Imagine finding out that you’ve been mispronouncing your own name your whole life.

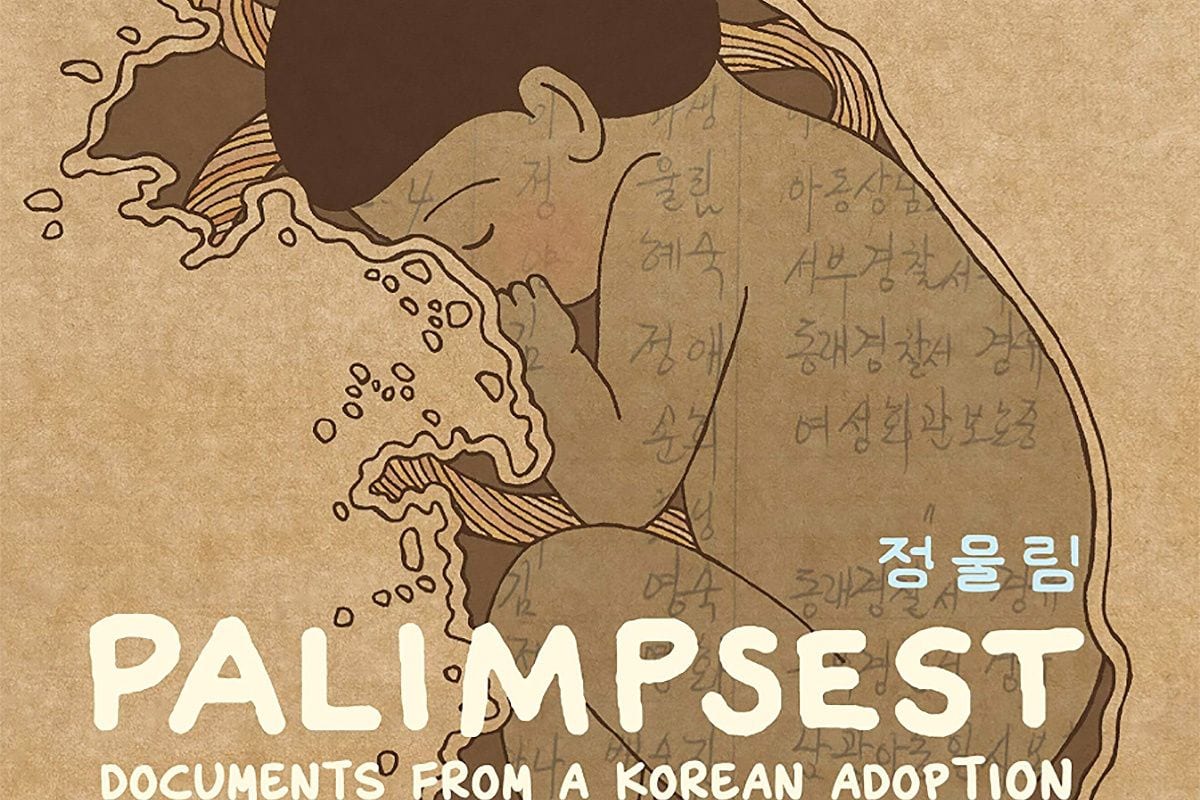

Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, author and artist of the graphic memoir Palimpsest, received her first and last names when she was adopted by a Swedish couple as a baby. Her middle name was given to her by her birth mother in Korea. It means “forest echo,”, and when she heard it pronounced “Oolim” for the first time over the phone, she realized it wasn’t “harsh and ugly” at all.

It probably helped that it was her sobbing birth mother saying it during their very first long-distance conversation. Sjöblom had spent her childhood and most of her adult life believing the false information fabricated by the organizations that arranged her adoption. It was only after she had her own child that she began searching for the truth.

Sjöblom’s subtitle is significant. Though Palimpsest is unquestionably a graphic memoir, “Documents from” connotes an atypical approach and aesthetic to the genre. The opening two pages feature a complete letter from a government official whom the author’s adopted father contacted for more information about her adoption. Though verbose, the official provides remarkably little.

