Reading the English translation of Julie Delporte‘s This Woman’s Work makes me wish I could read it again in its original French—not for any imagined flaw in its translators’ fluid prose (Helge Dascher and Aleshia Jensen), but the opposite: I would like to understand this intensely personal, affective memoir existing in it original iteration.

No translation is simple. Every language has not only its own sounds, but no two words share exactly the same set of connotations, even when their dictionary definitions appear identical. Sometimes differences are overt, as when Delporte declares: “the grammar I was taught still hurts,” she must add an explanation in an asterisked note at the bottom of the page: “In French, the masculine takes precedence.”

Graphic novels add another level of complexity because a choice of font—something readers of prose-only novels hardly register—is a visual element embedded into each page. Translating the effects of graphic design is even more complicated when the words aren’t contained by talk balloons and caption boxes of conventional comics. Delporte’s words are all unframed. Her script winds around and between and sometimes overtop her drawings in similarly penciled lines, dissolving the differences between handwriting and drawing style, diary and sketchbook. Few comics are composed of more thoroughly integrated image-texts, a form well-suited to this single-author memoir.

Whether composing letters or images, all of Delporte’s lines are evocative, each color carefully chosen. When she depicts herself having sex with a lover in an attempt to become pregnant, her drawn self exists only in blue pencil and he all in orange, their lines almost but never quite touching. When she lists the promises she wishes he had said to her afterwards, most expectant mothers would probably like to “hear” the three she scripts in blue: I’ll take care of her, change the diapers, nurse her. But Delporte pencils the most important unsaid assurance in orange: “You’ll be able to draw.”

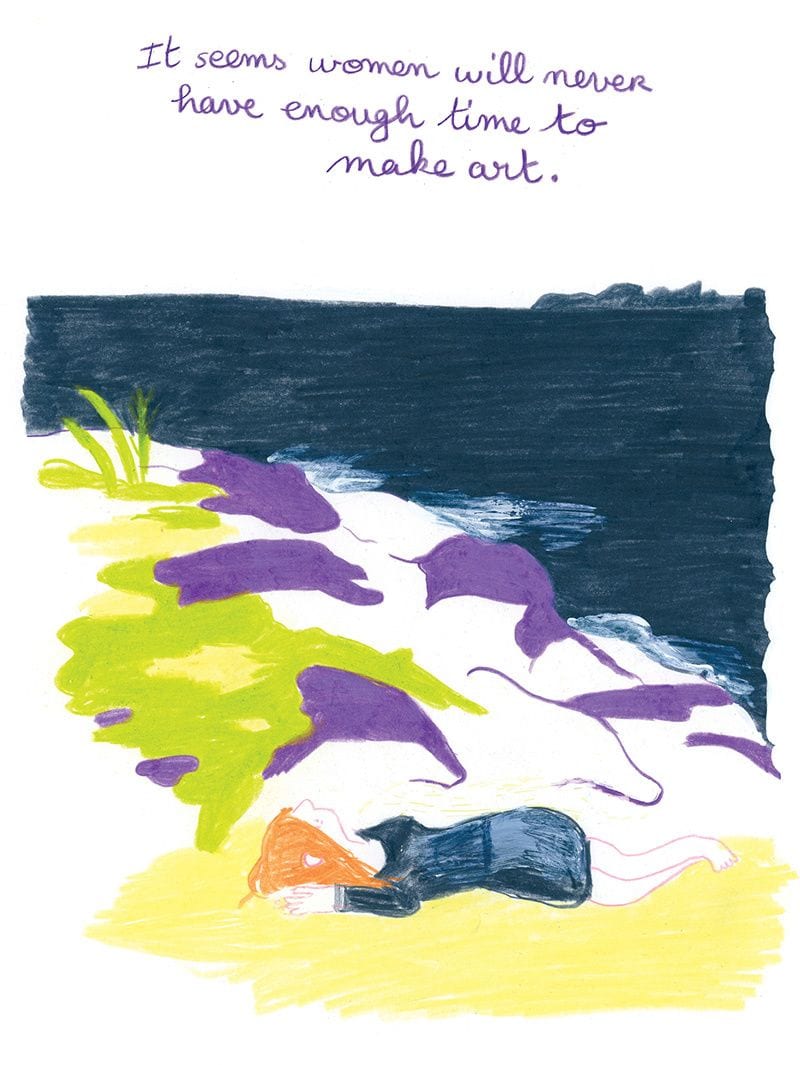

Indeed, Delporte is a female artist documenting her private and professional search for her own place in a male-dominated field and world. The search is life-long and takes her on a non-linear path around Europe and North America and deep into her own past. She fills her novel with personal reproductions of works by female artists, each linked to critical moments in her own life. When she imagines having to raise a child on her own, she sketches a Mary Cassatt painting of a mother holding a child, giving the image a double meaning, since it both represents her possible self and the artistic lineage she is constructing.

