Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s powerful graphic novel Grass could not have hit the shelves at a more timely moment.

Originally published in South Korea in 2017,

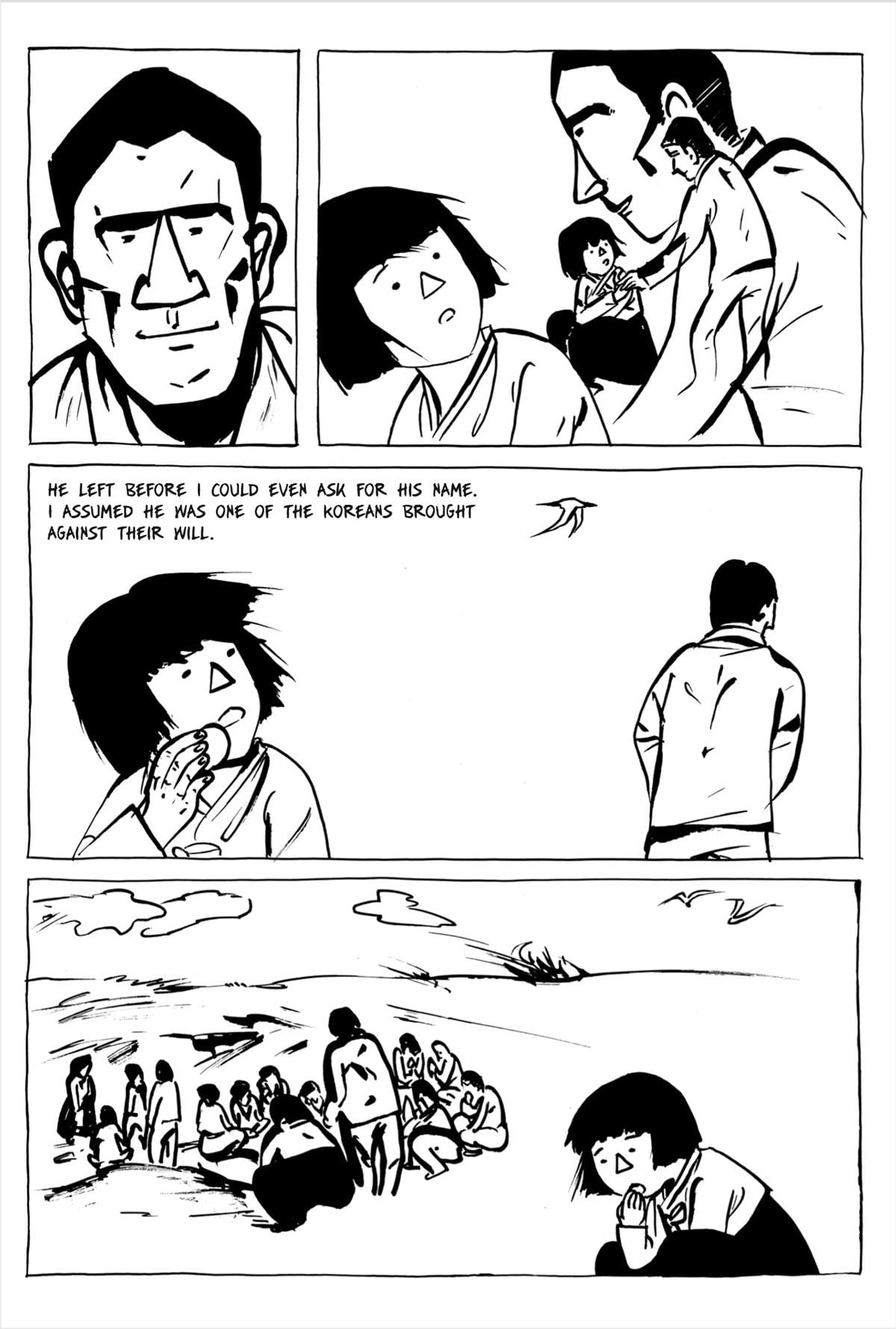

Janet Hong‘s English-language translation for Drawn & Quarterly came out in the summer of 2019. It tells the story of Korean comfort women – a term “widely used to refer to the victims of Japanese sexual slavery,” the author explains. Gendry-Kim’s vantage into this experience comes from Granny Lee Ok-sun, a survivor who shares her life story with the author.

