The average professor spends the summer revising syllabi, planning future courses, maybe teaching a summer class or two. With some luck, there’s time for a vacation. Artist and MOMA poet laureate Kenneth Goldsmith most recently spent his carrying out a conceptual art piece that entailed printing out the entire Internet — or as much of it that fans and admirers mailed from around the world to his 500 square-meter art space in Mexico City. That includes everything that appears, or has appeared, anywhere on the Internet — Facebook photos, news articles, pornography, dating profiles, and literally anything else.

We spoke with Goldsmith via email about the impetus for the entirely unprecedented exhibit and how it looked in practice.

How (or when) did you first conceive of the idea to print the Internet?

When Pamela Echeverria asked me to curate a show at LABOR in memory of [late programmer and Internet activist] Aaron Swartz, my mind naturally went to immensity. What would the web look like if it were somehow materialized?

I began by seeking works that explicitly deal with concretizing the digital. For instance, I wanted to show a huge book that consisted of every photograph of Natalie Portman on the Internet. Things really began to jell when I discovered a piece by an Iraqi-American artist, which was a collection of every article published on the Internet about the Iraq War, bound into a set of 72 books; each book was a thousand pages long.

Displayed on tables, they made a stunning materialization of the quantity of digital culture. But somehow these gestures — although immense — were not enough. They were too precious, too boutique, too small, to get at the Swartz-like magnitude of huge data sets that I was seeking to replicate. Inspired by these works, I wondered how I could up the ante on those gestures. They showed that printing out even a small corner of the Internet is an insane proposition: What if we were somehow able to print out the whole thing?

When did you decide to seriously pursue this?

On May 22nd, we put out the call on the web. Thanks to the wonders of social networking, I spread the word: “UbuWeb, Kenneth Goldsmith, and LABOR invite you to participate in the first-ever crowd-sourced attempt to print the ENTIRE INTERNET.”

How has the exhibition proceeded? Any unexpected challenges or pleasant surprises?

More than 20,000 people from all corners of the earth have thus far contributed. We have over ten tons of Internet in the gallery. The response has been overwhelming.

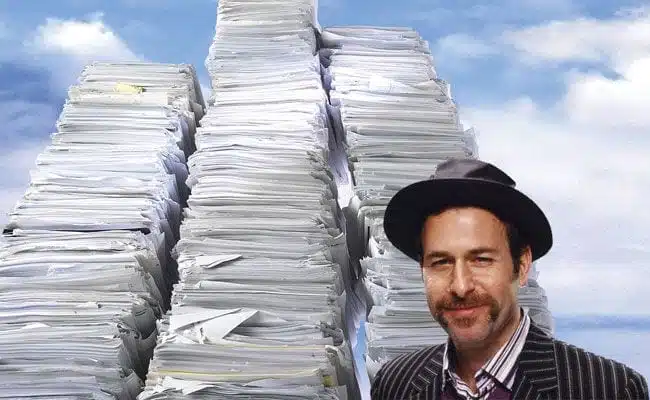

The materialization of the web is a wonder. It’s a giant pile of paper, six meters high, taking up many square meters of space. In a separate part of the gallery are long tables of examples that people can peruse close up. There is also a table and a microphone with a stack of Internet, which people are constantly reading from.

How does this project relate to Aaron Swartz?

The show is inspired by Swartz, but instead of making point-to-point correspondences, it is a poetical, or “pataphysical”, interpretation of Swartz’s actions. Like much of the world, I’m impressed by the largess of his vision and idealism, and like many others, I was devastated by his fate. Aaron Swartz’s gesture was a conceptual one, focused around the power of making available sealed-off information. He wasn’t concerned with what he was liberating; he was interested in using the model of moving information as a political tool.

The Swartz liberation enacts an evacuation of content as a political act, as if to say that the gesture of furiously pushing, moving, gathering, sharing, parsing, storing, and liberating information is more important that what’s actually being moved. Swartz was a liberator of imprisoned artifacts, freeing in bulk what should, by his reckoning, be available to the public. We wanted to demonstrate this in very material terms in the gallery space.

What is the most committed opposition or criticism that Printing the Internet has evoked?

It’s been mostly concerned around the prospect of an arboreal holocaust. But paper companies are not clear-cutting national forests to make paper; most use trees planted for that express purpose of making paper, and after harvest they plant more trees. And the whole show will be recycled at the end, so it’s an environmentally happy situation.

How have you responded to your critics?

I like to retweet or reblog their criticisms. After all, this project is a conceptual one, and in conceptual art, the conversation about the art is often more interesting than the art itself. The fact that even such a proposition, conceptually speaking, would set off a fierce global conversation tells me that it’s really hit a cultural nerve, thus making the entire project a great success.

What connection, if any, do you see between Printing Out the Internet and your own poetry?

My own writing has long been concerned with concretizing ephemeral immensity. I’ve published books consisting of every move my body made over the course of a day, every word I spoke over the course of a week, a transcription of a daily newspaper that was published as a 900-page book, a years’ worth of weather reports, 24-hours’ worth of traffic reports, and so forth. I once ended one of my books with the moniker:

IF EVERY WORD SPOKEN IN NEW YORK CITY DAILY WERE SOMEHOW TO MATERIALIZE AS A SNOWFLAKE,

EACH DAY THERE WOULD BE A BLIZZARD.

We’re swimming in a digital ocean of vast proportions — this might begin to make us aware of its magnitude. With an unprecedented amount of available text, our problem is not needing to write more of it; instead, we must learn to negotiate the vast quantity that exists.

I’ve said that archiving is the new folk art, something that is widely practiced and has unconsciously become integrated into a great many people’s lives, potentially transforming a necessity into a work of art. The advent of digital culture has turned each one of us into an unwitting archivist. We have more, say, MP3s on our hard drives than we’ll ever be able to listen to in the next ten lifetimes, yet we keep on downloading more.

I think it’s fair to say that most of us spend more time organizing and managing our cultural artifacts that we do actually interacting with them. This is a new condition, something that the concept of this show wishes to underscore.

You invited people around the world to send you print-outs of the Internet. What is the strangest or most memorable item you received?

Somebody actually printed out all 6,325 pages of YouPorn and sent it to us. That might’ve been my very favorite.

Have you rejected any submissions?

No. If it exists on the web, it’s included. And everyone who sends something in — if they are an artist — can put on their resume that they have participated in a group show in Mexico City’s best young gallery. I’m opposed to art world elitism and exclusion. My project is inclusive and open to all.

Why Mexico City?

LABOR is the very best young gallery in Mexico City. It’s an enormous space with a global reputation, known for its adventurous and cutting-edge program. I’m honored to be curating this show there.

Were you surprised or pleased by the media reactions to Printing Out the Internet?

The world has been captivated by this. Vast media outlets in every country have run stories about it: wire services have picked it up; we’ve gotten huge radio coverage.

But what makes me the happiest is that Printing Out The Internet received its own page on Know Your Meme. That reason alone — the fact that this has become an official meme — validates everything I’d hoped to accomplish with this show.