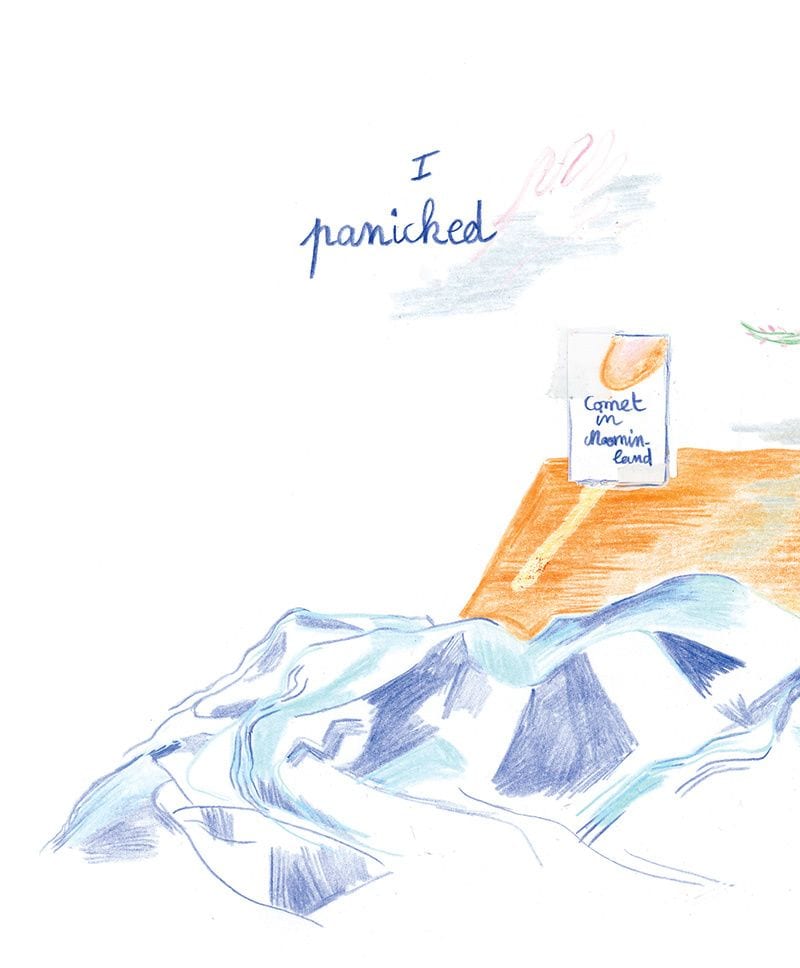

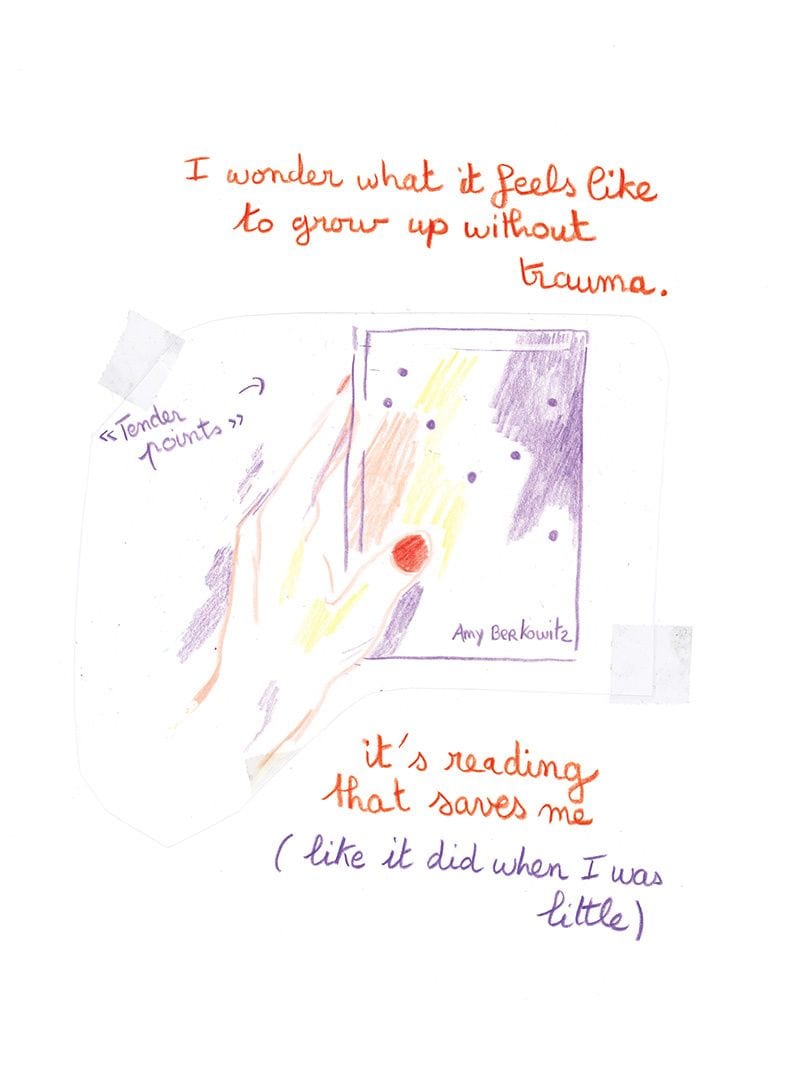

Delporte travels to Finland to write about Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins, cartoon trolls who are “happy idiots who forgive one another and never realize they’re being fooled.” That description is Tove’s, but for Delporte it encapsulates the role of women. She claims she’d “give almost anything to be like” the Moomins, but her memoir is her struggle to escape that past—including the darkest moments of her childhood. She received her “first lesson in sex” by a slightly older cousin, but when she later dreams about the trauma, it’s not the event but how the adults in her family never responded, never spoke about it. Now she looks at her family tree and wonders, “which of these women were raped?”

That central trauma permeates but does not define Delporte’s work. The memoir is much more of an attempt to construct something new, even if it is necessarily incomplete and tentative as she wanders between continents and decades of memories. When she grows frustrated with writing and drawing, she turns to ceramics for something more tangible. The pages of her memoir have a similarly tangible aesthetic. The ghostly edges of transparent tape seem to hold the scissors-cut images in place. Some words are written on strips of paper, their near-whiteness almost but not quite matching the white of the book’s actual paper. Several pages are reproductions of her sketchbooks, their bent corners creating a book-within-a-book illusion.

Some of her images are precisely finished, while others seem gestural and preliminary, faces left blank within the frame of a head. That incompleteness is essential to the larger project, as when she describes herself “struggling to draw” her own vagina because she “lived so long without an image