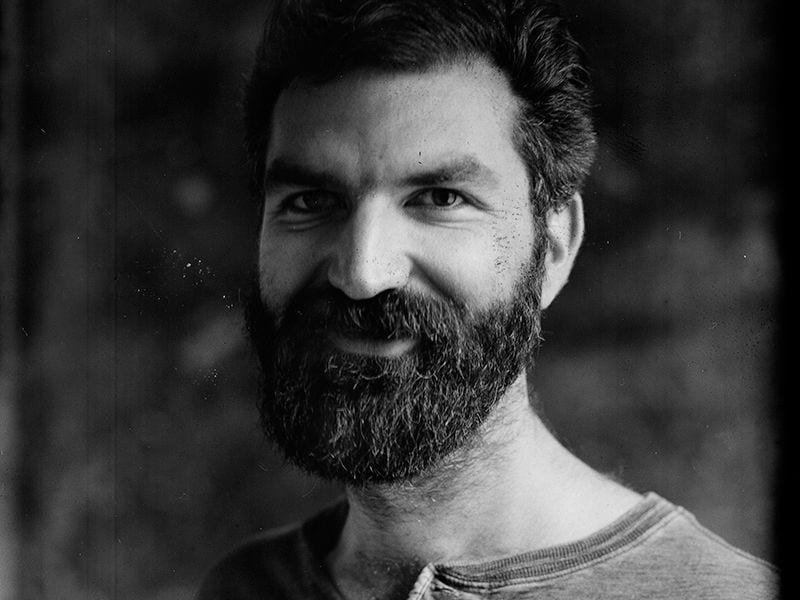

“Each film is a love affair” remarks director Jeremiah Zagar. “It’s like falling in love for the first time and then when you look back on the film, when you see the images, the moments that took place over the course of the movie, it reminds you of that love. I look at moments in the film and I remember an experience, a relationship that transformed my life.”

Zagar and co-writer Daniel Kitrosser‘s adaptation of Justin Torres‘ novel tells the story of three brothers against the backdrop of their parents’ volatile love, that both nurtures and threatens the family’s bond. Unlike his older siblings who are growing up to resemble their father (Raūl Castillo), Jonah (Evan Rosado) shows a greater sensitivity and consciousness, and protected by his mother (Sheila Vand) embraces an imagined world all his own.

This portrait of a working class family has an authentic sensibility of the continuous day to day struggles, but most notably offers a visceral image of the imperfect nature of family. It doesn’t surrender to an oversimplification of resolution, but instead looks to the struggle of enduring or surviving in spite of one’s imperfect self or life. Zagar’s narrative feature debut is less a retreat than a compliment to his documentary work that includes: Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart (2014), as well as Coney Island 1945 (2005), Paints on a Ceiling (2008) and In a Dream (2008) that are centred around his artist father, Isaiah Zagar,

In conversation with PopMatters, Zagar reflects on avoiding the easy answers to remain true to the spirit of the film he and his collaborators were intent on making. He also discusses the necessity of the unexpected to this spiritual drive of the film, and art has a connection to one’s younger self.

Why film as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

I loved movies when I was young and I still love movies, but when I was a kid I went to the movies all the time. I wasn’t a popular kid, I was a little bit heavy and husky as they say, and being dyslexic, I was really bad. I was on the verge of failing out constantly, but I loved the movies and my parents saw that, and so they fostered that in me. They got me tickets to the movies — I could go all weekend long and rent as many movies as I wanted from our video store, which I did.

So when I was a kid I wanted to be a video store clerk; that’s what I wanted to do with my life. I actually got a job at the video store as a clerk, but they fired me weeks later, and so I realised I was never going to be a video store clerk [laughs]. It was a bad career path and so I reeducated myself to making movies, to being the director… You know, it’s harder to fire the director.

Film is such a collaborative art form, and the idea that a film can be by one person or just two undermines this collaboration. Do you believe the auteur theory is valid, or is it a theory that if valid, needs to be revised?

Yeah, like you said I think it’s bullshit. The director is an important piece in the puzzle of collaboration that makes up a film, but everyone, by playing a different role, is valuable in different ways. I don’t want to make films where I’m the only voice involved, I think that’s crazy. It was vital to me that Justin [Torres] was creatively involved in the movie, and we were never making something that he couldn’t be proud of.

It was the same with my co-writer Dan Kitrosser, for my editors and for the producers. When you create an environment that everyone feels they are creating together, you get a much better product because you can feel the pulse. What We the Animals had was a kind of universal pulsating energy and that’s based on a lot of people’s pulsating energies combined by working together. The director’s job… is to make sure that energy is all working towards the goal.

There’s a perspective amongst filmmakers that there are three versions of the script – the script that is written, the script that is shot and the script that is edited. Did you end up with the film you imagined in your mind at the outset, or was the film a journey of discovery?