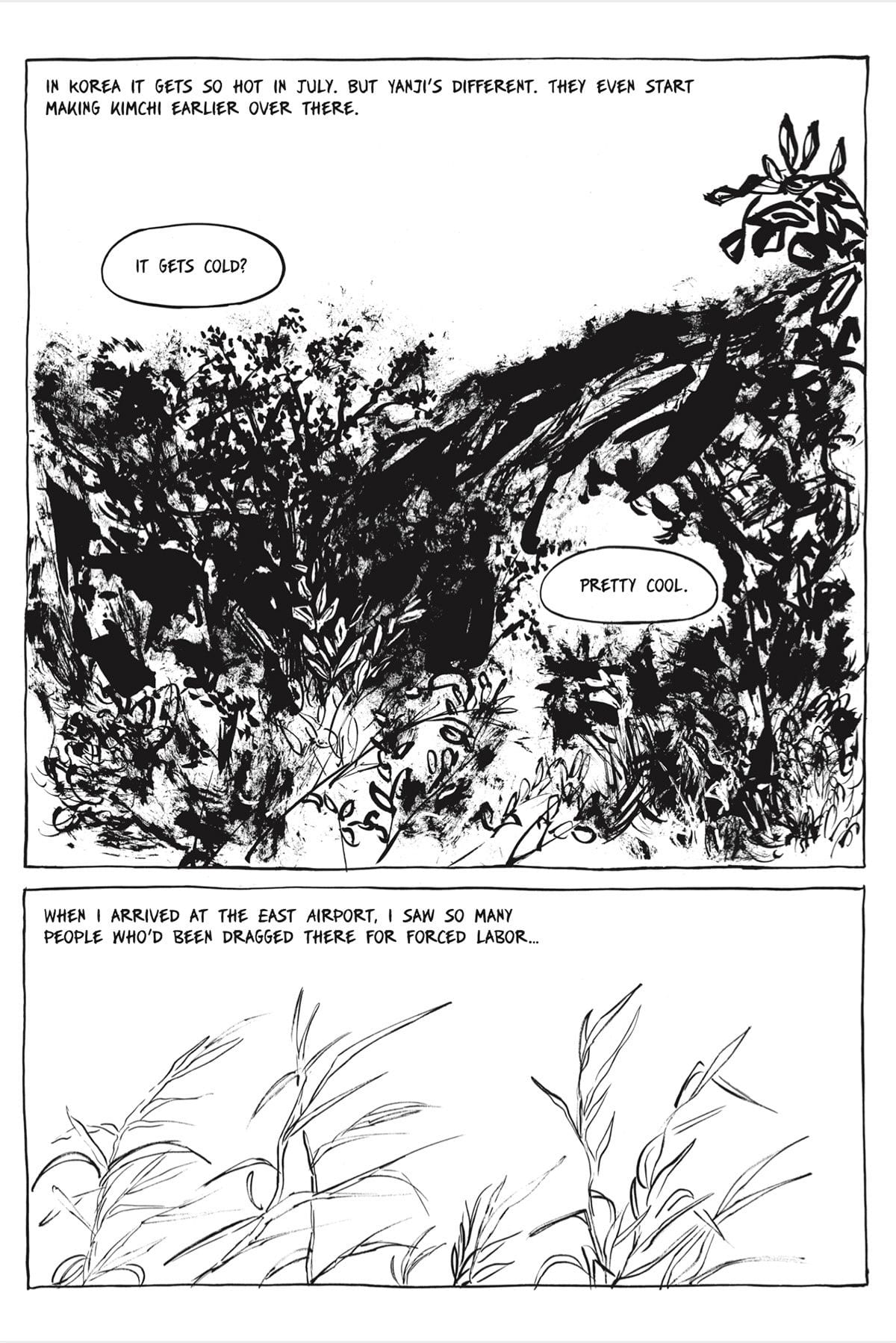

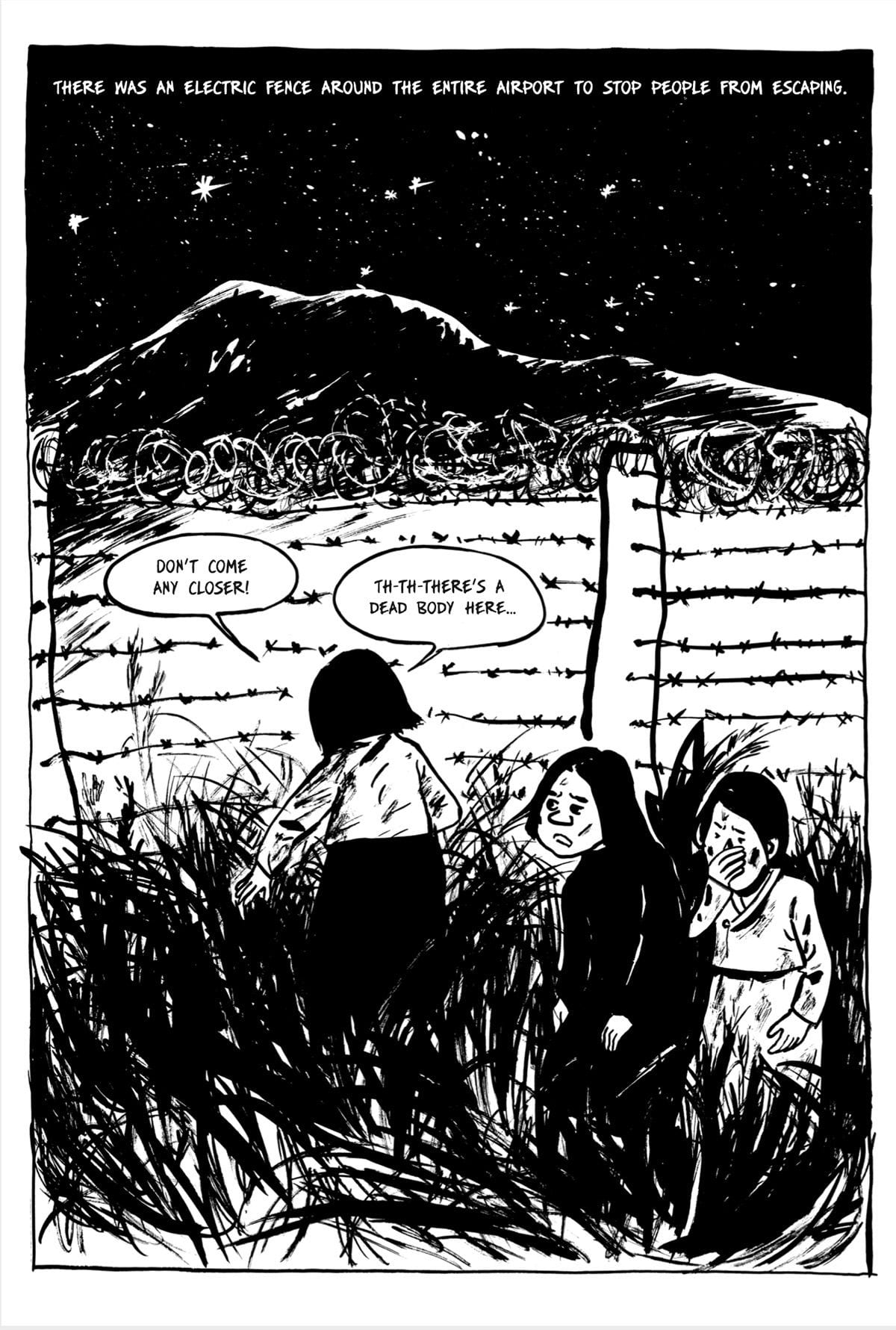

The artwork in

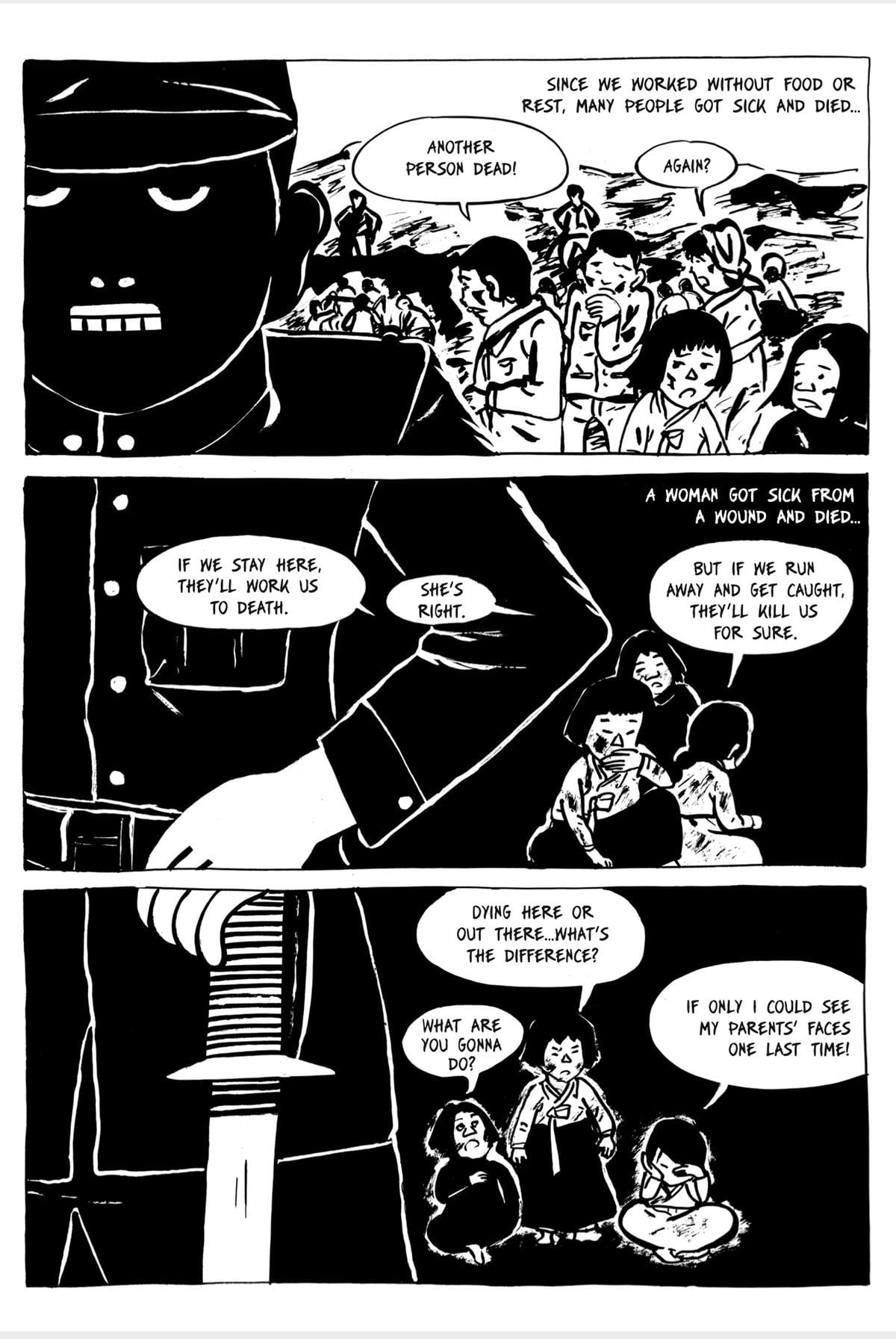

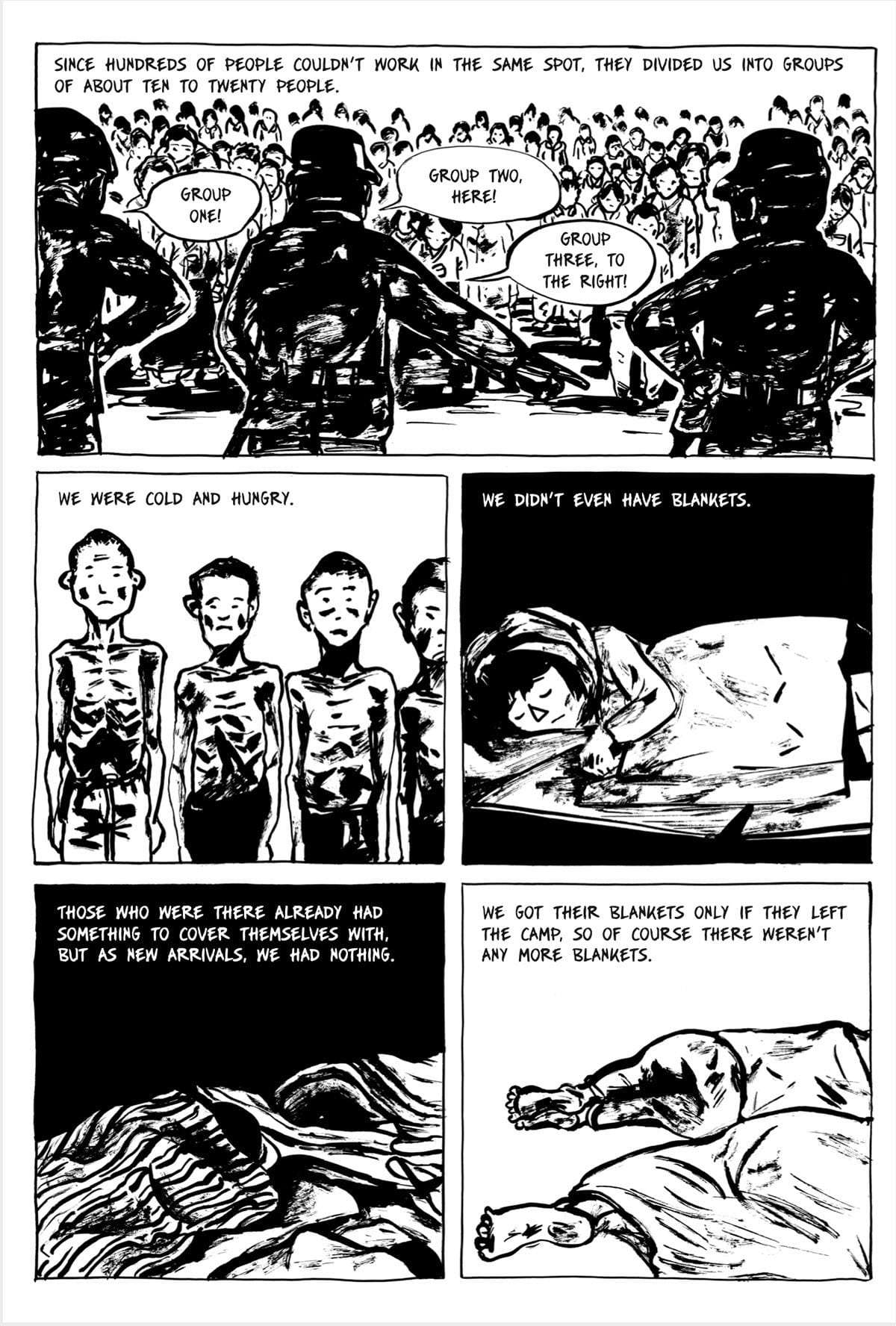

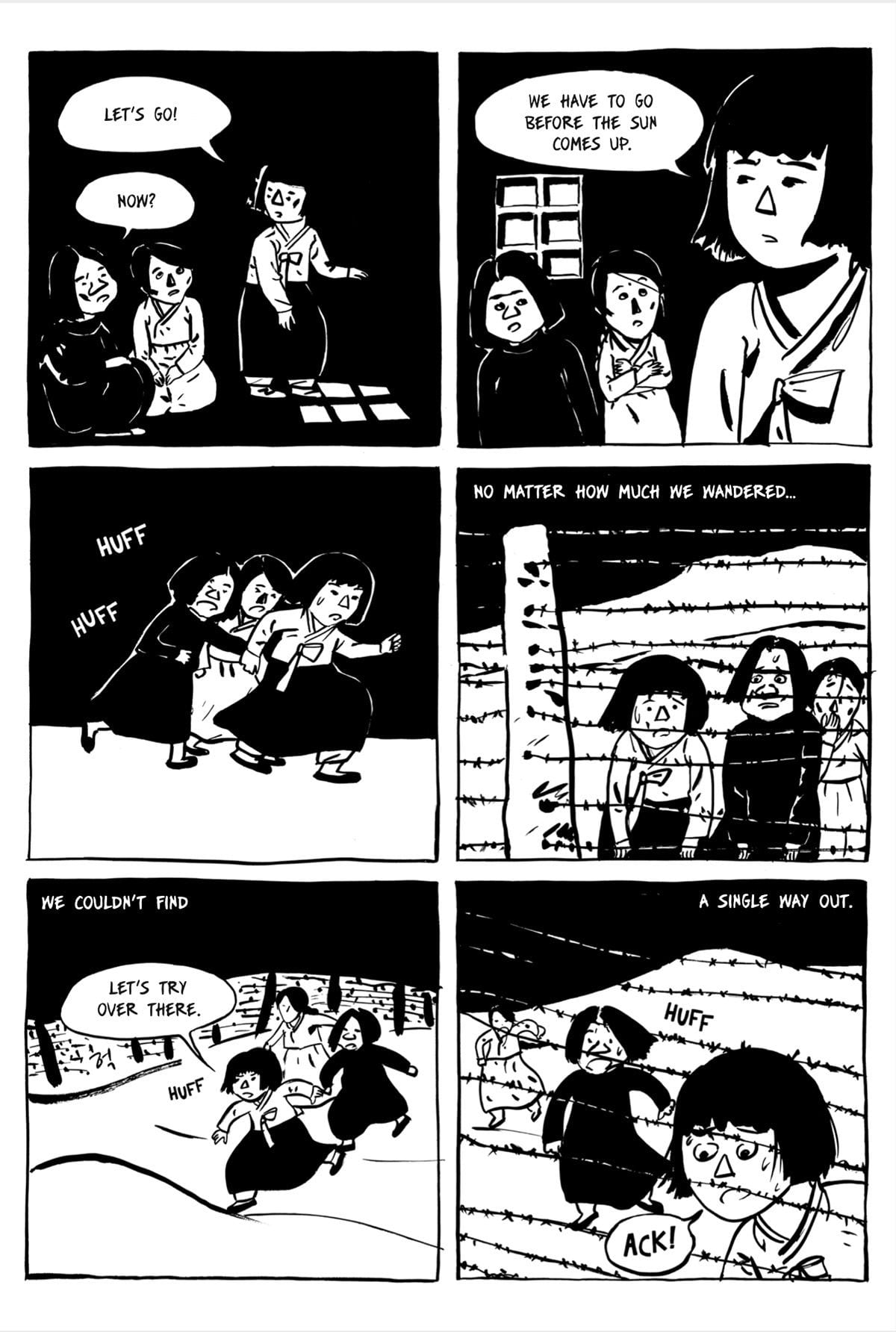

Grass is stark: panels are dark and full of shadows, shading into crepuscular obscurity at especially brutal points of the story. The characters themselves are striking — adults gaunt and angular; children softer and less defined — sketched into black and white panels that make for an appropriate depiction of the grim tale. The author’s black-inked landscape vistas are breathtaking. The narrative alternates between Granny Lee’s childhood and youth, and the sometimes fraught present-day dialogue between Gendry-Kim and Lee as the author tries to gain her confidence and learn her story.

The timing was remarkable. The very summer that

Grass appeared in English, a long-simmering dispute between South Korea and Japan over the latter’s responsibility to compensate victims of WWII-era forced labour – including sexual slavery – erupted into what has been described as a full-blown trade war. As so often, both antagonists in the dispute could learn a lot if they set aside their political agendas to learn from creative interventions like Grass.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

The Japan-South Korean Trade War

For the past seven months, both governments have engaged in what’s been described as a ‘trade war’ but is really just a display of macho chest-beating. Oblivious to the harm they’re doing to their respective economies, labour forces, and regional economic growth, the handful of men driving this dispute in both administrations have even come close to scuttling regional defense agreements.

The present round in this dispute dates back to late 2018, when the Supreme Court of South Korea ruled in favour of the right of former victims of wartime forced labour to seek compensation from Japanese companies.