Sjöblom includes several other similarly full- and partial-page letters throughout her narrative. Most are reformatted and typeset in the same font as Sjöblom’s narration, emphasizing that they are not the actual documents but recreations. She redraws other documents too, including an online form for “Post-adoption Services” and a hand-printed letter that she wrote herself early in her quest to find her birth mother.

One page also includes actual photocopied reproductions of two sheets from her adoption file. The sheets are critical because they contain contradictions that serve as the first clues in Sjöblom’s detective-like search. The sheets also provide the literal background of the memoir: the yellow-gray of the paper is the same yellow-gray that Sjöblom uses as the background of every panel, layering her cartoon figures and text boxes over it. Though her colors vary, all are grounded and unified in a palate inspired by those two life-changing pieces of paper.

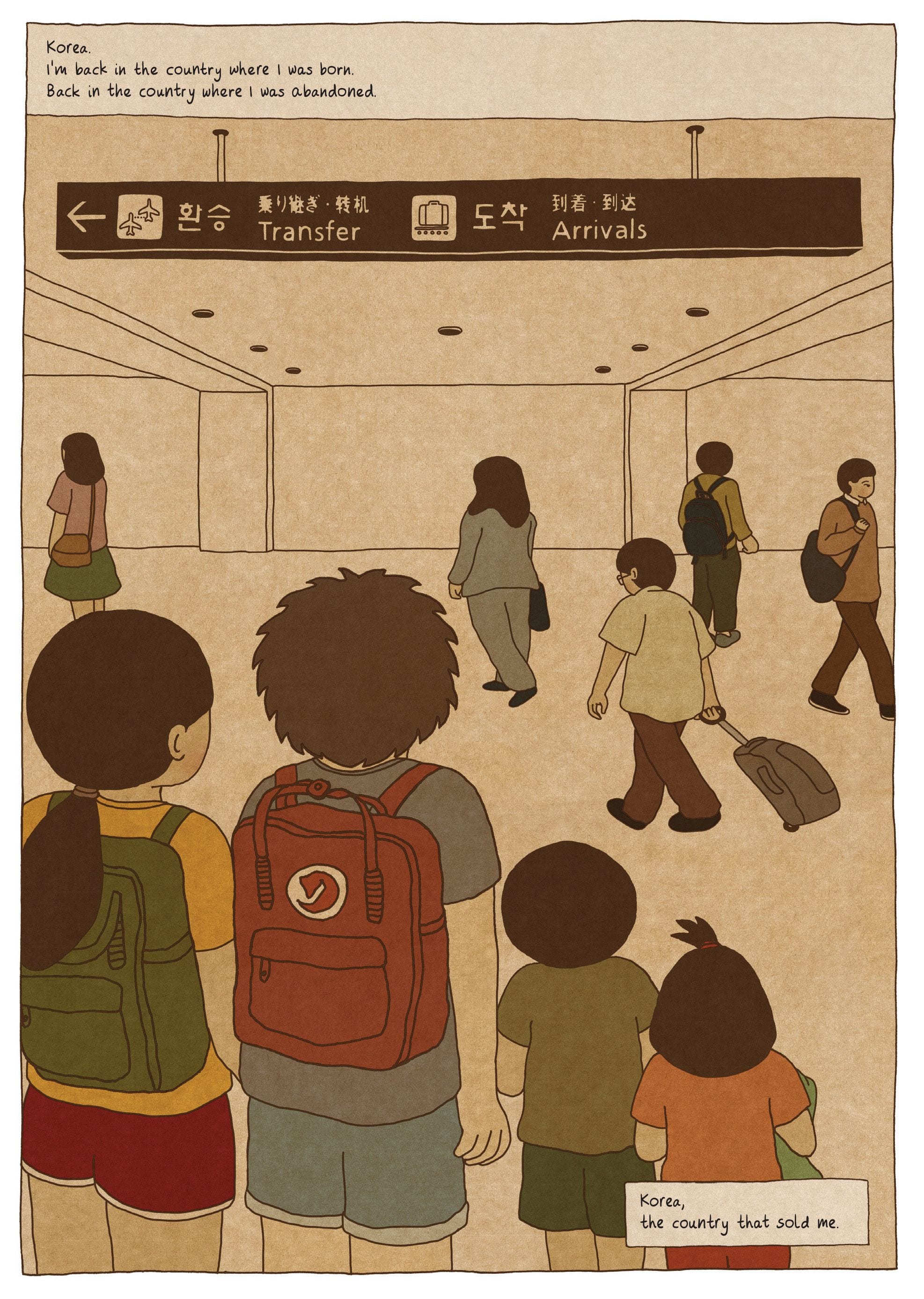

The second half of her subtitle, “A Korean Adoption”, is equally revealing. While accurately describing her subject matter, Sjöblom’s use of the article “A” rather than the personal pronoun “My” distances her from her own story. She prefers plural pronouns, writing: “It’s no wonder we adoptees forget that we were ever born” and “Many of us actually believe our lives started with a flight.”

