If a ranking of the most unpredictable acts in musical history is ever compiled, Laibach are sure to be strong front-runners.

The Slovenian avant-garde musical/artistic collective has been challenging boundaries – and that’s really the only precise way to put it – since the early 1980s. Behind the Iron Curtain, they courageously challenged totalitarianism in the immediate post-Tito-era Yugoslavia with experimental industrial performances, parodying the police state by performing in uniform and projecting creative – often lewd – mashups of government imagery. They toured Europe, frequently mistaken for a neo-fascist band due to their incredibly effective parody and pastiche of totalitarian imagery, which combined military uniforms with neo-classical and martial-sounding music. Indeed, they deliberately drew on fascist imagery and popular culture with the aim of subversion, yet their subversiveness was so subtle and clever it was (and is) frequently mistaken for the real thing.

In the years which followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and then Yugoslavia, they leveled their parodic aim at both east and west in equal measure and developed a knack for parodies and spoofs of pop culture hits, from the Beatles to Queen. In rendering their covers, they sometimes reinterpret originals in industrial, techno or bombastic neo-classical form; other times they maintain the song’s original sound but slightly re-work the original lyrics so as to slip in incredibly potent and pun-nish political statements. Subtle word changes, awkward pauses and shifting the emphasis on different parts of a song’s lyrics are among the tools they use to force a reevaluation of what some of rock music’s canonical anthems are really trying to say.

If there was ever a band that took their post-modern politics seriously, it was Laibach. Yet for all the ambiguity and provocation of their performative politics, they make downright great music too. Their more upbeat, techno tunes are imminently danceable, while their neoclassical scores are majestic and beautiful.

