The Searchers asks, What makes a man to wander?

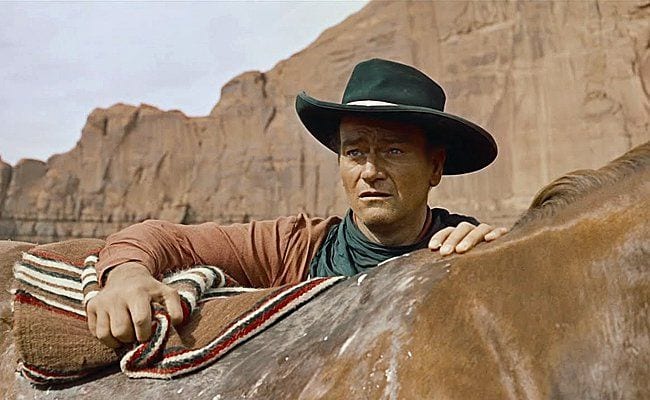

Steve Pick: We come to the first Western in our series, the John Ford masterpiece The Searchers. I say “masterpiece” because few films are so tightly focused, beautifully filmed, and aware of ambiguities. From that wonderful opening shot through the door of the small home out on the Texas prairie to the final shot through another door, as John Wayne saunters away from family, friends, and purpose, this movie takes away breath so often it should come with an inhaler.

Yet, there are issues to discuss, not the least of which include the treatment of Native Americans, questions of cultural identity, the meaning of the word “family”, and the general concept of the “hero” in American films. The Searchers exists in the context of hundreds of other Westerns, not to mention thousands of dime novels, pulps, and paperbacks. While delivering the thrills inherent in the genre, it seems that The Searchers does not take its tropes for granted but digs deeper into their meaning than we are used to seeing.

So, Steve, I’ll let you start by asking your take on John Ford’s The Searchers in general and, more specifically, your opinion of John Wayne’s character in the context of the film.

Steve Leftridge: You introduce enough topics in your opening paragraph to fill Monument Valley, Utah. I’ll start by acknowledging that, for all of The Searchers‘s considerable acclaim and influence on other filmmakers, it remains one classic that some viewers resist and consider vastly overrated.

I don’t share such a view, finding the film psychologically rich and gorgeous to look at. I once engaged in a thundering debate with a good friend over the merits of John Ford’s The Searchers, during which we said unforgivable things to each other. He contends The Searchers is packed with ridiculously dated stereotypes, clumsy acting, goofy dialogue, and unintentional campy humor.

Yes, we’ll get to some of that, but my argument remains that the film’s rewards far outweigh those concerns. (The novelist Jonathan Lethem wrote about this common Searchers debate in his essay “Defending The Searchers“.(

As for John Wayne’s character, he is a huge part of what makes the story so fascinating to watch unfold. As Ethan Edwards, Wayne is such a mountain of a man, the quintessential American archetype: tough, ruggedly self-sufficient, physically skilled, and driven by his values and codes of behavior. Ethan is in many ways a classic American hero, but his anti-heroic qualities are just as conspicuous, not the least of which is that his burning racism knows no bounds.

This leads me to my question for you, partner. Clearly, the audience is not supposed to sympathize with Ethan’s most heinous anti-Native American behaviors, from which the other characters (and we as the audience) recoil. On the other hand, perhaps John Ford let a few racist elements remain in the film. So, in what way(s) do you think The Searchers is a film about racism, and in what way(s) is John Ford’s The Searchers itself still a racist film?

Pick: Well, the most obvious point of racism is one common to all too many Western films, which is the fact that the actor playing Scar, the Comanche who kills John Wayne’s brother and family and kidnaps Debbie (Natalie Wood), is played by a German actor, Henry Brandon, and not a Native American actor. Since many of the extras in the scenes with Comanches are Native Americans, Scar stands out in ways that detract from the film’s veracity. As I said, it was common for Westerns to use white actors to portray Native Americans, but there is nothing Brandon brings to the character that justifies it in this case.

In addition, it’s way too easy to root for the white people in the climactic battle scene. Ford films it from the point of view of John Wayne and the army, and he includes stirring music that is so familiar from many other heroic sequences in previous films. I didn’t see The Searchers when I was a kid growing up in the early 1960s, but those kinds of fight scenes were common in Westerns on TV in those days, when it never occurred to us to consider the point of view of the people who were fighting against the whites.

But Ford tries to subvert the standard story. We are told that Scar carries out at least some of the killings in retaliation for the killings his people have received. We are shown that both sides perform heinous acts on the other. Ford also shows multiple perspectives within the white community; Ethan and Martin (played by Jeffrey Hunter) have different plans for dealing with “rescuing” Debbie.

For that matter, though Ford chickens out at the end and lets Debbie make an unearned return to her white roots, she is allowed to desire to stay with Scar in several scenes. I’m sure there is no way The Searchers would have been successful if Wayne had killed her as he had said he would, but that was the inexorable pull of the way these characters were.

Or am I missing something? What was your take on the character of Debbie Edwards, and the questions she raises about cultural nature vs cultural nurture?

Leftridge: I think ohn Ford makes several attempts to adjust the good cowboy versus the bad Indian archetypes of earlier Westerns, mainly by showing Ethan, the film’s worst racist, being such a jerk. There is no way that Ford intends for the audience to agree with Ethan when he commits his most offensive acts of racism: firing his rifle at the Comanche as they retreat and clear their injured, indiscriminately killing buffalo to provide one fewer meal for a Native American that winter, and shooting the eyes out of the dead Native American so that he’s blind in his afterlife.

It’s one thing to ruin a man’s life on earth; it’s another to attempt to screw up his eternal life in the great beyond as well. “What good did that do you?” Captain Clayton asks Ethan, and we reject Ethan’s ugliest tendencies, such as his hostility to Martin for having even a small percentage of Native American blood.