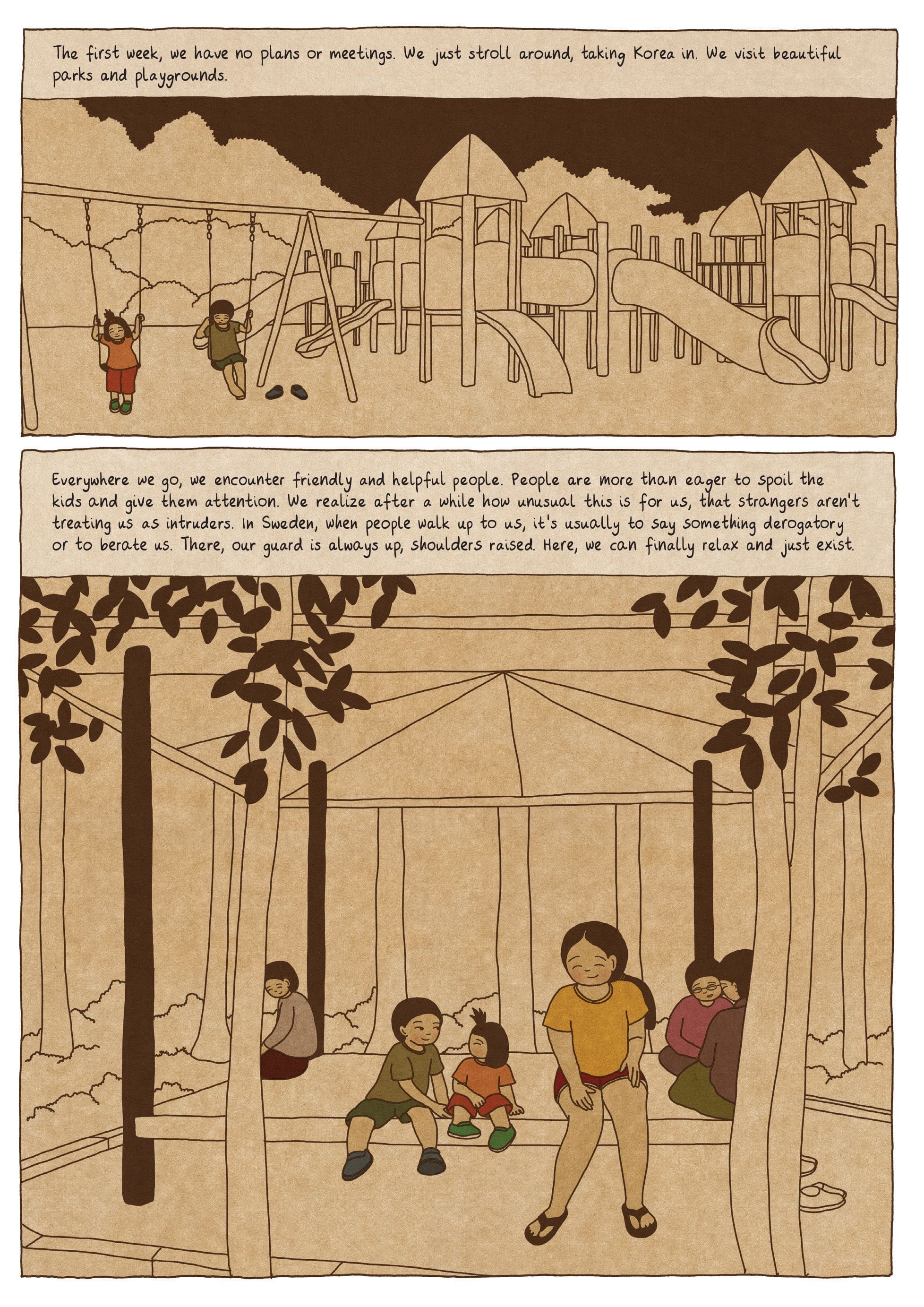

While this is atypical of any memoir, Palimpsest is visually unlike most graphic memoirs. Though images accompany most of the text, their image-text relationship is sometimes purposely inexact. A woman leans over a child in bed with the talk balloon: “It was as if you’d been away on a trip and then came back to us.”