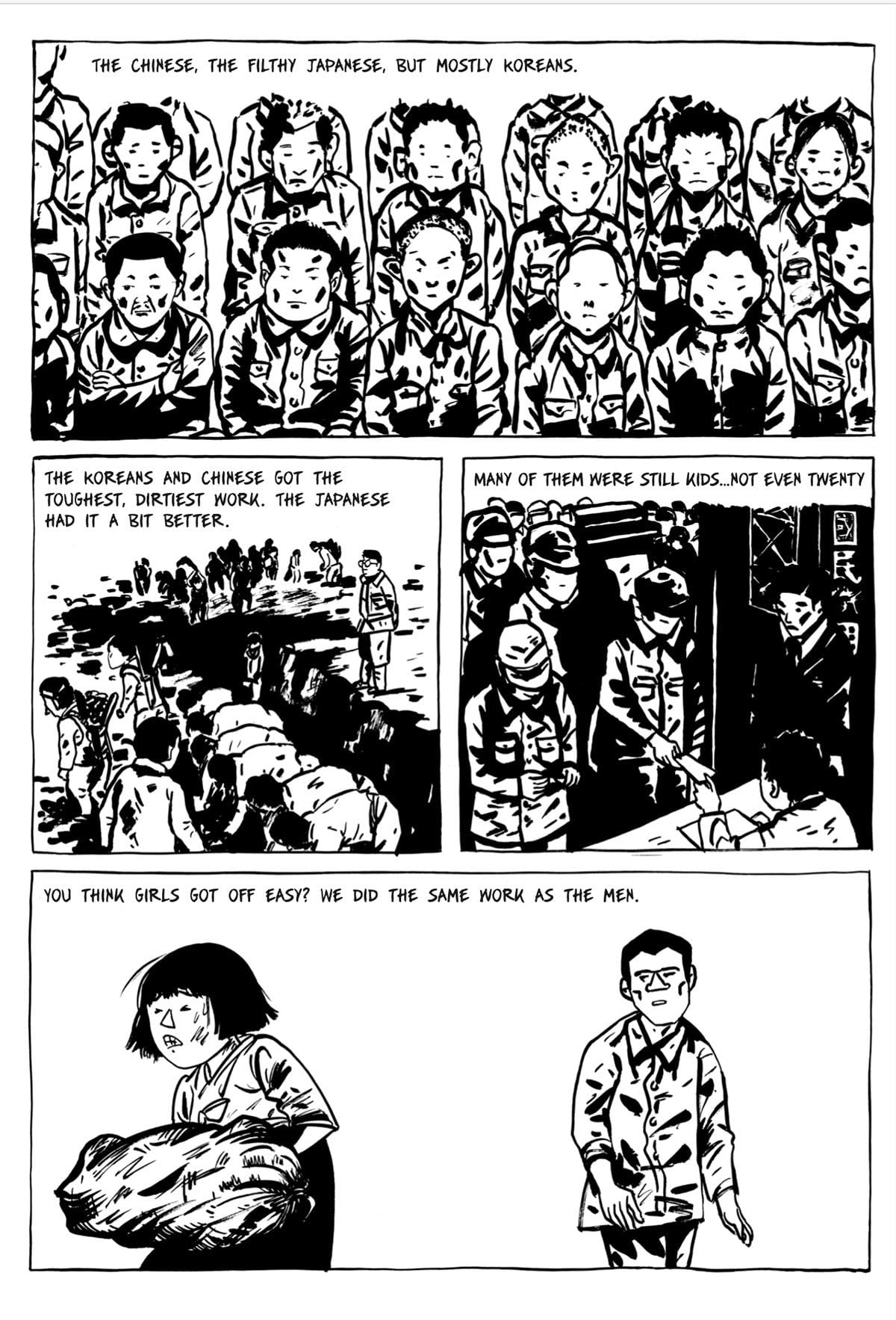

‘Compensation’ is the term being thrown around, but what victims are seeking is some measure of justice. When World War II erupted, Korea had been under military occupation by Japan since 1910, and over five million Koreans were forcibly conscripted into the war effort, including forced labour both in Japan and abroad. This number included over a quarter million Korean women (some estimates suggest close to a half million), most of them under the age of 18, who were forced into sexual slavery by Japan.

Soon after the war ended, negotiations between South Korea and Japan over compensation for conscription and forced labour led to a 1965 agreement in which Japan paid over $500 million (US) in loans and grants to its overseas neighbour. Japan had initially wanted to pay compensation directly to victims, but the South Korean government (then led by President Park Chung-hee, who himself was a Japanese military collaborator during the war) insisted on being the recipient of the funds, which it then funneled into general spending.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Demands for justice for and by comfort women continued. For its part, Japan insisted the issue had been settled by the 1965 agreement (and a couple of half-hearted apology statements made in the 1990s). But in 2015 the two countries (under US pressure and mediation) came to the table and signed an additional agreement on the issue of comfort women, which was intended to see Japan pay roughly $1 billion into a fund for survivors. For its part ,South Korea was supposed to promise to stop complaining about the issue, as well as remove a statue memorializing comfort women from in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul. The agreement, reached by mostly male diplomats from the US, South Korea, and Japan, was largely criticized by comfort women survivors themselves as inadequate.

So in 2017, a new South Korean government denounced the treaty and called for Japan to come to the table and re-open negotiations. Japan, under the conservative, right-leaning government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, refused, and in 2018 the South Korean Supreme Court ruled in favour of compensation suits filed by survivors of wartime forced labour against the Japanese companies that had exploited them. When those companies refused to pay, the South Korean courts in 2019 approved the seizure of Japanese-owned assets in order to fund compensation payments. Japan retaliated with a series of harshly restrictive trade measures, and the two countries launched into a trade war which has continued, with ebbs and flows, to the present.

As political scientist Tom Le writes in the Washington Post, the dispute is the result of “a haphazard reconciliation process and poorly designed agreements.”

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

“I wanted to die”

Media has done a remarkably poor job covering the dispute, which tends to be depicted simply as a trade war with little attention given to the grievances that drive it. The way the issue has been handled – from the ‘power and politics’ style of news coverage by mainstream media, to the negotiations themselves – is essentially the ultimate in transnational geopolitical ‘mansplaining’, with attention focused on chest-beating male politicians instead of the women survivors who deserve justice. Meanwhile, mostly-male nationalists in both countries continue to manipulate and use the issue for their own ends.

Granny Lee Ok-sun’s experience, as depicted in Grass, is a telling one. When she was a young girl in Japanese-occupied Korea, her poverty-stricken family was forced to give her up for adoption to a couple from another town who claimed they owned a noodle shop and would send her to school. They owned a bar and put her to work instead.

When the feisty, spirited young girl resisted, they sold her to a brothel owner who put her to work in the brothel tavern. Then, at the age of 15, she was abducted while running an errand – whether by Japanese soldiers directly, or by traffickers who sold her to the Japanese, she never knew – and sent to a Japanese military-run “comfort station”, or brothel.

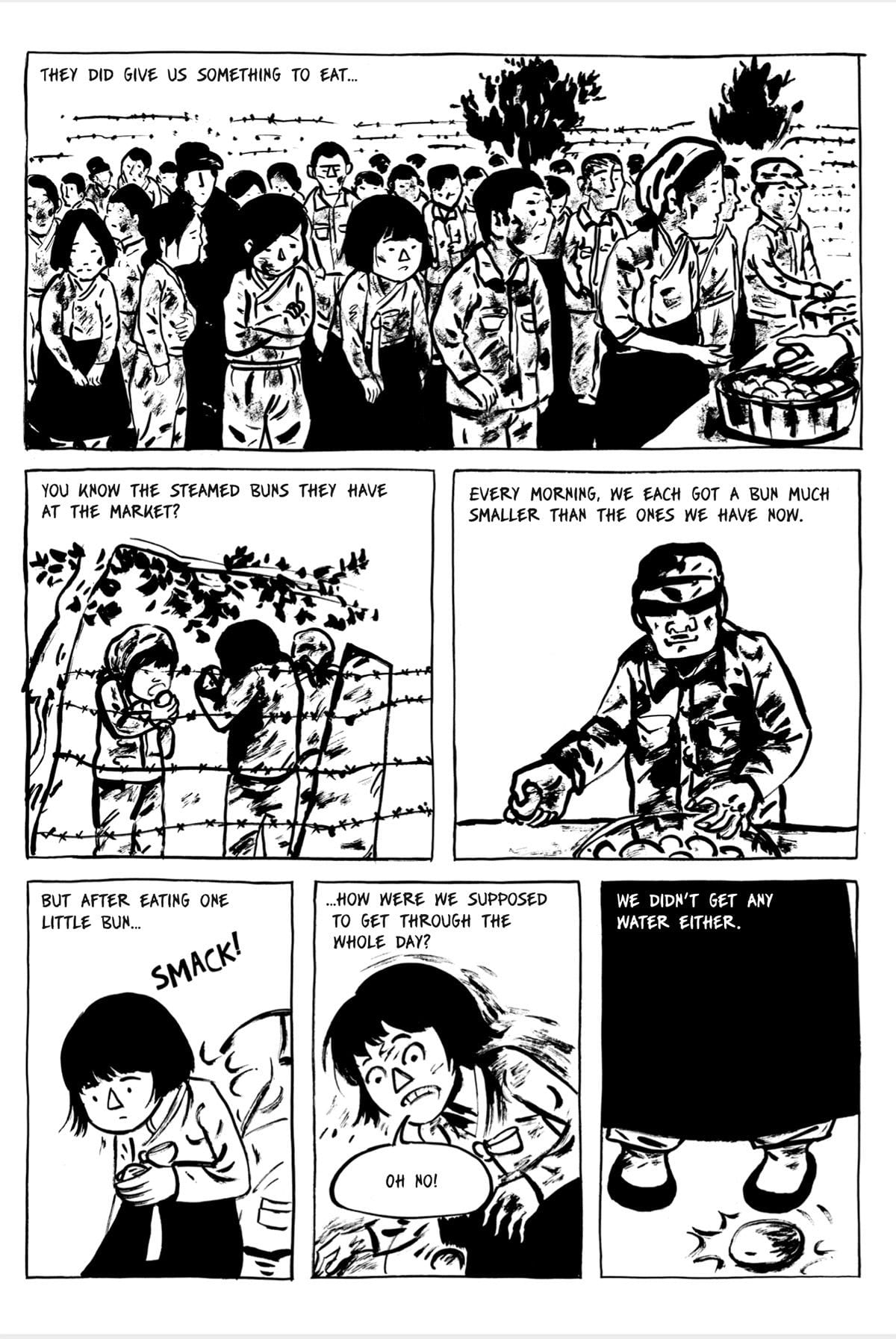

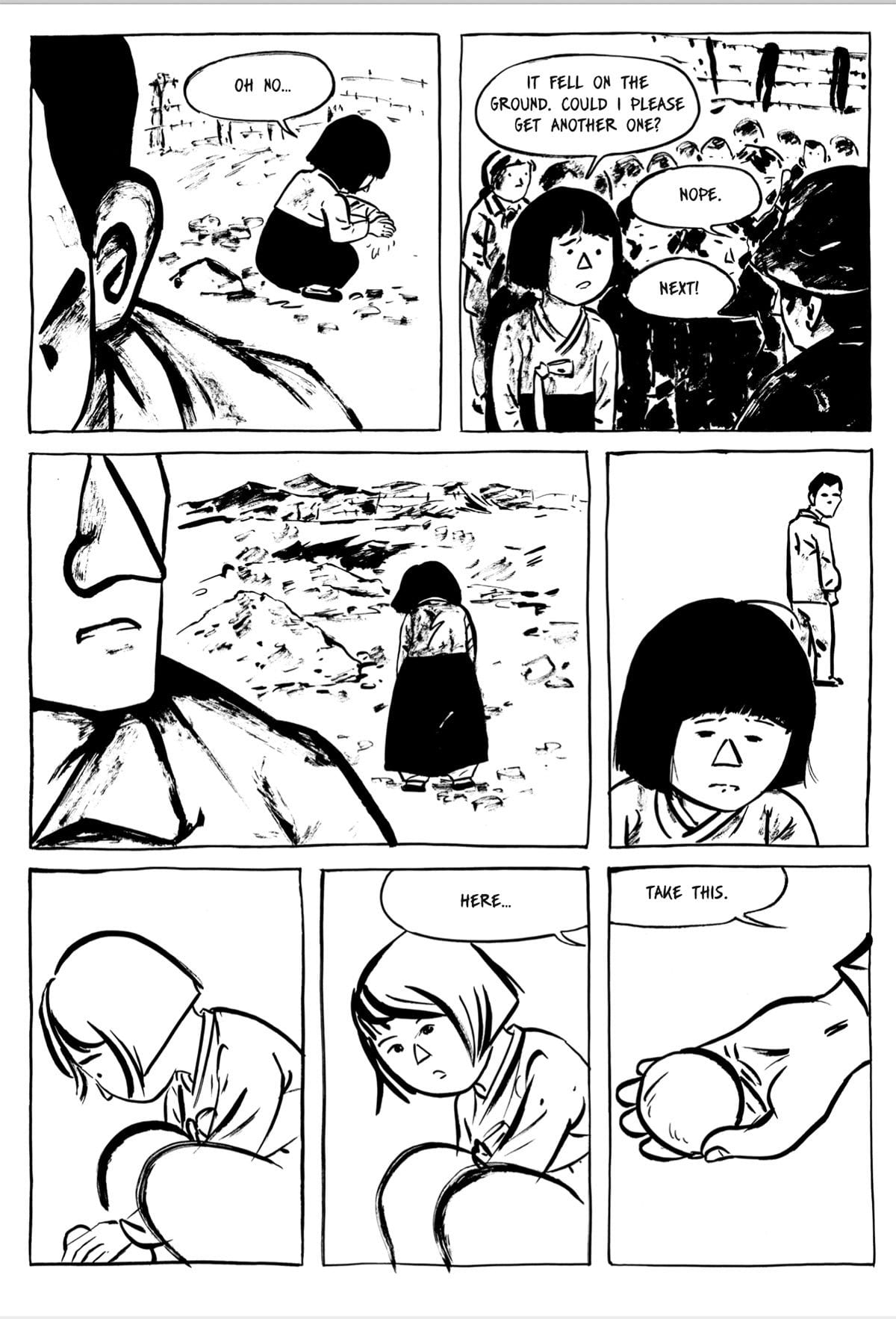

Granny Lee Ok-sun’s descriptions of the experience are simple, straightforward, and brutal.

I bled so much. / I felt so dirty. / That’s why so many girls try to kill themselves after rape. / I wanted to die. / But I couldn’t kill myself. / No matter how much I wanted to, there was no way to do it. / I was alive, but I wasn’t living. / My mother, my father, my brothers, my sisters, my home. / I couldn’t go back to them now. / Not ever.

She got sores on her hands, and her hair began falling out.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

I’d gotten syphilis. I became so swollen down there that I couldn’t receive any soldiers. / Only then did the station managers send me to the hospital. / There I received the No. 606 shot. [No. 606 injections, also known as salvarsan, were used to treat syphilis and other venereal diseases.] / When I didn’t get better for two months / The managers got desperate, since I could make them any money. / They got a hold of some mercury. / They’d gotten it from the medic, who told them to boil the mercury in a small dish and get me to expose my genitals to the vapor. / So the managers forced me to cover my face and squat naked over the boiling mercury. / I got better eventually, but because of that, I could never have children.

She was one of dozens of other Korean women at the camp, most of them abducted as well. One of her fellow prisoners got pregnant. A girl was born, “but when she came back from the bathroom, the baby was gone. The managers had sold her baby off to a childless Japanese couple. / Before she could heal properly, she was forced to receive soldiers again. After receiving the men, so much blood would flow from down there that she couldn’t walk around.”

The suffering of the Korean women did not end with the surrender of the Japanese Army.

“Our suffering wasn’t over yet. The Soviet soldiers came. Those bastards did brutal things. They snatched any girls they saw, raped them, and did whatever they wanted. I saw so many girls raped then shot or set on fire by those monsters,” relates Granny Lee.

Other Koreans suffered through the war only to be killed during Japan’s final throes.

“Many Koreans who had been sent to Hiroshima and Nagasaki against their will became victims of the bombings. They suffered, without even a record of their names, because they were Korean, they were unable to receive treatment. Shim Jintae, the director of the Hapcheon Chapter of the Association of Korean Atomic Bomb Victims, claims that at least 100,000 of the 740,000 victims were Koreans, with 50,000 losing their lives in the blasts,” writes Kim.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Memory and Responsibility

Books like Grass, and accounts like Granny Lee Ok-sun’s, are tremendously important because they help put politics back into proper context. The book reminds us that it is the experience of survivors (as well as the tens of thousands who did not survive) which ought to take centre-stage in disputes such as the present one, not fine points and technicalities pertaining to trade policies.

For the Japanese government to hide behind a series of inadequate treaties rather than take responsibility for the brutal actions depicted in accounts of survivors like Granny Lee Ok-sun, is both shameful and troubling. The issue is not about rule of law or free trade. It’s about a Japanese administration intent on wallpapering over the memory of their genocidal, imperialistic and misogynistic brutalities in World War II.

It’s a struggle with broader implications as well, impelled by a question which drives a number of other contentious, ongoing global struggles: How far does responsibility for evil acts stretch?

Countries as varied as Germany, Serbia, South Africa, Japan and others struggle with a lingering sense of guilt over their role in genocidal conflicts in which the world had to intervene. How deeply does the stain of apartheid stain white residents and politicians in South Africa? What about the legacy of slavery in the United States? The legacy of Indigenous genocide in Australia, the US, and Canada?

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

In the case of Japan and South Korea, the South Koreans who suffered unspeakable horrors at the hands of the Japanese military do not feel Japanese war crimes have been expunged. The Japanese government, for its part, has assertively stated that it considers the matter closed and done with.

Can a nation sign on a dotted line and thereby expunge its guilt for horrifying acts, once and for all? Does payment to some hurt parties automatically free a country of the need to enact reparations for other victims? Is a gesture, even a financial one, enough to close the door on a horrific crime which continues to cause its victims to suffer?

Many would reply: no. Crimes, especially sexual crimes or crimes of power, are ones involving the exploitation of a relationship of power. The guilty party has a responsibility to acknowledge this and be willing to engage in a healing relationship, if it wishes to make right the terrible things that it did. Unfortunately, Japan’s official attitude toward its war crimes – especially those involving brutal sexual violence – suggests the Abe government wishes to treat it like an open and closed case, not one in which it commits to a relationship of healing.

Healing works both ways. If a guilty party does not do what is necessary to help its victim heal, this often means the aggressor doesn’t heal either. Payment of a sum of money in compensation does not mean the aggressor has changed their ways, and that ought to trouble us profoundly. After all, a rapist or murderer would not be released from jail if they simply paid a fine to the victim or family. The judicial system requires assurance the aggressor acknowledges and understands their guilt; that they’ve accepted it and sincerely regret their actions; and that they have substantively and demonstrably changed, before they will even consider allowing the aggressor to rejoin civilized society.

As many scholars have observed, Japan never really endured a substantive process of healing after World War II. Many former imperial officers, corporate allies and war criminals were rehabilitated to positions of power in the post-war government, as the US considered it a more immediate priority to rebuild Japan as a strong regional ally in its Cold War with the Soviet Union.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Healing, Compensation, and Reconciliation

Of course, Japan is not the only state grappling with this type of issue. There are useful and important analogues in the North American experience as well.

In Canada, for instance, a fraught debate over the meaning of reconciliation has marked the struggle to come to terms with the relationship between Indigenous peoples and settler society. Unlike Japan, whose military defeat in WWII brought an abrupt end to its five or so decades of colonial expansion, it’s taken Canada decades to start coming to terms with more than four centuries’ worth of ongoing colonial expansion, both before and after it became a sovereign nation in 1867. This involved not just seizure of Indigenous land through a combination of subterfuge, intimidation, economic pressure and military force; but also systematic efforts to eradicate Indigenous peoples and cultures through measures like the residential schools system, Indian Act legislation redefining who qualified as ‘Indigenous’, the reserve system, and more.

For generations, the Canadian government and corporations pointed to treaties signed with Indigenous groups to defend its land seizures (some of them anyway — much of Canada remains unceded territory). Treaties are still of central legal importance, of course. But the notion that an Indigenous people could cede their traditional territories and rights at the stroke of a pen between two individuals, in exchange for some trade or compensation, has come under rethinking in recent years.

