The young comics fanboy (or girl) whose connection with modern Marvel Superheroes Captain America, Thor, The Hulk and X-Men (among many others) begins and ends in movie theaters will recognize the customary cameos of Stan Lee, who for their purposes is the sole puppet master behind these characters. He’s a pleasant older man with his big glasses, white moustache, and wide grin. At some point during such films he enters the narrative. Maybe he has a line in a New York City crowd scene. Maybe he’s at a ballgame, or Peter Parker’s high school graduation. It’s a wink to the audience and confirmation that this singular old guard who got the ball rolling remains lively, energized into his 90s by the whiz-bam power of colorful comic book panels and continuously growing levels of the Marvel Universe.

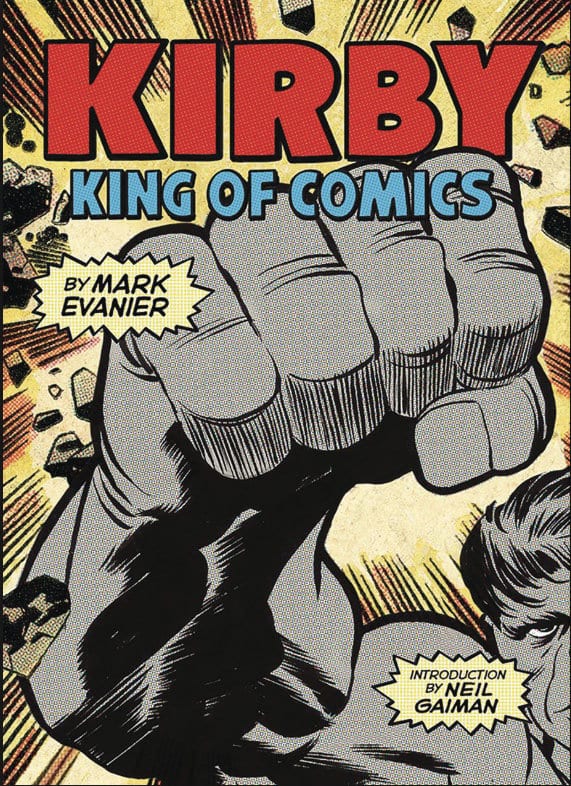

Mark Evanier’s Kirby: King of Comics, originally released in 2008 and now in a 2017 affordable anniversary edition with a new chapter that brings its subject’s story up-to-date, aims to set the record straight regarding the life, times, and legacy of Jack Kirby. Not only was he responsible (with partner Stan Lee) for co-creating the aforementioned heroes, but after his acrimonious departure from Marvel in 1970, Kirby went on to rival DC and created the “Fourth World” series, featuring “New Gods”. He returned to Marvel in the mid-’70s to work on such projects as Black Panther, Captain America, and an adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The connections to the old days might not have survived, but the colorful majesty of the characters remain as strong as ever.

It’s hard to say that Jack Kirby is an unsung hero, but he certainly did not get his full due during his lifetime. Dead in 1994 at the age of 76, Kirby started his life and drawing career in New York City’s Lower East Side. “All his life, Jack Kirby wrote and drew what others wanted.” In 1983’s Street Code, Kirby came as close as he probably ever had to an autobiography. It was commissioned by Richard Kyle, a Long Beach California underground comics store owner. As Evanier puts it, “Kyle decided to commission a story… printing from the pencil art without an inker coming between Jack and the audience.” The images conveyed in muted greys, whites, and blacks are remarkably powerful. A boy in a crowded tenement apartment tells his harried Mom he’s going out. She’s worried he’s going to hang out with bums, but he assures her it’s just to play ball. “Mothers and old ladies were somehow sacred to all the guys,” we read in a thought bubble as the boy makes his way down the stairs. “I never questioned the rule.” The story becomes more vivid and violent as the boy engages in a rumble with the gang. In the final panel, there’s a close-up of the boy and more voice-over declarations in a thought bubble:

“But, I was hurting—hurting for Georgie and me—and the lousy things we had to do for the street code.”

As is common with most narratives about comic artists of the era, this is a story of laborers churning out product without concern about deep themes or aesthetic quality. It was all about volume and variety:

“Jack loved the diversity of the job as he vaulted from world to world, spending his mornings drawing pirates and his afternoons in space.”

The life of a great cartoonist was also about finding mentors and serving apprenticeships, and for Kirby that came from Will Eisner, who he called “My friend, teacher, and boss, not in that order.” Captain America surfaces in the late ’30’s/early ’40s. With his partner Joe Simon, Kirby created Captain America as that one character willing and able and eager to punch Adolph Hitler in the face. Typically, this brave audaciousness resulted in death threats from American Nazis, even if the legendary New York City mayor assured Kirby and company that “…’You boys are doing a great job and the city of New York will make certain that no harm comes to you.'”

