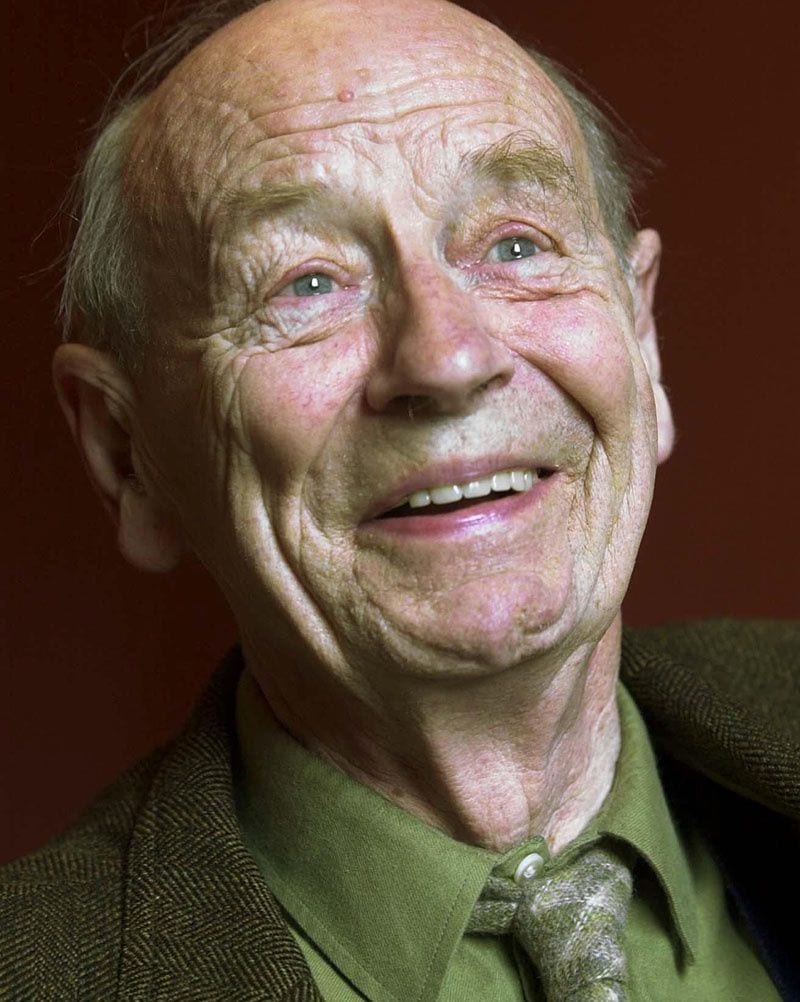

William Trevor was that rare one: popular with readers and a writer’s writer. When he passed away in late 2016, lengthy tributes from well-known literati flooded in and they seem to never have stopped. With the release of this posthumous collection of his last short stories, there has been, and rightly so, another surge in appreciation.

With 13 short story collections, two novellas, and 14 novels, he was one of the few writers who did well with both the short and long forms. Having come to full-time writing later in life — after a career as a professional sculptor and an advertising copywriter — his obsessive, disciplined writing practice ensured more than half a century’s worth of stories as his enduring legacy.

He is most appreciated for, among many things, his empathetic and realistic portrayals of women. At a time when the literary world is scrutinizing how male writers write about women (read Talia Lavin’s essay in Village Voice), Trevor’s reputation has remained unsullied. His consistent explanation to the frequent question of how he did that was to say that he was simply curious about and wanted to understand women better (listen to the BBC Radio 4 Book Club podcast.)

Whatever questions Trevor sought to understand better — with all his characters, not just women — he often returned to explore them in different ways. In this, he was much like the 19th-century playwright, Ibsen (see Georg Brandes’ critical study of Henrik Ibsen.) That said, Trevor was not looking for answers necessarily. Mostly, he was aiming to frame the questions better each time in order to, as Chekhov famously wrote (see his October 27, 1888 letter to A S Suvorin), correctly state the issues rather than solve them.

Like Ibsen, Trevor left his own country to gain distance so he could write about it better. An Irish Protestant, Trevor made England his home for several decades. When pushed to claim a nationality, he always said he was an Irish expat. Still, he approached all his writing with that angled perspective of the perennial outsider, saying in a telephone interview with The New York Times:

As a writer one doesn’t belong anywhere. Fiction writers, I think, are even more outside the pale, necessarily on the edge of society. Because society and people are our meat, one really doesn’t belong in the midst of society. The great challenge in writing is always to find the universal in the local, the parochial. And to do that, one needs distance.

This sense of placelessness and isolation underpins all his short stories too. Yet, for a writer who wrote marginalized characters with so much understanding, it’s surprising that his stories have rarely included people of other races or ethnicities, even as minor characters — especially those set in London. But we do not go to a Trevor story to look for ourselves. We go to a Trevor story to understand other people. As we must with this last set.

There are ten stories in this collection. The recurring themes of loneliness, death, betrayal, delusion, and loss might make them sound rather bleak but his spare prose and concise narratives avoid melodrama or repetition. All the main characters struggle with and never conquer their yearnings, which are challenged or thwarted through singular moments of quiet drama. And, despite there being no radical or titillating action, what lingers in the reader’s mind long after reading feels like reverberations of aftershocks.

One particularity that animates several of these stories is how two unlikely characters come together: a middle-aged caretaker and strange European workmen; an amnesiac picture-restorer and a street prostitute; a widow and a widower from different social strata.