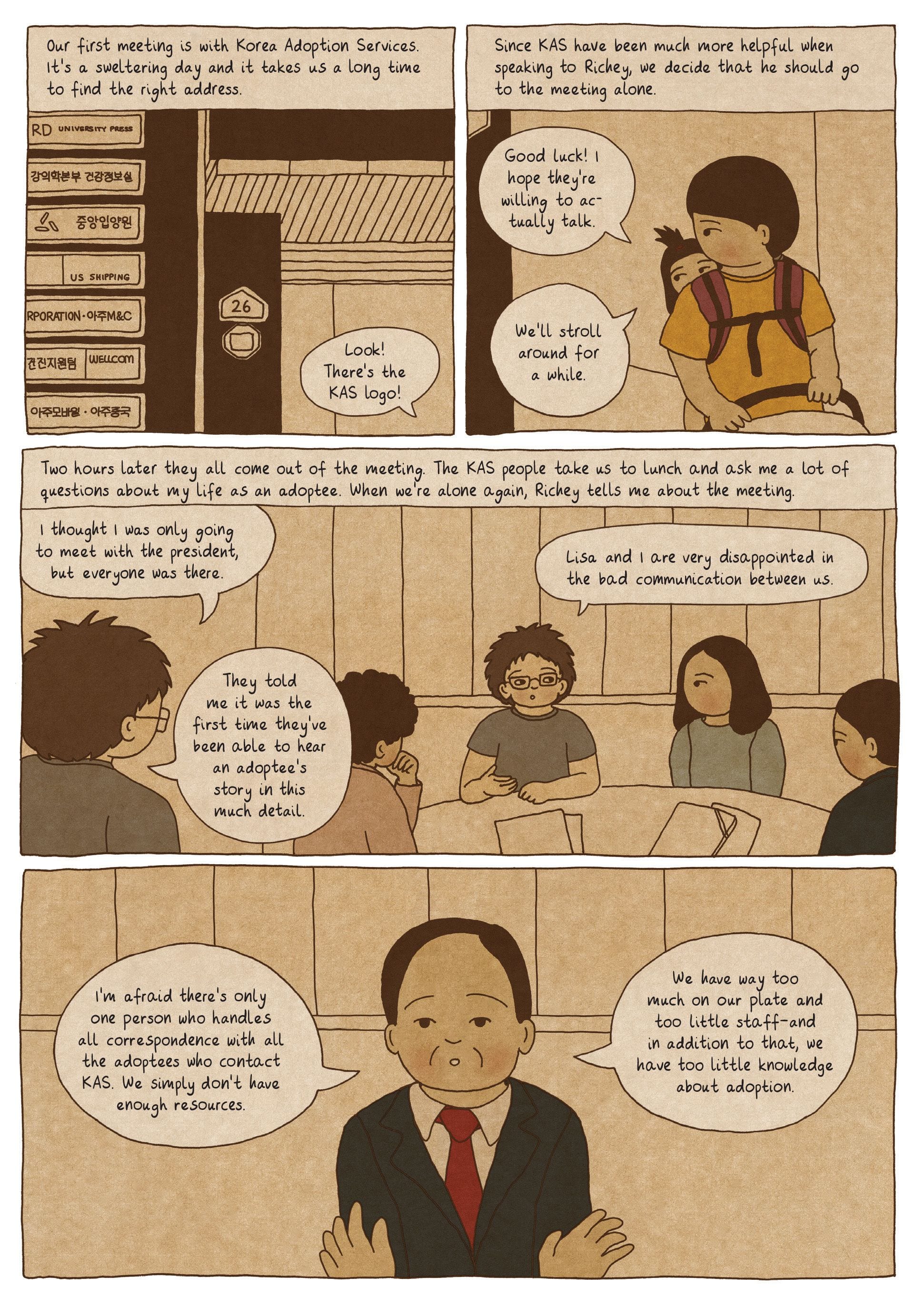

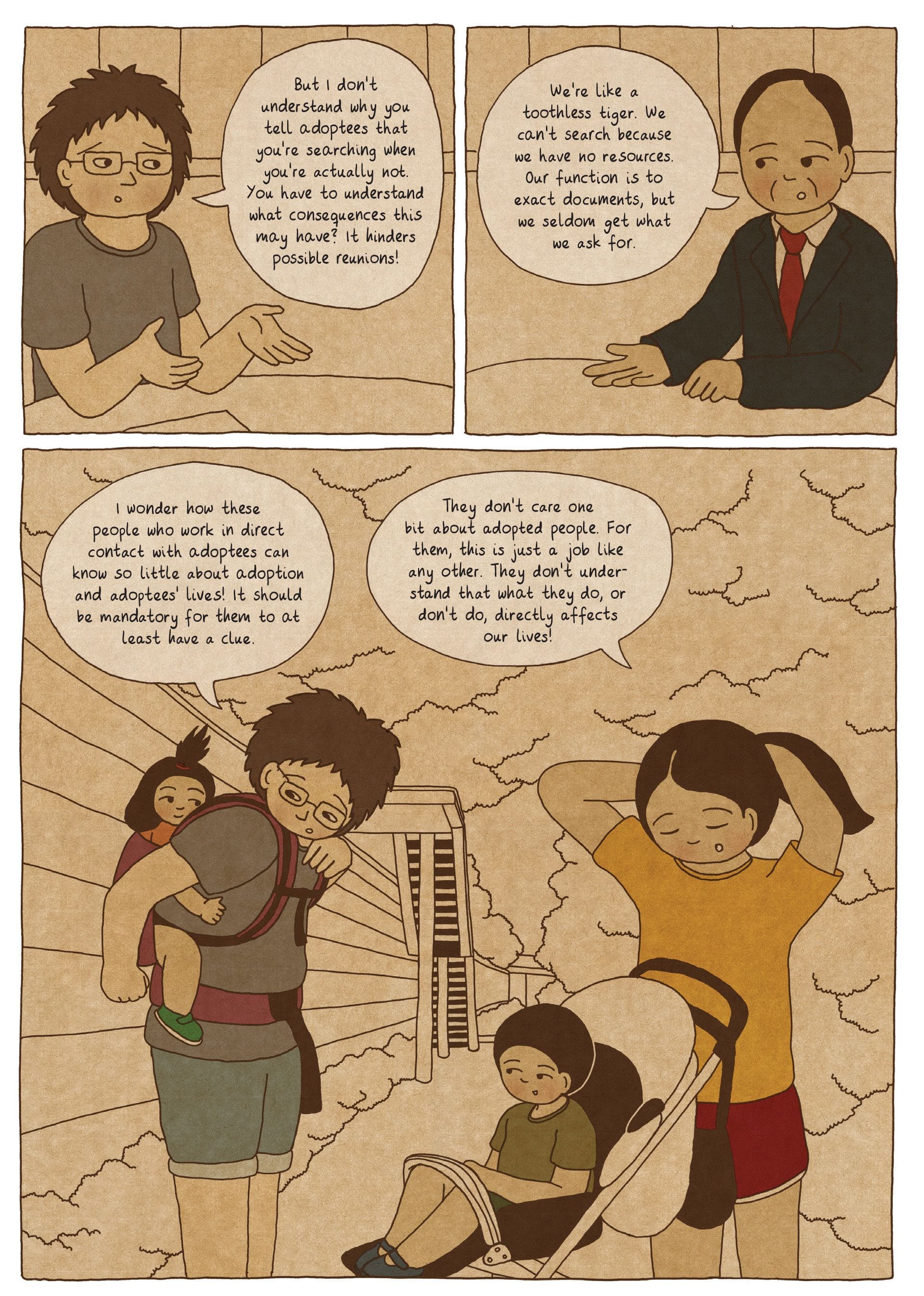

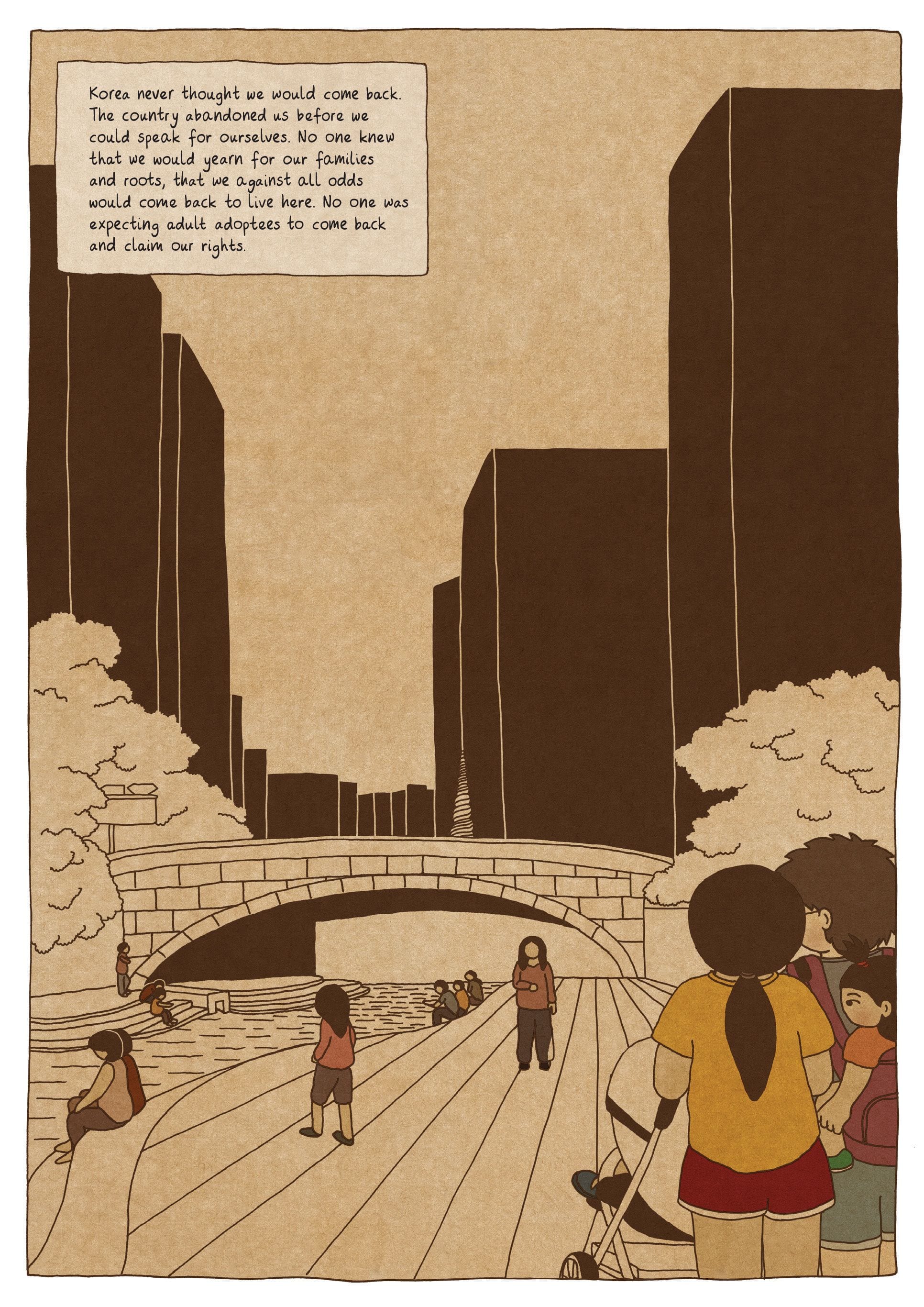

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

On my first read, I assumed the child was Sjöblom and the woman her adoptive mother, but then I noticed that other images of what could be the same mother didn’t entirely match, especially in hair color. Sjöblom’s cartoon style is particularly stripped-down, making all of her characters generically similar, but the ambiguity seems intentional, as if Sjöblom is drawing “A” adoptive mother but not necessarily her own.