Yes and no. So yes, this is the film we set out to make, there’s no doubt. But is it the film we wrote? It’s definitely not, and it’s not the film that we shot, but it’s definitely the film that we cut. I’m sure the audience will take something away from it whoever they are, and if we ‘re lucky enough, will bring life to it. But it’s the spirit that’s important and a lot of this has to do with my documentary background.

When we make documentaries we have an idea of what the story is, but we are open to the flexibility of change. That’s what’s thrilling about documentary, how in the moment and then in the editing anything is possible. So we followed that ethos when making [We the Animals]. Justin’s book and our script was the map, and when we got to the places where we wanted to veer off that path, we were allowed to.

A part of what feels so alive about the movie is that it veers into places that are unexpected — even for us. The key is just making sure you reign the movie into its core, so that in the editing you’re constantly going back to the heart of what the film is about in every shot and in every scene. In that way, the movie is the heart of the book and I really feel we are true to it. But the movie became an organic living thing that definitely changed from what was expected.

On the subject of what’s expected, the film refuses to allow an incident of domestic violence to evolve it into the story of a family falling apart. While this scene brings a more visceral resonance to the juxtaposition of a loving yet violent and volatile family, it more importantly seeks to depict the complexity of life and our feelings, and the unconditional love of this one family.

Yeah, the key for us was that love and life are messy and complicated. I think often in narrative they are simplified into flat, boring, and unrealistic ideas of good and bad, of monsters, princes and kings. To a certain extent they are Disneyfied, and we just didn’t want to do that.

What I loved about Justin’s book was that it was like my family: nuanced, dirty and real, and there were never easy solutions to anything, and there were never any easy scapegoats either. There was a mother and a father who weren’t perfect and three children who were far from perfect, and they had this deep love for each other. We wanted to communicate that kind of love, and that’s what the movie was about for us; how there are no easy answers because love is not easy.

When I think about the performances, the cast express themselves as much through silent expression as they do verbal. The way in which the camera frames the actors allows us to just gaze upon and study them, encouraging us to look more closely that empowers us as an audience.

To be honest, the desire to have the characters speak without speaking is something that I felt in films that were enormously influential on me – the socialist realist films from the UK, and the films of Ken Loach. When I first saw Ratcatcher (1999), Lynne Ramsay was accomplishing so much simply by where she placed the camera in proximity to the people in the film. So I started to think about how frame can be so important in cinema, that you can see your movie as a series of images and indelible imprints, and your characters can become a part of those. I’m a huge fan of documentary photography and so we very much wanted this film to feel like a series of photographs that you could almost put up on the wall; images and moments that these characters are experiencing, without needing to tell you exactly what they are saying or thinking.

Our spiritual sense of self can be beautifully captured through art and philosophy, and here, Jonah detaches from this physical sense of self by way of a spirituality that comes through in his drawings, thoughts and imagination. The spiritual is freer and more flexible than the physical, and We The Animals explores this divide that each of us has through the character of Jonah.

When you’re young you’re able to use your animation to elevate your sense of being. So you have an incredibly tangible experience with the world, and yet you’re very easily able to transform that experience into something spiritual. In other words, children can get in touch with a dream while awake faster and more easily than we can as we get older.

What I love about making movies and what Justin loves about writing books is, I haven’t talked to him about this, but I think it allows us to get in touch with that side of ourselves that we knew when we were young — that easy way of transcending our physical world. And so, in the dreams that we create now, we can somehow connect to the experience we were able to experience when we were young.

Part of what I love about this movie is that it takes you back to that time when you were that young man or that young woman who could create something out of nothing, something spiritual, something tangible. I have a three year old son and I watch how easily he plays and how easily he disappears into a world all his own, and I am jealous [laughs]. I wish I could do that as quickly and as joyfully as he can.

Filmmaker Christoph Behl remarked to me: “You are evolving, and after the film, you are not the same person as you were before.” Do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect to the creative process, and should the experience of watching a film offer the audience a transformative experience?

Well I don’t think so much about the audience after I make the movie. Once the movie’s done, I sort of feel like the audience will do with it whatever they will, and you hope they find it transformative. But certainly for me, who I am now is a very different person from when I began this movie. A lot has happened and a part of that is just life. In the process of making this film my wife and I had a child, who’s in the movie. I met all these people that are in the movie, who are all my close friends, and there were more people I collaborated with. So you build a community, too, and that enables you to grow and change.

I make short films and it doesn’t always happen, but one thing that happened in this film is that we made something that was transformative for ourselves. We went into the experience trying actively to transform, not trying to create something like I said when we began this conversation that was on the page. In the same way that we were open to the transformation of the film, we were open to the transformation of ourselves. And of course every single person involved has transformed, not just me because it was like being in a crazy commune that at some point had to explode. I couldn’t tell you exactly how we’ve changed, I just know that it’s true, that it happened.