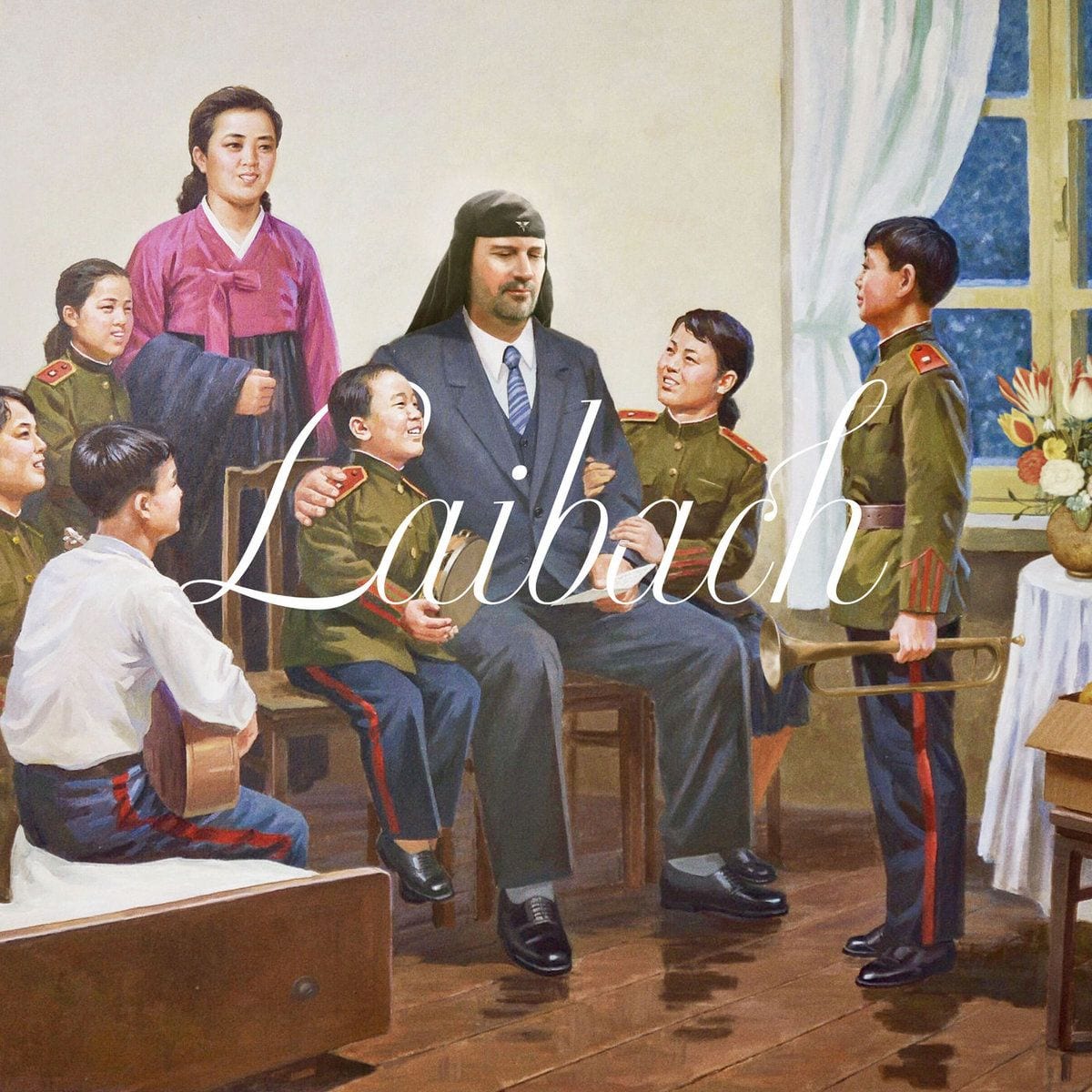

Yet by far, their most tremendous and bizarre coup has been their 2015 concert in Pyongyang, capital of North Korea. They proudly became the first western rock band (though some might dispute the ‘rock band’ label) to perform in the notoriously isolationist totalitarian country. Their performance was met with outrage in some quarters, bewilderment in others. Laibach calmly took it in stride.

“There is no second chance to play in Pyongyang for the first time,” band member Ivo Saliger told Rolling Stone, with characteristically straight-faced Laibach levity. “Laibach has, since its very foundation, been dealing with totalitarianism in all its manifestations; therefore visiting North Korea was absolutely a must-do.'”

Fair enough. Leave it to an anti-fascist rock band and radical art collective to suavely steal the headlines from the politicians who were grappling with the phenomenon which is North Korea. Laibach’s visit – a documentary film, Liberation Day, was produced about the event by Norwegian filmmaker Morten Traavik – was as surreal an event as could be imagined. At their welcome dinner, a government official courteously denounced them as “evil pornographers”. They battled with North Korean government censorship committees over concert visuals and had to drop their renditions of a couple of North Korean folk classics yet were allowed to retain images of American rockets. Footage of their concert shows audiences that appeared bewildered yet polite (even while plugging their ears). The Syrian ambassador, who attended, called the experience “torture”, while an elderly North Korean attendee was more reservedly polite: “I didn’t know that such music existed in the world and now I know.”

As for Laibach, they seem to have enjoyed the experience, which is not likely to be soon forgotten by the North Koreans they encountered. They gifted a theremin to the Kum Song school of music and reported that the local beer and cannabis were great.

What sort of songs did Laibach perform at this bizarre, unlikely event? In addition to some of their classics (like their cover of the Beatles’ “Across the Universe”), they fashioned the bulk of their performance around – yup, you guessed it — covers of songs from The Sound of Music.

For those who were unable to make the North Korean shows (understandable, perhaps) Laibach has now released these renditions on the forthcoming album The Sound of Music. Featuring tracks produced both at the event in Pyongyang as well as after the fact in Laibach’s native Slovenia, the album falls on the more subtle side of Laibach’s musical spectrum. Musically the tracks loosely approximate the originals, with the exception of the heavy, rasping East European-accented masculine vocals which feature on many of them.

The title track is a piano-driven rendition, incongruously coupled with those guttural, accented vocals. A similar approach is followed with “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” and “Do-Re-Mi”. “Edelweiss” takes things in a more unusual direction, opening with what sounds like a harp, then adding some electro-disco beats, and mixing in angry, off-tune vocals.

“My Favorite Things” opens with light and ethereal vocals, mixing in ghostly piano sounds. Then the primary vocals kick in sounding upbeat and almost sweet for once; the vocalist shares a lyrical stage with a chorus of children. The overall effect of this track is actually quite charming, rendering the track into something nearer a heartsick ballad or aspirational hymn than its more playful filmic version.

“The Lonely Goatherd” — the track performed during that remarkable puppet play in the original film — also conveys the feel of a love ballad, replete with light piano keys and breathy vocals (one can’t help wondering whether this is actually what the track might have sounded like had the Von Trapp children had access to computers and synthesizers when they put off the puppet show).

“Sixteen Going on Seventeen” is a duet, but rendered in imminently creepier form than the original. “So Long, Farewell” also opens with lovely piano music and children’s choral vocals, but quickly breaks in with an electronic beat and growling male vocals.

Laibach include a few tracks they were not permitted to perform in North Korea, including the brilliantly punned track “How Do We Solve a Problem Like Korea (Maria)?” They also include excerpts from their welcome speech, and their rendition of the Korean folk tune “Arirang”, which holds anthem status in North Korea.

All in all, it’s an intriguing album, enjoyable largely for its novelty factor as well as an appreciation of the remarkably audacious artistic and political statement Laibach made by performing the concert in North Korea in the first place. Truly an artifact of an artistically authentic, cold war-era radical sensibility which predates today’s insipid art movements, the album is one of those which will make you think more than it’ll make you dance. In this day and age, that’s certainly something we could all use more of.