Doc Mitchell’s a good guy. There I was: kneeling, hands tied, facing down the barrel of a gun above a shallow grave in the middle of the Mojave. My killer’s a classy guy — he looks a bit like a sentient Ken doll — and he apologizes before pulling the trigger. Flash of white, cut to black. Doc’s sitting across from me. Careful, he says, I’ve been out for a few days. His eyes are dark and his mustache is a wispy white. He looks like a post-apocalyptic version of an old-fashioned country doctor, which is what he is.

This being Fallout: New Vegas, I enter my name, edit my appearance, and choose my stats. I put a bunch of points into speech (as I heard you can defeat the final boss just by talking to him). It’s my first Fallout game, and the possibilities seem endless. I can walk to the bar and trigger the first quest, or I can wander off by myself. I can scrounge for cigarettes in people’s cabinets. I can repair robots. I can befriend robots. I can appoint a robot as sheriff. I can meet people who eat people. I can eat them, too, if I want. I can play the way I want to play, or so I heard.

I also heard you can kill anything and anyone. Mutants, giant bugs, soldiers, shopkeepers: anyone. The kindly old couple tucked away in the small town of Novac? They can die. Pull out your gun and press the trigger. Early on, after I run through the combat tutorial, I go back to Doc’s house. He’s sitting in his chair. The question pops into my head: Can I . . . ? I pop up the targeting system. I cycle between right leg, left arm, torso, head. As the good doctor’s head detaches from his body in gratuitous slow motion, I receive my answer: Yes. Yes I can.

***

I’m a compulsive quicksaver. Savescummer, if you want to be harsh. I played Half-Life 2 in two minute chunks, constantly reloading if a fight was going poorly or if I lost too much health or if I just wanted to try a different approach. I reloaded a quicksave whenever I was spotted in Dishonored, which was often. Same with Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Maybe it’s the perfectionist in me, the inability to deal with failure, no matter how small. Real life doesn’t let you jump back in time whenever you tell a joke that doesn’t land or spill a glass or forget your keys, so why not take advantage of that ability in games?

More to the point, if you can erase all your actions with the press of a button, why not experiment? Why not kill the man who saved your life? Why not throw a grenade into a crowded bar? Why not kill a man, take his clothes, and drape the corpse on his wife’s bed? (She doesn’t react if you stealth kill him, which makes for an odd sight.). If you can, why shouldn’t you?

Fallout: New Vegas doesn’t have an answer to this question. There’s a morality system, sure, but there’s nothing to stop you from doing something horrible and undoing that horror. Plenty of critics have written about the flaws of a binary good/evil morality system in games, but my main criticism is that these systems have nothing to do with my own morality. I can play paragon in my first playthrough and I can play renegade in my second just to see all of the content, to get the most game for my dollar. I don’t choose to play as good or evil because I’m moral or immoral. I play both because I want to see all that there is to see.

***

We now regrettably arrive at the part where I talk about Undertale. Sorry. By the way, if you haven’t read it already, check out Nick Dinicola’s in-depth analysis about the muddiness of Undertale’s ethos of pacifism.)

There’s a great moment in PewDiePie’s playthrough where he meets Flowey after sparing Toriel, the game’s first boss. It’s the first real challenge of the game and the moment when many players commit to either killing every enemy that they come across or sparing them. PewDiePie initially killed Asirel but felt so bad that he reloaded a save and spared her. She tearfully says goodbye, hugs the protagonist, and walks away. Much better than shattering her soul.

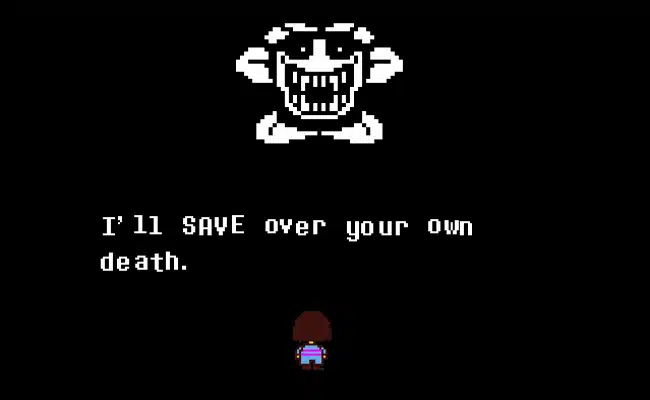

But Undertale is different. Actions have consequences, and they can’t be erased. “Don’t break the fourth wall with me like that,” PewDiePie says, when Flowey confronts him about killing Toriel in another save. “That’s as fucking creepy as fucking shit.”

There are two “true” endings to Undertale: pacifist and no mercy. Pacifist involves refusing to kill anyone. No mercy involves deliberately seeking out and exterminating everyone. Years of gaming conditioned me to have it both ways, to be a good guy the first time around and a monster afterward. I paid for this game, after all, so shouldn’t I try to squeeze out as much value from it as possible?

Undertale says, no, you shouldn’t. You can’t have it both ways. “The victories you earn along one path or the other become hollow: If you try to make peace after you murder everything in a quest for power, the peace you find will be a lie,” writes the author of the Problem Machine blog. “If you go back to destroy the world after saving it, you’re forced to confront how shallow your first quest was, how self-serving the peace you created” (“Undertale: Reflections”, Problem Machine, 9 April 2016).

The way you behave in fictional worlds reflects your moral code in the real world, says Undertale. That’s an uncomfortable thing for a game to suggest. I’m not entirely sure I buy it, but I at least agree with Undertale’s assertion that we should empathize rather than fight, that we should treat other people — even fictional people — with the respect that we ourselves wish to be treated with.

So maybe I should stop quicksaving. Maybe I need to live with my mistakes. Maybe I should try to treat the wasteland as a real place and its citizens as real people. That’s not always easy (the Fallout facial models have always been stuck in the uncanny valley), but it wouldn’t hurt to try. I think Doc would be glad, if he’s not too angry about all the times that I killed him.