Life, in Pictures, the collection of Will Eisner’s autobiographical comics and graphics novels, cleanly articulates the value of owning a book more for history’s sake than for enjoyment. This is not to say that this Eisner anthology, the third which has been released, is vacant of those endearing qualities (pacing, humor, dynamic illustration, engaging storytelling) that makes the reader happy about his decision to pick up a graphic novel.

Indeed, the collection boasts all of these virtues, Eisner having set the bar for many criteria by which comics are judged. However, one does not necessarily take away an immediate impression of any of these graces as their merits are deluged by the overwhelming mood of the compilation: abject misery.

Although none of the stories are one-to-one replications of Eisner’s life or those of his parents, the grandfather of comic-dom strives to approximate the milieu of the hardships surrounding his and his family’s existence. This includes: the struggles of his Jewish father in anti-Semitic Europe and, later, anti-Semitic New York (To the Heart of the Storm), the turbulent life of his mother and her family in outrageously classist New York (The Name of the Game), Will’s own difficulties growing up in anti-Semtic, outrageously classist New York (The Name of the Game), the adversity Will faced trying to succeed as a Jewish comic in depression-era New York which is still — you guessed it — anti-Semitic and classist (The Dreamer), and finally Will’s difficulties with retirement and old-age (A Sunset in Sunshine City). Throw in a fair share of just general awful human nature, ubiquitous adultery, and a nice queue of deaths and the formula for Life, in Pictures is complete.

If this synopsis sounds repetitive, it is only to emulate the feeling one gets when reading through this anthology. By its conclusion, the reader will be so mired in the oppression of both Jews and the lower-class that their soul will likely be crushed. Just when you think a character’s luck can get no worse or their soul more corrupt, that character indeed plummets deeper into misfortune or vice (often both). At times it actually becomes admirable that Eisner has found a way to string together peripeties that are all turns for the worse — try to illustrate that in any sensical geometric representation.

Furthermore, had these tales adopted a Horatio Alger format and ended in redemptive success, perhaps the blow of Eisner’s incessant desolation would be undercut. While this almost occurs in The Dreamer, the rest of the stories end in some limbo between icy-inertia and full-on sadness. Eisner actually changes the events of his life “play what-if” and make his comic representation an adulterer to his wife who was born, in the story, essentially out of rape and raised by a narcissistic, morally bankrupt father and drunken, lush mother.

However, as mentioned earlier, Eisner is absolutely adept at his craft and all of the stories are benchmarks of every aspect of the medium. His dialogue is natural, his plots are engaging, and his characteristic style of drawing is fantastic. Characters’ faces contort wildly (but never absurdly à la animé) with their emotions, making them often hard to recognize but precisely capturing the human extents of happiness, desperation, anger, and the entire spectrum of other feelings.

It is profoundly remarkable that Eisner created these works decades before comics were taken as anything but a mindless paper filler. Reading Life, in Pictures has some of the qualities of gazing at the paintings of the masters: that impression of awe engendered by the sui generis.

Life, in Pictures is an invaluable artifact in the birth of the graphic novel medium and still a high point in the comic catalogue. As such, it deserves purchasing by any true fans of the genre and, truthfully, anyone concerned in the development of autochthonous American art. Bedtime reading, though, it is not.

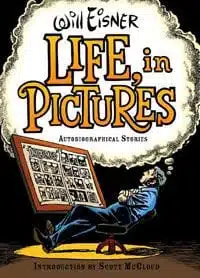

Rather, this collection deserves to be read with all the careful approach of engaging a holocaust memoir and the scholastic-critical attunement of one in a museum. Word of advice: plan in advance some fun activities to execute upon the completion of your trek through Eisner’s anthology. Else, you may find yourself staring frigidly at the cerebral cover of the book for hours.

Author’s note on the rating: Although much of the review focuses on the harshness of the reoccurring themes, it should be noted that Eisner never wrote these stories to be grouped together. It would be sinful to give these works anything less than an “8” because of the by-products of posthumous editorial decision.