The lonely, older woman of the shabby, genteel kind is a recognizable Trevor archetype here. As ever, though, Trevor’s unfailing compassion and understated humor serve as reliable anchors to prevent the pathos-filled narratives from sinking into sentimentality.

The first and last stories are the strongest. With ‘The Piano Tutor’s Daughter’, a single, middle-aged piano tutor finds her best pupil is stealing from her. The way Trevor unfolds how the awareness comes upon her and how she responds to it is so masterful because, in that short narrative space, we also get a sense of the woman’s entire life and her major disappointments — all of which make the ending so bittersweet. With ‘The Women’ (read in The New Yorker), the two older women are retired friends living together but lonely in their own ways. The story is really about a young schoolgirl they are trying to become friends with and Trevor captures her confusion and desolation, especially at the end, in a pitch-perfect manner.

With endings, an abiding hallmark of a Trevor story is how he opens up various possibilities for a character’s arc early on and yet, when the ending arrives, it is satisfyingly inevitable. That said, some of the endings in this collection are left vague, almost framed as potential new beginnings for the next momentous life event that readers can contemplate what-ifs about. In ‘Taking Mr Ravenswood’ (read in The Lit Hub), we are left conjecturing about what transpired between the bank clerk and her rich customer back at his house after a dinner date. In ‘The Unknown Girl’, we never get an understanding of what drove the cleaning woman to her death in the beginning even with the sort-of-revelation from the protagonist’s son at the end. In ‘Mrs Crasthorpe’ (read in The New Yorker), flashes of the newly-widowed woman untold past interlace with difficult moments of her present and, while this helps us see her pain and neediness, we never know exactly what sends her to her unfortunate end. In ‘Making Conversation’, we never find out whether the protagonist’s stalker has disappeared for good or whether he will return to his wife; ‘Caffe Daria’ has another disappearing act at its close — this time, the protagonist’s ex-friend, who had stolen her lover.

Such ambiguity is deliberate. Trevor has avoided pat explanations of how people are and given readers the space to see and understand for ourselves. To allow readers to engage in this manner with a short story that is compressed to its minimum is very difficult. Beyond writerly skill and confidence, it also demonstrates a graceful respect for the reader’s intellectual abilities.

Speaking of reader engagement, a Trevor story is best read (or reread) closely for the precise details and clues that lead to the only closure (or lack thereof) feasible. One such example in this collection is ‘An Idyll in Winter’ (read in The Guardian). It’s about a cartographer who meets the woman he tutored when she was a child and he was a young man. Leaving his happy (until then, anyway) family, he moves in with the former pupil. Reading close enough, from the very start and at almost every step, we can see there will be a romance. But we cannot predict, till near the end, its final shape. Incidentally, this story is also the only hope-filled one in this collection. Consider these last lines about how love goes on even when a relationship does not:

Mary Bella senses an anxiety, and pity perhaps. She doesn’t try to smile any of that away, only wishes the men could know that love, unchanged, is as it was, is there for him among her shadows, for her in rooms and places as familiar to him as they are to her. She wishes they could know it will not wither, that there’ll be no long slow dying, or love made ordinary.

If we have paid attention, we can see how that echoes these two simple lines from earlier:

It made her sad that the summer had to end. He said it never would, because remembering wouldn’t let it.

There are many such earned rewards from a slow, close reading of a Trevor story. This is why he is a writer’s writer. Each of his stories can reveal clever tricks of the trade. Each can be a mini masterclass in the art of the form because he compels us to slow down, stop, and observe carefully the quotidian, everyday moments that we mostly rush past in real life. We emerge from a Trevor story rubbing our eyes and seeing the world around us more clearly. Aughor Yiyun Li describes it as “mental Visine“. Mostly, he enables this through an economy of language but also by rationing out just the necessary details at the appropriate times.

That language, though, will sometimes sound anachronistic, especially to younger readers today. Descriptors like “mobile telephone” and characters writing with fountain pens rather than using text/email might feel strange to some. This is small price to pay, surely, for the experience of inhabiting the varied worlds of Trevor’s stories — worlds that are filled with “explosions of truth” and “total exclusion of meaninglessness”, as he said in his definition of the short story in this Paris Review interview.

Julian Barnes’ insightful The Guardian essay ends with the second-best description of a Trevor short story (and, perhaps, the best one of the writer himself):

Automatically, we predict where the story might be going. But it doesn’t go where we predict, because, in a way we sense rather than observe, it has ceased to be a story. It has become life, and life wrongfoots us in stranger ways than fiction can. We submit to the deep, essential truth to life that Trevor has presented. And yet, at the same time, we realize it is still “only” a story.

None but those with a complete mastery of fiction can walk this line. William Trevor was not “an Irish Chekhov” or even “the Irish Chekhov”. He was and will remain the Irish William Trevor.

- William Trevor - Literature

- William Trevor, my father: 'Writing was what kept him going'

- William Trevor | The New Yorker

- Paris Review - William Trevor, The Art of Fiction No. 108

- Mohsin Hamid | Terminator: Attack of the Drone | Books | The Guardian

- Full text of "Henrik Ibsen: Critical Studies."

- BBC Radio 4 - Bookclub, William Trevor

- Twenty Years Ago, “Sex and the City” Redefined the Single Girl in ...

- Last Stories by William Trevor | PenguinRandomHouse.com

- William Trevor interview | Good Afternoon | Mavis Nicholson ...

- William Trevor, Hidden Ground. 1990 BBC NI documentary. - YouTube