Conversely, Martin might be the most sympathetic character in John Ford’s The Searchers. Unlike Ethan, Martin wants to save Debbie, not kill her, and he collapses in anguish when he is forced to fire upon Native Americans during the firefight across the river. So Ford depicts the film’s anti-hero as a ferocious racist and the film’s nicest guy as an anti-racist. Furthermore, Ford shows us Comanche mothers grabbing their children and scrambling for safety as the Cavalry rides in to lay waste to their village. Clearly, we aren’t meant to applaud such action.

On the other hand, there are times when Ford slips, including, as you mention, the blue-eyed white man who plays Scar. But you asked about Debbie, and I think it’s with young girls that Ford tends to reveal still-existing racist notions. For example, how about that scene when Ethan and Martin come across two young girls who have been recovered after living for years with Native Americans? Those girls have gone completely bonkers, screaming gibberish and laughing maniacally at jangling keys. “It’s hard to believe they’re white”, the officer says. This is what happens when white girls live with Native Americans for a while?

Then there’s Look, the Native American girl whom Martin inadvertently “marries” during a bartering session. At one point, Look dutifully tries to lie down next to Martin’s sleeping bag for the night. When he discovers this attempt at matrimonial closeness, he kicks her very hard with both feet, sending her rolling down a hill. What’s most amazing about this scene is that it’s totally played for laughs, with comical, cartoonish music and broad laughter all around. Sure, it’s a sexist sequence, but it’s more racist than anything. Had it been a white woman lying next to Martin, there’s no way Ford would’ve shown Martin exact such violence against her and expect audiences to find it funny.

Pick: I think you’re right, and I think you’ve hit upon the limits of the “progressive” viewpoint circa 1956. Ford was willing to accept that Native Americans were human beings, but he couldn’t shake the deeply-embedded racism that made poor Look an object of derision.

You described Ethan as an anti-hero, yet in so many ways, he upholds conventional heroic attributes. You certainly can’t question his courage, his strategic wisdom, and his conviction in regards to fulfilling his heroic quest. Ethan is more rigorous in his hatred of Native Americans than the other characters, but a cursory look at American history books will show that his attitudes were more common than those of Martin, for example. It may be that the quest itself is the anti-heroic act. Heroes may seek revenge, but only as a secondary function of performing acts of good.

If we disallow the ways Debbie is shown to have acclimated to Native American life, there is a clear wrong in her being kidnapped. Her sister was presumably raped and murdered by the same people that took Debbie, and it is understandable that those left behind would want to perform a miraculous rescue. That Ethan and Martin stay so true to their quest for so long is clearly meant to be admirable, though it is clear that Ethan believes the endgame will require him to kill Debbie since she has lost her white identity.

As I mentioned, I think Ford chickened out in having Debbie suddenly renounce her allegiance to Scar, though I suppose by the time she did so, it was pretty much a matter of realpolitik. It’s not as though her Comanche protector is still around to give her any kind of life, so she might as well go back to what tenuous roots she has left in the white world. Martin thinks of her as his sister, since he was raised by her parents, but other than that, the only family she has left alive is Ethan, who walks away at the end of the film with no connection to keep him in her life.

Ford, perhaps inadvertently, raises interesting questions about the mutability of culture, and the meaning of family itself. Is family blood? If so, that explains Ethan’s determination to avenge his brother, and “rescue” his niece. Or is family those you love and live with? If so, that explains Debbie’s willingness to stay with Scar, who managed to make her comfortable in her new life, despite its terrible beginning. It also explains Martin’s determination to get her out alive and restore what’s left of the life he lost.

Leftridge: Debbie seems like little more than a vehicle for Ethan to act on (or be redeemed from) his own psychological burdens. Ethan was obviously in a relationship with Martha, his brother’s wife, before the war. (I love that scene near the beginning when Captain Clayton pretends he’s not there as he finishes his coffee to allow Ethan and Martha to have a brief moment together.) In this sense, Scar has done what Ethan most desires to do: invade his brother’s home and have sex with Martha.

In fact, for all of Ethan’s hatred of the Comanche, he has a lot in common with them and with Scar in particular. Tellingly, once Ethan finally meets Scar, they stand face to face, mirror images of each other, repeating the same lines to each other (“You speak good American/Comanche—someone teach you?”). Ultimately, they are driven by the same motivation, revenge, and Ethan even turns Scar’s own methodology onto him when Ethan scalps him at the end of the film.

This ritualistic destruction of the appropriately named Scar is actually a way for Ethan to exorcise his own unacceptable psychosexual desires, which are revealed at various points, like when Ethan plunges his knife into the ground over and over after discovering Lucy’s raped and murdered body. So Ethan can only accept Debbie (holding her high in the air as he did when she was younger, another of the film’s many parallel shots and double images) once he has mutilated Scar. Or, more revealing, Ethan can only allow Debbie to live after learning to accept Martin (he “bequeaths” Martin his property), thereby reaching some peace from the vitriolic hatred that consumes him.

However, your point that there is no lasting retribution for Ethan is a good one. He remains an outsider, not much different from the scene at the beginning when Aaron is taking Martha to bed while Ethan is relegated to the porch outside with the damned old dog. In fact, Ethan is such an antisocial figure that we see him disrupt the two ceremonies during which people tend to be on their best behavior—a funeral (“Put an amen to it!”) and a wedding. When Ethan shows up at the wedding, the bar goes from closed to open and the dancing is replaced by fighting.

Therefore, in the end, with Debbie returned to the homestead to live with the Jorgensens, Ethan can only look in from outside and then turn slowly away from family and community and drift off alone. What makes a man to wander? We leave this Double Take with the same question that haunts the end of this great film.