Land agreements and compensation are now guided by the notion of ‘free, prior and informed consent’ – which means that treaties signed under false pretence, in a hasty or manipulative manner, without substantive and meaningful consultation with all those affected, or without full knowledge of the facts may be null and void. As the Australian Human Rights Commission noted in regards to that country’s engagement with Indigenous peoples: “Determination that the elements of free, prior and informed consent have not been respected may lead to the revocation of consent given.”

Clearly, these conditions have not been met in the case of Korean survivors.

The idea that a signed agreement is the be-all-end-all of a relationship between two parties is not so clear-cut anymore. It’s become nuanced by a greater understanding that the basis of such agreements ought not to be the simple stroke of a pen, but rather substantive consent, and that consent is a fluid, ongoing process. Just as sexual consent involves an understanding that it may be redefined and withdrawn at any time, this understanding of consent is gradually being expanded to relationships outside of the sexual realm as well, and particularly those involving relationships of power, culture and identity.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Our understanding of ‘reconciliation,’ too, has become more broad and expansive in recent years.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a government-mandated reconciliation commission that spent seven years (2008 – 2015) documenting the history and impact of Canada’s Residential Schools system on Indigenous students and families, emphasized that reconciliation is an ongoing and collective process: “The Commission defines reconciliation as an ongoing process of establishing and maintaining respectful relationships. A critical part of this process involves repairing damaged trust by making apologies, providing individual and collective reparations, and following through with concrete actions that demonstrate real societal change,” states the Commission Final Report, published in December 2015.

“Reconciliation is not…a single gesture, action or statement” is how Indigenous Corporate Training, an educator organization, bluntly summarizes the point.

The TRC Final Report continues:

Reconciliation is a process of healing relationships that requires public truth sharing, apology, and commemoration that acknowledge and redress past harms. Reconciliation requires constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impacts…Reconciliation requires political will, joint leadership, trust building, accountability, and transparency, as well as a substantial investment of resources.

As Reverend Stan McKay, survivor of a residential school, explained to the TRC (cited in its Report):

The perpetrators are wounded and marked by history in ways that are different from the victims, but both groups require healing…. How can a conversation about reconciliation take place if all involved do not adopt an attitude of humility and respect? … We all have stories to tell and in order to grow in tolerance and understanding we must listen to the stories of others.

An attitude of humility and respect – that’s what has been profoundly lacking from the Abe government in Japan.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Reparations in America

Insight can also be drawn from efforts in the United States to come to terms with that country’s dark legacy of slavery. The movement for reparations for the country’s African-American population (brought to the country as slaves, brutalized and then kept in poverty and precarity through decades of deliberate white American policy-making ever since the Civil War), has intensified in recent years.

But as advocates of reparations also point out, it’s about more than just financial compensation. Reparations for slavery, like reconciliation between Canada’s Indigenous and settler peoples, is a process, and requires all parties to engage in a process of substantive healing and fundamental change.

Zenobia Jefferies Warfield, writing on the topic of reparations in Yes Magazine (Winter 2020), observes that the fraught public debate about reparations for slavery in America “has fomented a more holistic conception of reparations. No longer about a one-time payout to Black folks, reparations today are about collective healing that’s going to take more than a check, a one-time fix – or any single remedy.

Proponents of reparations have adopted a multifaceted understanding of them as defined by the United Nations. It includes restitution, or return of what was stolen; rehabilitation, mental and physical health support; compensation, both monetary and resource-based, which includes a meaningful transfer of wealth; satisfaction, acknowledgement of guilt, apology, and memorial; and guarantees of non-repeat.

Others observe that these goals also require ongoing public education, with attention to how well the spirit of reparations is reflected in legislation and public institutions.

The Abe government’s position that compensation for Korean victims of Japan’s state-sponsored sexual violence was taken care of by the signing of a cheque belies any modern, reasonable understanding of reparations. The money was a start – but only a start. The belligerent attitude of the Japanese government in the face of subsequent compensation claims suggests it has fundamentally failed to understand key aspects of its moral and ethical responsibility in this regard.

In fact, it undermines the integrity of Japan’s previous compensation efforts, by underscoring that the men leading its government really have not demonstrated substantive acknowledgement of guilt or commitment to change. One step forward and two steps back, as they say.

“It’s as if Abe is just waiting for us to die. Does he think he can wipe out the terrible past if all the victims are gone?” reflects Granny Lee bitterly toward the end of Grass.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

“Granny Lee, who had braved the minus 12 degrees Celsius weather to join the weekly Wednesday demonstration [a weekly protest held in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul, demanding justice from Japan for its past treatment of comfort women], denounced the December 28, 2015 agreement between Japan and South Korea over the “comfort women” issue, calling it “wrong” and completely unacceptable,” narrates Gendry-Kim.

“How can an agreement be made without the consent of the victims? How could our government be in cahoots with the Japanese government, instead of speaking on our behalf? / We won’t give up until the Japanese government gives us stronger apologies and compensation. We will keep fighting until the end,” says Lee.

Here Granny Lee joins other activists in accusing the Japanese government of seeking to simply wait out the issue, in the hopes that it will die when the remaining Korean survivors, now at an advanced age, also die. This is not only disingenuous, but it is also unlikely to be the case. White American opponents of reparations in post-Civil War America doubtless also hoped that the issue would die off when the surviving former slaves eventually died off. But it didn’t – more than a century after most of those survivors died, the issue is as fraught and explosive as ever. There is a lesson here for the Abe government, if they will hear it.

Meanwhile, the rest of us may heed our collective responsibility as well, to hear the survivors’ stories and work to prevent such barbarisms from ever happening again. Books like Grass are critically important for the role they can play in educating us all. It’s a harrowing but powerfully written, vitally important book.

“I’ve never known happiness from the moment I came out of my mother’s womb. / Even my sisters and brothers I’d been longing to see, when they found out I’d been a comfort woman, they wanted nothing to do with me,” Granny Lee explains to the author.

Granny Lee’s story is one not only of suffering, but also perseverance. Gendry-Kim ends by reminding us that central to overcoming suffering – and the evils of men — is the tenacious resilience of hope.

The ground that had been slumbering wakes, and the young grass pokes out from between the dead withered leaves. Grass springs up again, though knocked down by the wind, trampled and crushed under foot. Maybe it will brush against your legs and whisper a shy greeting.

(courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

Sources Cited

Indigenous Corporate Training Blog. “What reconciliation is and what it is not“. 16 August 2018.

Tom Le. “Why Japan-South Korea history disputes keep resurfacing”. The Washington Post. 23 July 2019.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Zenobia Jeffries Warfield. “The Collective Healing That Is Owed”. Yes Magazine. 12 November 2019.