There is a pervasive sense of despair and futility shrouding Lucrecia Martel’s Zama (2017), an adaptation of Antonio Di Benedetto’s 1956 novel. Whilst it is a re-affirmation of the Argentine director’s filmmaking prowess, an accomplished character study beneath a simple narrative and aesthetic form, in equal measure it reaffirms that spiritual connection between a piece of art and its audience. “When I read the book I identified with the character who was experiencing a great deal of frustration, which was at a particular moment I myself was dealing with the frustration of not being able to complete an adaptation of the comic book El Eternauta [Héctor Germán,1957-59]” explains Martel.

Zama tells the story of Don Diego de Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho), an officer of the Spanish Crown, born in South America, who awaits a letter from the King granting him a transfer from Asunción to Bueno Aires. Trapped in this delicate situation, Zama is forced to submissively accept every task entrusted to him by the successive Governors who come and go as he stays behind. After years of waiting and with hope eventually lost, he joins a party of soldiers that go after a dangerous bandit.

Zama premiered at the 2017 Venice Film Festival, Martel’s first film in ten years following La Mujer sin Cabeza (The Headless Woman, 2007), which outside of her documentary film work was preceded by La Niña Santa (The Holy Girl, 2004) and La Ciénaga (The Swamp, 2001). In conversation with PopMatters in August of 2017 at the BFI London Film Festival (published here for its UK theatrical release), Martel discusses the ability of art to counter inequality and the influence of science on narrative structures. She also reflects on the absurdity of adaptation within film and opera, and why film should not be a story.

Why filmmaking as a means of creative expression?

I have always loved making plans and lists of things to do; places to visit and to discover; people to know and to meet, and conversations to have, and film opens the door to many of those. So working in film, for example, brought me here [London] and it has allowed me to travel around the world, and it is similar to the experience travellers had in the 19th-century.

The cinematic art form is one of connection, which serves an important role in our divisive contemporary world. Whilst governments and corporations create borders and divisions, cinema is a unifying space.

Yes, exactly! So I think the film has that possibility, and by basing films on people in specific places, it enables us to transcend this idea that the world is divided. This is an obvious statement of fact that the closer you get to a group of people, the closer you get to being able to understand people.

One of the great responsibilities that this role of the traveller has is that we live in a world where we are on the side of the privileged, and all the configuration of cities and all the benefits fall on us; they don’t fall on all their citizens equally. This is important because we all talk about democracy as homogenous, and when we talk about the English and the Argentines, it’s as though one thing means the same for all of them. And now it’s perhaps not even a conscious thing anymore, and we overlook the inequality and injustice of the complexity of those differences. Film is a wonderful medium, as is literature and theatre as a way of subverting that act of turning a blind eye.

In Zama, the emotional and character complexity exists beneath the simplicity of its form – the placement and use of the camera are not overly dramatic or complicated. In your opinion, does a simple or stillness of form compel an audience to be active in looking beneath the surface to explore the underlying complexity?

I think this is an inevitable consequence when a narrative is not based on the plot, but on other aspects. For me, plot was always a pretext for organising, and the objectives you have in a film are always well outside the plot. When the link between cause and effect is not very strong, the viewer necessarily starts to focus in on other things, and picks up on more of those. And finally, if a viewer gives in to being more attentive and picks up on those details, then they will enjoy the process, but if one resists that, then they will absolutely hate the film.

One’s relationship to film or more broadly speaking art, is an ever-changing one. There are moments in which we will individually experience an awakening, discovering an appreciation for an individual work, artist or type of storytelling that was perhaps previously lost on us. As we develop an ear or an eye for art, so we grow into it, developing that relationship.

For many centuries we have been dominated by a form of narrative that has a lot to do with mechanical physics; a rigid way of looking at this relationship of cause and effect. But now, all of these scientific paradigms have permeated into society very deeply, which have changed since the start of the twentieth century with discoveries in microphysics, revealing other narrative possibilities. And I think this is a process of change that is happening now, where most notably the narrative industry in the US is balking against and trying to stop this from happening; most notably with the series. So these series’ have returned to a much more rigid form of seeing narrative, albeit with a great deal of a mastery of ability and intellect. So I see the series as a very conservative thing, as an attempt to hold on to this market.

