Was Walt Whitman gay?

Depends on your definition of “gay”. The word didn’t have anything to do with sexuality during Whitman’s lifetime. The word’s meaning may be anachronistic too. Not that 19th-century men weren’t having sex with each other, but they likely weren’t categorizing themselves along a gay-straight dichotomy. “Bi” would be alien for the same reason.

But whatever your preferred word and definition, the most famous American male poet appears to have had some highly non-platonic feelings for other men, as expressed in his 12-section long poem “Live Oak, with Moss”. Whitman writes in the opening section: “the flames of me, consuming, burning for his love whom I love … my life-long lover”. If you think “love” and “lover” might have non-sexual meanings, the third line is clarifying: “my heart beat happier … for he I love was returned and sleeping by my side”. If “sleeping” still isn’t overt enough, consider how he describes two men departing on a pier: “The one to remain hung on the other’s neck and passionately kissed him—while the one to depart tightly prest the one to remain in his arms”.

So, yeah, Walt was totally gay.

This should matter to poetry fans for a range reasons—not least the new edition of Live Oak, with Moss published by Abrams this spring. This should matter to comics fans for the same reason, since artist Brian Selznick receives equal billing as Whitman’s co-author. Their same-sex collaboration should delight both fanbases.

Whitman started “Live Oak, with Moss” in 1856, not long after self-publishing the first edition of Leaves of Grass. He finished it in 1859 by handwriting the 12 sections into a handmade notebook—which is represented in the Abrams edition in the form of 18 meticulously reassembled color photographs. It’s clear from a glance at Whitman’s ragged script and penciled cross-outs that the notebook was still a work-in-progress. When the individual poems appeared in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, they were revised, divided, and redistributed into a larger sequence.

Live Oak, with Moss not only restores the original poem “cluster” (Whitman’s preferred term) but significantly adds to it. Selznick’s art consists of 56 two-page spreads; 48 precede the poem (which fill only 14 pages), with a coda of eight. In terms of page count, Selznick is by far the primary author. While fans of Selznick’s children’s book collaborations The Invention of Hugo Cabret (Scholastic Press, 2007) and Wonderstruck (Sholastic Press, 2011) (enjoy Bernard Boo’s interview with film producer of Wonderstruck, Christine Vachon, here) should recognize his style, the images may surprise. Eight of them are intensely intimate, colored-pencil close-ups of ambiguously cropped nude bodies in sexual contact. They are not pornographic. Selznick draws no genitalia. He draws no faces, either. The most distinguishable features are fingers and brightly red nipples. The dark folds and sloping expanses of meticulously cross-hatched skin are landscape-like, bordering on abstraction.

If you worry that the great American bard is being resurrected in an anachronistically sexualized context, look at the first edition of his Leaves of Grass. I mean literally look at it: Whitman’s unattributed portrait appears as the frontispiece. It’s not just that his pose is cocksure (fist on hip, hat at a jaunty angle), but his actual cock, albeit clothed, is prominent. Whitman had the artist add more detail to the crotch. (WhitmanArchive.org)

According to scholar Karen Karbiener, whose 30-page afterword provides much appreciated biographical context, Whitman modeled “Live Oak, with Moss” after Shakespeare, whom he considered a “handsome and well-shaped man.” He was especially taken by the sonnets and their subject matter of a “beautiful young man so passionately treated” and “ancient Greek friendship”. He was sure Shakespeare had been in love with the Earl of Southampton. Karbiener is sure Whitman was a patron of New York’s Pfaff’s beer cellar, “what may have been America’s first gay bar.”

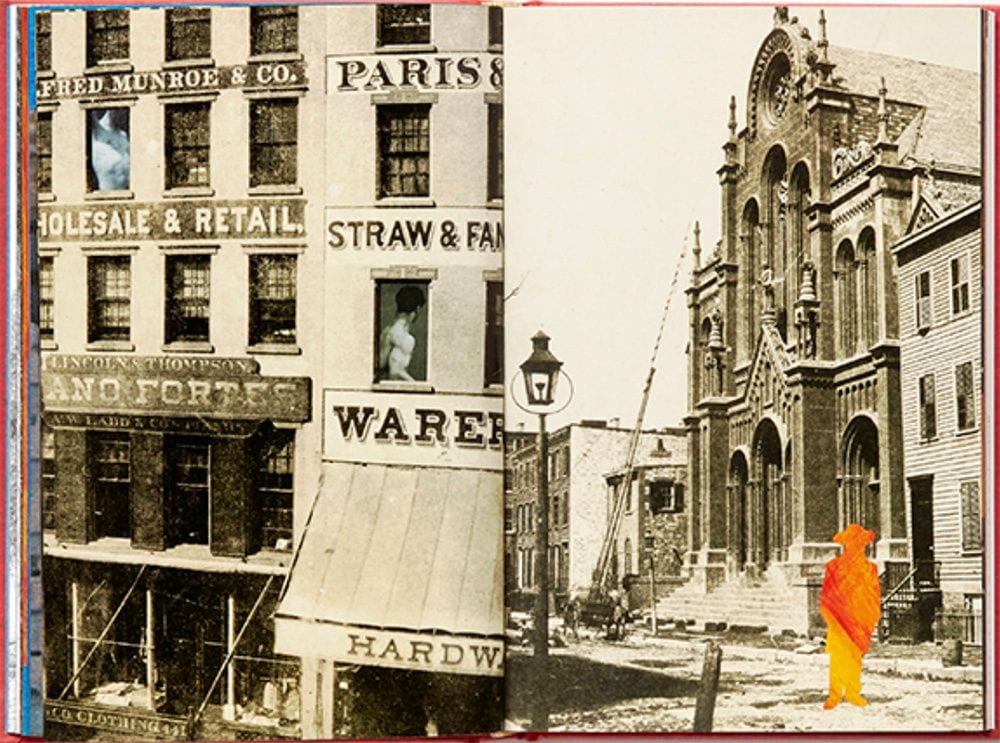

Selznick’s art includes six adapted photographs of mid-century New York streets and buildings, with black and white male nudes collaged in their windows. Whitman’s flame-filled silhouette stands apart in page corners, until the urban background transforms to black and then a star-speckled sky. Whitman and a period nude move from their opposite corners, enlarging into sprinting poses before meeting at the page fold and erupting, nova-like.

But is Live Oak, with Moss a comic?

Depends on your definition of “comic”. Whitman died in 1892, roughly the year the word began to refer to cartoon images in new newspaper sections and humor magazines. By the end of that decade, comics included panels, gutters, talk balloons, and other conventions associated with the form, but entirely missing from Selznick’s art. So if you’re expecting a caricatural version of Whitman declaiming his poetry in expressive fonts and word containers divided into a sequence of panels that illustrate their content like movie storyboards—this is not that. Selznick isn’t adapting Whitman into a visual narrative. He doesn’t even incorporate Whitman’s words into is art. The two modes, language and image, never combine, never even appear on facing pages. They are distant lovers, as divided as Whitman and Selznick are as collaborators.

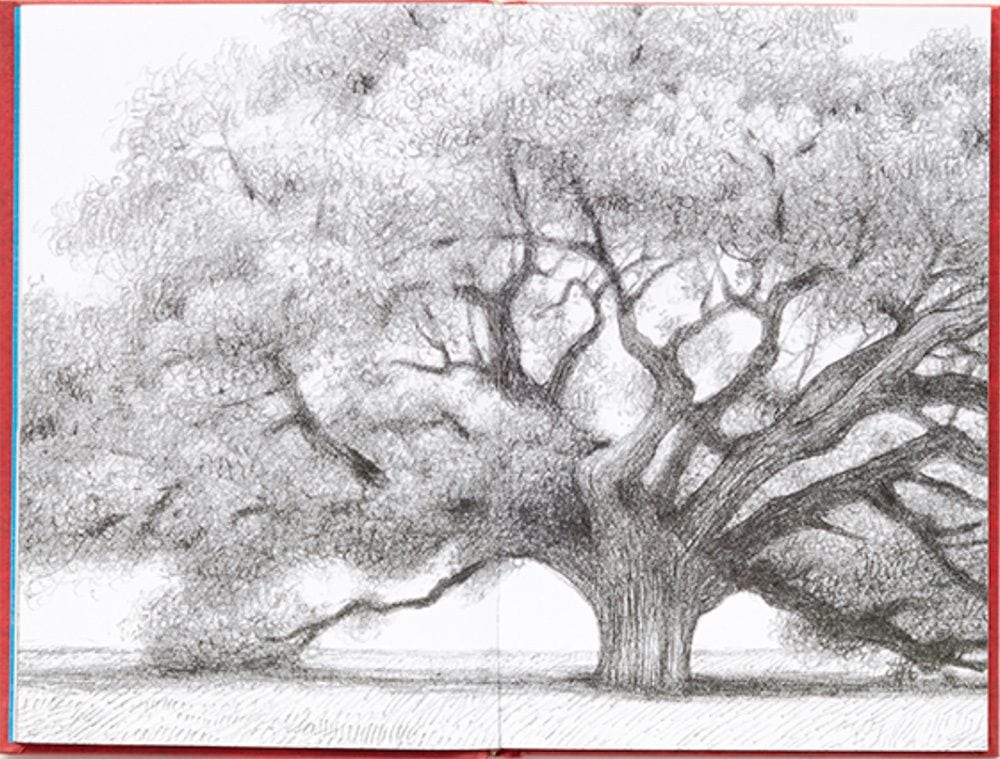

Still, there’s a reason Abrams named its imprint “ComicArts”. Selznick responds to Whitman’s numbered but non-narratively ordered cluster by developing its verbal imagery into tightly sequenced and linked visual progressions. It opens with an incremental movement toward and then into an oak, revealing a world of dueling flame and water beneath and beyond its bark. Other images, such as the concluding pages of pure red and white configurations that resolve into impossibly red branches on an impossibly white background, would be at home in the Andrei Molotiu’s anthology, Abstract Comics (Fantagraphics, 2009).

Another sequence uses its white space to depict snow mounting page-by-page inside a rustic cabin, until the snow banks become the absolute whiteness of the page itself, and so the backdrop for the black ink of Whitman’s words. The entire sequence ends with the same black and white rendering of an oak in full foliage that opens the book. All these wordless images meditate on Whitman’s poetry, suggesting the internal explorations and struggles layered in the poet’s expansive language.

So, yeah, Live Oak, with Moss is totally a comic. One of the best I’ve read this year.