By the time the year 2000 arrived, the music scene in America seemed uninspired following the disastrous aftermath of Woodstock in ’99 — a period dominated by nu metal, ska punk, and boy bands. The alternative rock revolution that ushered in by Nirvana only ten years earlier seemed like a distant memory against the popularity of such acts as Limp Bizkit, Korn, Backstreet Boys, and O-Town. While Britpop provided a temporary spark, it didn’t have much of a long-lasting impact here. For fans of alternative rock, the future at the time seemed both uncertain and unpromising.

But then in 2001, a scruffy-looking quintet from New York City called the Strokes made waves not only locally but also nationally and overseas with their debut album Is This It. Gritty, exhilarating, and sexy, the band’s brand of retro rock ‘n’ roll recalled the DIY fervor and excitement of ’70s punk rock. The Strokes’ popularity opened the floodgates for a new crop of New York City-based bands, including Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, Vampire Weekend, LCD Soundsystem, the National, and TV on the Radio. From 2001 to 2011 those bands, as well as those outside of New York like the White Stripes, the Killers, and Kings of Leon, restored one faith’s in rock ‘n’ roll again. The fact that nearly all of them are still making music today is a testament to their art and perseverance.

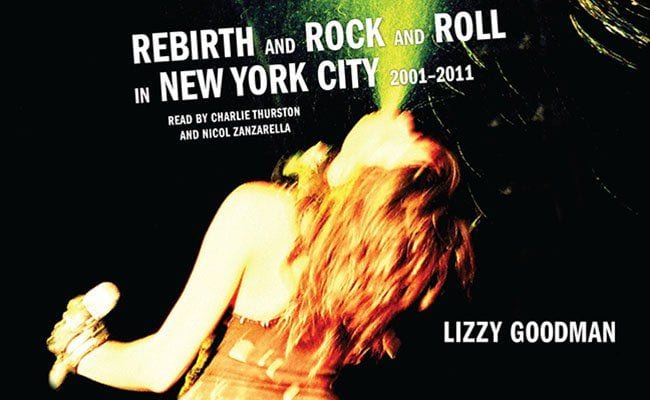

Author Lizzy Goodman lived through that period in the Big Apple after she moved from Albuquerque, Mexico, circa 1999. There she befriended a reluctant restaurant employee and aspiring musician named Nick Valensi from a then-unknown band called the Strokes. Almost 20 years later, Goodman documents that era in a new book called Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011. An oral history, Meet Me in the Bathroom features interviews with members of those aforementioned bands as well as journalists and tastemakers who recall that period with both frankness and fondness. While some of the stories revel in the wild and outrageous, they also speak of these bands’ determination and perseverance amid changing times: from the shock of 9/11, to the decline of the traditional music industry, and the growth of Brooklyn, New York, as a creative and hipster hub.

Goodman — whose works has appeared in Rolling Stone, ELLE, and The New York Times — spoke with PopMatters about writing Meet Me in the Bathroom, and why this period stands with other previous music-defining eras such as punk and hip-hop.

Lizzy Goodman (Photo credit: Kaita Temkin)

What inspired you to write Meet Me in the Bathroom?

The conception of the book began basically where it ends. The conclusion of the book is the dovetailing of the Strokes and LCD Soundsystem playing Madison Square Garden [in 2011] — these two major characters of that era in New York City music colliding at one of the most legendary venues. I went to both of those shows and I had this sort of distinct feeling during the two-day span of those shows that “Wow, something’s finishing.” It just felt like a shift in the New York rock story that I’ve been covering and living to some extent. It was the first moment when I realized there was a bookend to some part of this story, and that was the beginning of thinking about how to write about it.

Having gone to see very early Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and Interpol shows, and having been in college when all those bands were coming up, it sort of felt like my own story as a journalist and a young person in New York City who was there. It was like ‘Okay, this is a chunk of time. This is a decade. It’s 2011, and I’m standing here watching these bands that I used to see play in rehearsal spaces [and now] the Strokes are playing Madison Square Garden. This is the period of time that a full story has happened in, and so I’m going to try to capture that.

How much was Legs McNeill and Gillian McCain’s ’70s punk oral history book, Please Kill Me, an influence for Meet Me in the Bathroom?

Please Kill Me is the bible. If you want to write an oral history of any length, it’s the ultimate. It’s fair to say that this book would not exist had I not read that book. Well before I had any idea I would be a journalist or be writing an oral history of my own period of time in New York, that book was an influence on my relationship with New York City and music, and introduced me to bands I didn’t know about. It’s one of the most seminal works of literature in my own life as a journalist and writer. When I was starting to assemble my own attempt to tell this story, one of the reasons I knew it could be done this way is because Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain had done it.

Brooklyn, especially the Williamsburg section of the borough, became the creative epicenter for alt-rock bands like Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the National, and TV on the Radio. Could you elaborate on that?

Brooklyn has become a stand-in brand kind of name for New York cool and New York in general. At the beginning of one of my interviews — I think it was with James Murphy — I was broaching the subject of Brooklyn and this idea of this place that was just a bunch of shitty houses in Williamsburg, and now it’s this concept of cool that the world was attempting to emulate. He was like, “Oh yeah, that’s our fault” (laughs). This is the story of gentrification, the age-old story of how art happens in a space where it’s possible to be born. I think that’s what Brooklyn offered people, a place where there was enough nothing going on to make people frustrated and also give them the opportunity to fill it with something.

As these alternative rock bands were emerging, the business of traditional music industry was declining, fueled by the popularity of Napster.

These artists came up during a time when there was the decline of the infrastructure that used to support rock ‘n’ roll. It was a time of a lot of change and a lot of the artists covered in the book really bridged the gap between those two worlds. In the book, Interpol’s first record [2002’s Turn on the Bright Lights] comes out in this 20th century music industry world and even though they’re on an indie label, that has a certain identity that comes with it, and there’s a culture around that. By the time Antics, their second record comes out, it’s leaked three months early and it’s like, “You’re in a new world.” We’re talking about almost no time passing.

The rate of adjustment that artists had to go through during that period of time, in terms of figuring out what the business is versus what it had been, is really dramatic and also really fascinating. It goes without saying almost all of those bands would have sold shitloads of records in a previous era. They have not for the most part been benefited by the decline of the system that used to exist. [But] you wouldn’t have Vampire Weekend and the sound that Vampire Weekend invented if those dudes weren’t able to access Kate Bush, Public Enemy, and Paul Simon on Napster in their basements when they were 15. So it changed the kinds of artists we have and what we hear.

The Strokes dominate the book regarding leading the rock revolution from that era. And you knew the band’s guitarist Nick Valensi before the Strokes finally broke through.

The Strokes synthesized all of the things that would come to define this era and allow it to be disseminated throughout the world as reborn coolness, this sense of aloofness. They’re all really handsome, good looking, seem-to-be bad-ass urban creatures. The aesthetics, the sound, the aura that they were able to carry… they were able to take the thing that a lot of people were doing and they just did it better.

It felt at the time so obvious: that elegant simplicity, like “Oh duh, punk rock.” Beautiful, accessible, sexy, dirty, pretty punk rock. The directness of the appeal of what they were making was so complete. A lot of their peers say this in the book, they were just the coolest and they were the kings. That’s why their story is so important and part of the scaffolding in telling this entire story. You couldn’t do it without them.

When I first met Nick, it was the summer of 1999. I was in school in Philadelphia and came to the city and got this job at a restaurant, and Nick just graduated from high school and was working at this restaurant and we were bored summer city kids trying to get out of work together. He was good at that, and he was teaching me the ways of avoiding work.

We stayed in touch and stayed friends as I went back to school and he kept up with the band, obviously. He gave me a copy of his band’s stuff. It was a little demo CD and it had a monkey on the cover and it just said “The Strokes” in Microsoft Word font. It was very lo-fi. They really weren’t what they became, it was just my friend’s band. [Later] I remember seeing the UK version of Is This It on display at Virgin Megastore [in New York City], and being like, “Oh my God, Wait a minute. Maybe it was okay for him to drop out of college. This is so cool.” It took me a while to realize what the hell was going on.

Through all the interviews you’ve conducted, what was perhaps the most fascinating to you?

For me personally the DFA [Records] stuff. James [Murphy] and Tim [Goldsworthy, the co-founders of DFA] — they were kind of the big arm of the story that I didn’t know very much about and also didn’t know any of the players. I was only into LCD Soundsystem much later. It was going back and researching a story that I was living but didn’t know about. Getting into that part of the story was really personally gratifying and fascinating because it was unfolding in front of me.

[James and Tim] are the most amusing sensitive inspiring characters that I’ve ever had the pleasure of interviewing because they are so talented but simultaneously so committed to the life of a New York artist. They were willing to go there about everything they’ve been through. James and Tim, in particular — that relationship was fraught obviously, really intimate and then really destructive in some ways. I really felt inspired their willingness to talk about all the stuff they’ve gone through as a team, making this amazing work.

New York City rock really went beyond the Big Apple, but also nationwide and overseas, as indicated by your interviews with such acts as Kings of Leon, the Killers, and Jack White.

I probably had quoted almost 100 percent of my sources as saying none of this would have happened without the Strokes. Whether they were fans of the Strokes or not, their success opened up all these doors. If you played guitar and were in a band and you were successful in America and England from 2001 on, it’s because of New York City and because of what was happening there. Whether you are the Vines in Australia, [the Killers’] Brandon Flowers working as a bellhop in Las Vegas, or Caleb and Nathan [Followill of Kings of Leon] writing country songs that are too dirty in Nashville for people to appreciate, there’s this sense of permission that was unleashed by the Strokes success.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

How would you compare this era with previous ones like ’70s punk, ’80s hip-hop, and ’90s grunge? Do you think the rock ‘n’ roll revival period of 2001-2011 stands up?

No era repeats itself. Each of the eras you named is distinct for its own reason. What they all have in common is a sense of right band, right sound, right cultural moment. It has to connect to something broader in the culture that people are feeling, and then this ‘X’ factor of why all these things synthesized and matter. I feel really sure that the era I cover in this book is the latest version of that thing we’re talking about: where a generation looking for something collided with the right sound and the right band to present it. And magic, poof, that’s what happened.

For me as a documentarian, I definitely see this as one of the eras that stands out as an important chunk that reveals a lot about where we are as a culture: the rise of the Internet, post 9/11 New York City, the changing of the century — it’s a lot of transition being documented and channeled by people in leather jackets onstage and then later people not in leather jackets onstage (laughs). I think it stands up.

So how did the title of Meet Me in the Bathroom come about?

It’s a Strokes song [from the album Room on Fire]. I think it gets right to the point of the story. One of the things Marc [Spitz, the late music journalist] said to me once in a conversation and I ended up writing and putting it on my bulletin board: “Never stray too far from the bar.” The point of that was there are so many big scenes in the book — 9/11, downloading, and the gentrification issue are huge — but all of those things have to come out from the sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll story. It was important for those scenes to be a part of those bands’ stories and never stray too far from the bar.

“Meet Me in the Bathroom” to me feels like that. It’s a dirty idea. “What are you doing in the bathroom?” “Ooh drugs, ooh sex.” But there’s also something innocent about it. You don’t really know what you are being invited to participate in said bathroom. That’s how I felt about the book. It’s dirty, fun, loose, and young — but also sad, dark, and big.

What do you hope people will come away from both the book and the music that it covers?

I think for people who are reading the book right now and who know this era, the most gratifying thing is that it brings them back to this period of time. For those who were there, I hope it feels familiar in a nice, positive way. And for those who weren’t, it gives them a sense of participation in this really amazing time that has passed, but is still also influencing the culture we are living in. If people who didn’t know it start to feel it, and people who did know it feel it again, then that’s victory.