On the subject of adaptation, theatre and film director Alex Helfrecht remarked to me: “…you have to be bold and brave, and as you said, shouldn’t be slavishly transliterating the novel. You have to have a strong take on the material, but you have to honour the spirit.”

Firstly, the idea of adapting a novel to film is absurd, and when one adapts a book, what one does is create a means of escape. It’s another thing entirely because a novel puts you in a space like a coal mine, where once you are in the book it is like you are in that mine, in the tunnel and you are entrenched. The film gives you a way out, but you can’t get out by the same path the novel took; you have to find your own. In creating that path all the others we have read about in the novel are helpful, and we will have learned from each of them. This is why these novels are called masterpieces because when we read them they affect us, they teach us something [translator note: Maestro in Spanish means teacher and master, hence why I said masterpiece]. So you have to do what you have learned, not what the teacher has told you. It’s very important, or it’s not that it’s important, because it’s inevitable that you will be faithful to the novel.

I am currently working on an opera, and I think one of the greatest flaws or mistakes with opera is the idea that the music has to be absolutely faithful to the score. This is why opera for anyone other than the most highly knowledgeable is so difficult to penetrate. But any representation of an opera with the view to being faithful will end up failing.

Throughout Zama there’s a comedic presence of the absurdity of the situation, culminating in the music that coincides with the end credits merges comedy with tragedy. But there’s an impression that you are communicating to us in an overt, rather than in a subtle manner.

All of the music in the film had that intention and there were many details that were humorous. If the aim of a film is to show tragedy and to learn from it, which it normally is, if I had made a tragedy I would have been reaffirming this idea of identity. So what I tried to do by not doing that and making it a bit more humorous, was to try to show that it was all a bit absurd. It’s like if someone is reported in the newspapers to have raped a girl, they will say he ruined her life, but the life of a person even through such a horrific act cannot be ruined. So in the end, the discourse of the journalist who says that life is ruined actually undermines that person. It’s like when we see a war film; what film about war is really anti-war? The majority of war films in actual fact are about seeing war as an adventure.

On this subject of learning lessons through storytelling, filmmaker Christoph Behl remarked to me: “You are evolving, and after the film, you are not the same person as you were before.” Do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect to the creative process, and does the experience of watching a film offer the audience a transformative experience?

So why would one make a film? It’s because you’ve seen something that you consider important and worth sharing. And this is why I don’t believe a film should be a story. In a film, one tries to create the conditions that enable one to see something else, and these are conditions around perception, not around the story. So what I want from the spectators of Zama is to be able to share with them that lesson I learned from my process of reading the book. This is why novels being adapted hundreds of times over is so interesting because every individual is going to have a different take on it.

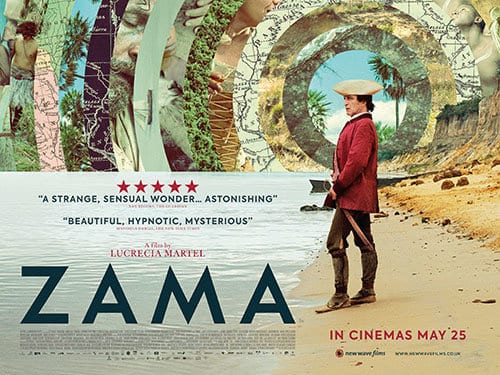

Zama is released theatrically in the UK on 25 May 2018 by New Wave Films and will play at select venues up until the week commencing 15 June. For screening information, click here.

- Lucrecia Martel - IMDb

- Lucrecia Martel - Movies, Bio and Lists on MUBI

- Lucrecia Martel: A Director Who Confounds and Thrills - The New ...

- Antonio Di Benedetto Ace

- An Argentinian Novelist, Out of Oblivion | The Nation

- A Great Writer We Should Know | by J.M. Coetzee | The New York ...

- A Neglected South American Masterpiece | The New Yorker

- Zama Movie Review & Film Summary (2018) | Roger Ebert

- ZAMA (2017) · Official Trailer - YouTube

- New Wave Films - New Releases