of one.” She sketches the character Rey from Star Wars for the same reason, delighted to see “a self-sufficient woman, on the screen.” When she was growing up, she only had Wynona Ryder playing Jo in Little Women, a character who marries an older, more accomplished man—the plot closure Delporte now rejects.

She also varies her layout style, creating a cramped intensity for pages relating her physical travels, but rendering certain memories and dreams more sparsely. Her hand-written script grows in size too, with only a few words filling an entire page, often juxtaposed against a single image on the facing page. The switching styles give the memoir a visual rhythm, while also accenting the literally larger-than-real-life content. Delporte dreams of magically appearing babies, and strange bristles growing from her legs, and stabbing a polar bear in the heart to save her own life—each a bright fragment in the not-yet-complete puzzle of her search.

It’s fitting that this French memoir ends with a dream sequence situated around an untranslated term. A community of female poets live in a “béguinage”, a building complex for religious lay women who don’t take the vows of nuns. Though Delporte earlier glossed the male-dominance of French grammar for English-only readers such as myself, here she appropriately leaves us to find a dictionary ourselves. But this utopic vision, where women work together making art and raising children who venture out into the world when ready, ends on a far more ambiguous note: a page seemingly torn from Delporte’s sketchbook diary as she draws herself in bed while her lover sleeps downstairs because they’ve just fought. She writes: “I’m scared to death I’m pregnant.”

That poignantly open-ended conclusion seems the best closure possible for a memoirist still struggling to make her life work.