Stan Lee would enter Kirby’s world in the ’40s as an assistant to Simon and Kirby. They were with DC, and WWII entered the fray. Evanier writes of Kirby’s experiences in the war: “Even half a century later, he would still revisit the Big One in his dreams, often waking up alongside Roz [his wife] in an icy sweat.” It’s a little frustrating in a story as big as Kirby’s that the war experiences are not fully detailed. Evanier does do it well, and the reader gets the sense that Kirby was like many of his generation in that he chose to keep silent and let his work do the talking, but some of the images (like copies of letters Kirby sent home to his wife) are truly striking. Kirby: King of Comics could have benefitted from a more concentrated focus, even in a life and career as legendary as Kirby’s.

Before the superhero franchises of the ’60s, which Kirby and Lee and company latched onto and never let go, the idea was to find the wave and ride it to the end. There were war comics, detective stories, crime drama, and romances. Covers from titles like True Love, Young Romance, and Young Love are reproduced here and they seem interchangeable. The Archie series was more gentle and perhaps realistic. The teens looked like teens. In Kirby’s work, romances seemed to mirror the film noir of the ’40s and the Douglas Sirk melodramas of the ’50s. Add Black Magic (horror) and Captain 3-D (latching on to a fad) and the cycles continued. Titles like Foxhole were “…written and/or drawn by men who’d been there, done that.” According to his wife, Kirby “‘…would have been very happy to spend the rest of his life just drawing the war stories he told everyone all the time.'”

This is probably one of the more frustrating elements of Kirby: King of Comics. Where is the best focus for this story? Should it have been about the superheroes of the ’60s and how they remain vital today? Should it have been about the dynamics between Kirby and Lee? The biggest details come in the second half of the book, and they’re a little ponderous. It’s a lot of “inside baseball” about bad financial deals and ownership of characters. Who created what? How? Who should be the human face behind the superheroes? Kirby: King of Comics works best when reproducing stories from 1954’s Fighting American as they exposed “The League of the Handsome Devils”. Some of the dialogue is priceless. Having literally unmasked one of the grotesque villains, Fighting American gives him the bottom line:

“Ugly men have found a good place without resorting to mugging and killing! No, your motive was something else, besides bitterness!”

Halfway through Kirby: King of Comics, we get some interesting background about the origin of The Fantastic Four. While Evanier notes that Kirby related to The Thing, that human seemingly made of orange rocks, he looked more like Mister Fantastic. The first issue of The Fantastic Four, on 8 August 1961, marked the ascent of Marvel from a tiny company to a world player. Evanier sees it as comparable to the June 1938 first issue of Action Comics and the debut of Superman. Nothing would be the same after both titles came to define the world of superheroes. What distinguished Marvel from the others was superheroes with real-life issues, like Bruce Banner becoming the Hulk and Peter Parker becoming Spiderman. Kids became emotionally invested in these stories as the real world around them was falling apart.

The casual fan may get lost in the stories of bad financial deals and the marketing machinery of the comics industry, and any fan would probably like a deeper dive into characters like The Silver Surfer, which was apparently a major point of contention between Kirby and Lee by 1967. Lee was the better interview, the better editor, the better face of the company, and Kirby was more comfortable drawing the characters. Some of the ’70s work from Kirby, like the drawing collages of Metron and Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen, seen in Kirby: King of Comics, are truly fascinating and deserve a deeper dive.

By the end of Kirby: King of Comics, most readers will appreciate this story of a life well lived. It’s a major accomplishment and a loving survey of the different phases of a comic creator’s career. It’s just frustrating that like a comic serial itself, the biography couldn’t have been isolated in different phases. There’s almost too much here. Its major assets are the beautiful color pages and generous samples of strips in progress through the course of his career. Writer Neil Gaiman offers a touching opening tribute in which he argues that a perfect world would feature a Kirby Museum and Evanier as your guide at every stop of the way. While the craft Kirby so lovingly embraced required an allegiance to solitude, the strongest stories are about partnership. Here’s an account of Kirby’s funeral in 1994:

“Half the industry turned out for the funeral, and the other was present in spirit. Stan Lee was there in both capacities, sitting quietly… departing without saying much of anything to anyone. Roz wanted to give him a big hug… to show that what was done was done… But Stan, quick as ever, was in the parking lot… gone before she could get near him.”

It’s a scene that embraces the pathos and loneliness beneath so many of the heroic story lines and images in the comics of Jack Kirby. No matter if they were immaculately conceived or the product of a partnership, they always slipped away like a thief once the final page was turned. Kirby: King of Comics leaves some of its subject’s life storylines in original charcoal sketch form while embellishing some that don’t need clarification, but as a final product it’s a beautiful book. If anything, it proves that the Marvel Universe lives and dies on paper. The films are fun, but they barely scratch the surface.