While numerous scripters, pencilers, inkers, and the occasional colorist vie for authorial recognition in the comics industry, the lowly letterer remains the least lauded of contributors. Marvel’s star scripter Brian Michael Bendis tells aspiring writers: “Lettering should be invisible. You shouldn’t notice it.” It’s no surprise then that a letterer’s name never appears on a comics cover.

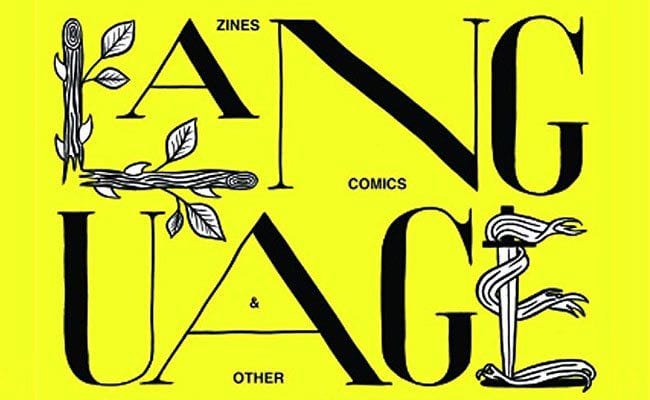

Or almost never. In addition to comics artist, illustrator, and graphic designer, Hannah K. Lee is a professional letterer and the lone author of Language Barrier, a pleasantly perplexing amalgam of one-page comic strips, single-issue zines, and stray experiments in the comics form. By pushing at the ambiguous border between words and images, Lee gives new meaning to comics pioneer Will Eisner’s observation: “WORDS ARE IMAGES!”

Even Bendis acknowledges that lettering needn’t be invisible if “it is a determined piece of storytelling in graphic design” — a description of nearly every page of Lee’s collection. In the most extreme cases, like the two-page spread “Millennial” that concludes the book, letters are the only graphic element. But more often Lee combines words and pictures. The yellow letters of “You don’t owe anyone anything” contain warped smiley faces, much of “Nowhere to hide” is obscured by blades of grass, and clusters of eyes dot and cling to “Beautiful! We see you”. Sometimes Lee’s letters seem to fight to emerge from webs of similar shapes, adding irony to “Everyone knows your name” and “You are popular”.

Even when Lee renders words in familiar fonts, she finds other visually playful ways to disrupt their meanings. For the sequence “Close Encounters”, she isolates each word, floating their letters in white space for the reader to piece together while also puzzling through their relationships to juxtaposed images. The fractured letters of “Change” hover beside a ribbon knotted around an impossibly thin neck. The letters of “Nervousness” dot the spaces beside and between a wavy tuning fork. Even when letters cohere easily, their accompanying images challenge simple interpretations — as with a sheet dangling from a clothesline beside the phrase “A soul leaving a body.” The graphic quality of the words are stable, but their semantic qualities continue to shift unpredictably.

Lee also explores images in isolation. The typically white background of the opening, title, credit, and closing pages feature wallpaper-like renderings of commercial product characters: the Chicken of the Sea mermaid, Chiquita banana’s Carmen Miranda, the smiling figure of Sun-Maid raisins. Though unaccompanied by product logos, the iconic images evoke the words Lee eliminates. Roughly a third of the collection consists of other wordless images, some free-standing, others in sequence. The 17-page “Shoes Over Bills” lovingly details a collection of women’s shoes, with juxtaposed phrases “Credit card debt” and “Emergency dental work”. “Hey Beautiful” is an appropriately fragmented sequence of a female body shattered and collected in a still-life fruit bowl. It also includes free-floating words, presumably spoken by a male voice offering compliments, insults, and offers to mansplain Radiohead and Battlestar Galactica (the original).

Such gender analysis is central to Lee’s larger project. “Interpreting Emoji Sexts” offers contrasting translations of Lee’s hand-drawn rendering of ambiguously suggestive emoji combinations. Another two-page spread offers valentine candies with the unlikely phrases “Equal chore distribution” and “I like your body hair”. “Penises” consists of one-page comics arranged in traditional grids and features a cartoonishly rendered woman assessing the undrawn, but graphically implied shapes of her changing lovers.

Lee opens the collection with a similarly traditional comic, the four-page “1 is the Loneliest Number”, that explores the unlikely benefits of living alone. It’s a welcoming entrance into what soon evolves into a comparatively anarchic exploration of the outer edges of the comic form. If you’re looking for conventional storytelling with a main character narrating the travails of contemporary dating, this at first glance, this may not be the book you’re looking for. But overlooking Language Barrier would be a shame, because Lee explores that same subject matter to better effect by abandoning panel grids and just-like-life characters and diving directly into the deep end of the image-text pool. Formal experimentation is rarely this much fun.