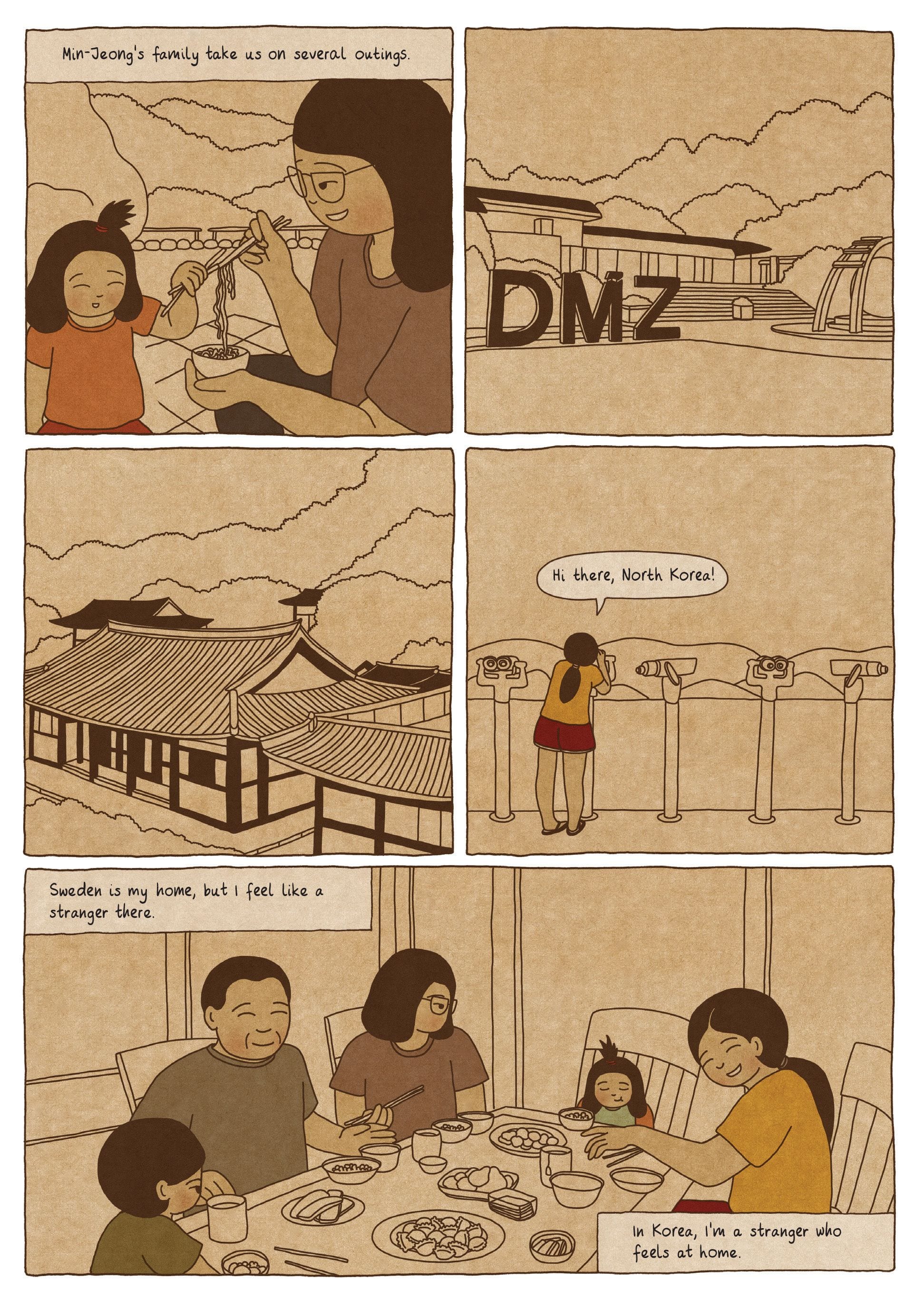

Those distancing and reading effects continue. Though she introduces her husband visually on page 17, she doesn’t refer to him by name until page 41: “Rickey googles the address he finds in my Social Study, but he keeps coming back to a place which seems to be the City Hall.” A map appears below the captioned narration and a talk balloon pointing out of frame: “When I search for the address of the hospital I only end up at City Hall.” Since the previous image is of Rickey seated at a computer, if the narration were removed, little if any information would be lost. This matches Sjöblom’s generally word-heavy approach.

While I prefer a visual style that emphasizes images as the main force driving a narrative, Sjöblom’s emphasis on expository prose matches her purpose. Five of the six authors quoted on the back and inside covers have expertise in adoption, Asian studies, or both, while only one is a comics artist. Again, the subtitle, “Documents from a Korean Adoption”, establishes her priorities. Had she placed “graphic memoir” in the subtitle instead, readers might expect a work more deeply invested in its visual form.

Still, I wonder about the opportunities of the title. A palimpsest, as Sjöblom’s epigraph explains, is a document “in which writing has been removed and covered or replaced by new writing.” This is an excellent metaphor for adoption generally and especially the literally erased and rewritten documents that define many Korean adoptions. But it is also a visual metaphor.

Sjöblom develops it in her cover image that beautifully features a child in utero, seemingly gestating inside the paper of the cover, with a thin layer of untranslated Korean words crosshatching the baby’s body. One page of the memoir also includes a photocopied document with talk balloons over it. The interior of the balloons are opaque, so the words of the document and its text are not visible through them, but the page is still a palimpsest. Given the importance of palimpsests both literally and metaphorically to the memoir, Sjöblom might have explored the visual form beyond these two instances.

But Sjöblom does explore the minute details of her search for and reunion with her birth mother, moving from doctored documents to live phone conversations to physical reunions in the country she left when she was far too young to remember. While anyone interested in adoption should appreciate the memoir, it is particularly revealing of the abuses of the transnational adoption system that not only obscured her history when she was a child, but continued to resist her attempts to find the truth as an adult.

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)

(Courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly)