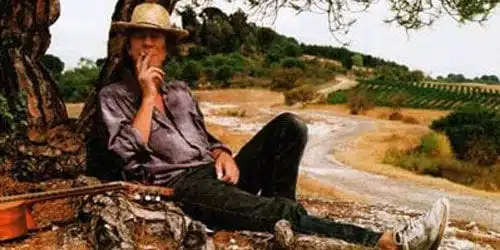

After 15 years of retreat into near-silence, psych pop guru Kevin Ayers has returned with The Unfairground, his homecoming album. It hasn’t been an easy couple of years for Ayers, living quietly and aimlessly in the South of France with no job and no distractions. His emergence from the ether, perfectly poised at a moment when his early solo output seems more relevant than ever, has united a rag-tag group of indie also-rans (members of Ladybug Transistor, Architecture in Helsinki, Teenage Fanclub, Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, and others) to assertively declare before the world that growing old really, really sucks.

The album even opens on this note. The first lines of “Only Heaven Knows” ask “What do you do when it’s all behind you / Everyday something else reminds you / When the times were sweet”? This is an inception by way of an apology. Ayers is sorely sorry that his good days are behind him and thinks that perhaps he might be forgiven for his late ’70s and early ’80s slide in mediocrity if he wears his crusty age on his sleeve this go-around?

Nostalgia of this sort is not a good indicator of what’s to come on the rest of the album. The terrain roved throughout The Unfairground is not unfamiliar, nor is it unwelcome. Indeed, as our rock superstars get older, so too do their fans. The problem is that The Unfairground is often flat, clichéd and just plain uninteresting at times.

Ayers’s vocals on the album sound unaffected and impassive, which is not necessarily odd for him. Many of the man’s best moments paint Ayers as the objective narrator in some musical Mad Hatter story. But on an album dedicated to desperation and longing, which I do believe to be sincere, it’s hard to be moved by such uninspired inexpressiveness.

Ayers’s lackadaisical approach has devolved from a frisbee-light folk prog that fits nicely as a matchbook for either bonfires, joints or candlelight reading into background music for falling asleep in one’s armchair. The good graces of indie microstars and even historically vitalic figures like Ayers’s former Soft Machine bandmate Robert Wyatt (appearing via his handmade Wyattron machine) and friend Phil Manzanera (Roxy Music) can’t even lift the music out of the muddy sand once occupied by Ayers’s nomadic beach bum personage.

Wyatt is Ayers’s perfect foil. Long after Ayers resigned himself to crafting silly commercial love songs, Wyatt was still taking chances and making some of the most challenging music of his career. As a counterpoint to The Unfairground, last year’s Comicopera (one of 2007’s best) finds Wyatt addressing many of Ayers’s same age concerns with a three act song cycle that is heartbreaking, angry, and peppered with new musical directions.

Much of the problem is in the production, which showcases Ayers in the forefront of the mix as a crooner and resigns the sluggish arrangements to mere scenery. The Unfairground‘s many players are equalized into the mix like session musicians on a Michael Bolton LP. Present, but unobtrusive. One gets the impression that many of the numbers here, which for the most part are songs of simple conceits, would have worked better as acoustic arrangements.

“Walk on Water” starts off with some elegant strumming about cooing about people who “Just see what they want to see / Never more than their reflection / In someone else’s fantasy.” In uncomplicated language, the song encourages listeners to be themselves and not to worry about the fortunate ones because they will eventually “reap what they sow”. “Walk on Water” is one of the album’s better tracks, but the strings and brass in the song’s mid-section force a sentiment readily available without heavy-handed orchestration.

Long gone from the instrumentation is the inventive playfulness and manic studio excitement heard on albums like Shooting at the Moon and Whatevershebringswesing, both recorded as the band Kevin Ayers & The Whole World. Ayers abandoned his progressive leanings at around the same time America did, with the backlash of punk and new wave dictating a return to a more rigidly structured pop music hierarchy and a deviance from jazz and experimental influences.

The Unfairground maintains no connection whatsoever to jazz, once a mainstay of Ayers, The Whole World, and The Soft Machine, and even the album’s affiliations with other black art forms are strained at best. “Shine a Light” is the classic white man blues with its unforgivably schmaltzy arrangement and irksome quatrains like “When life was turning / Turning gray / You opened up your paint box / And painted the blues away.”

There’s a vast difference between schmaltz and shtick. Shtick was Ayers’s stock in trade for his first four solo albums. He possessed the uncanny ability to navigate from dark, medieval Canterbury prog jaunts to sundry droplets of island rococo that sound like Blood Sweat and Tears brought up on Os Mutantes. He has accomplished quite a bit throughout his distinguished career, which makes it all the more depressing to hear him sing that he has “nothing left to dream on” or to hear him say “Give me back my dream / I need one to get me through the day.”

Ayers’ experimentalism on his earlier albums often depended more on imagination and ear than proclivity (a lesson learned from free jazz), which is an approach that has a legacy extending throughout the entire independent/DIY music community. It’s absolutely one that the guest musicians from Architecture in Helsinki borrow liberally from. And every single Elephant 6 formation (of which there are a few on this album) wishes they had written “Joy of a Toy Continued”, the madcap trumpet-led psychedelic sing-along from Ayers’s first solo release.

“Only Heaven Knows” also has a parade of mariachi brass marching in Mardi-Gras-like step to Ayers’s conducting baton. Its verse parses a bit from “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood”, angling it via Louis Prima and Jimmy Buffett’s drunken lovechild. Prima, Buffett, and Mr. Rogers are a strange recipe to throw together for a former avant-garde musician looking to regain ground after being out the game for over a decade.

The criticisms often leveled at the Canterbury scene in the era of punk accused it of being too bourgeoisie in that it wasn’t afraid to show its college education. Unfortunately with The Unfairground, Ayers’s accessibility to the middle class is shifting from the college-aged to the adult contemporary.