It’s no mystery why true crime has always fascinated. It’s a genre that reaches for the absolute apex of human drama with every story: a life is lost, treachery and deceit inevitably occur, a rocky quest for the truth is undertaken. All the necessary elements are present, and the really juicy part is, they’re all fact. Some critics say the genre is undergoing a serious revival right now due to the likes of Serial and The Jinx, as well as improved law enforcement technology and social media. While that’s true, there have always been good examples of the form: 2003’s Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer is one, with its sensitive, moving portrayal of Wuornos; 2004’s The Staircase is another. Among all, however, Netflix’s recent Making a Murderer is by far a standout, not only for its densely woven narrative, but for its far-reaching implications.

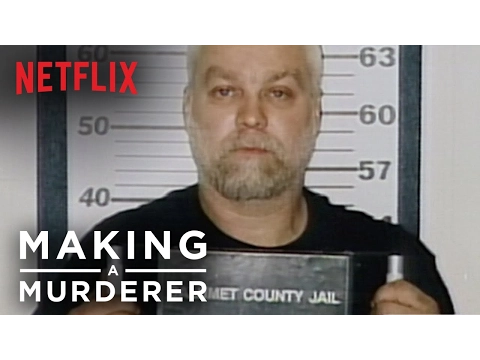

Making a Murderer, chronicles the horrifying tale of Steven Avery, a Wisconsin man who wrongly spent 18 years in prison for attacking a female jogger. Two years after Avery’s 2003 exoneration by DNA, while in the midst of bringing a $36 million lawsuit that would put Manitowoc County’s former sheriff and district attorney personally on the hook for hefty damages, he’s arrested again. This time, as Avery’s lawyer Walt Kelly says, Avery finds himself “rapidly in the most serious of circumstances that any citizen can be in”: he’s accused of murder. The victim is 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach who visited Avery’s house on the day of her disappearance. Sixteen-year-old Brendan Dassey, Avery’s nephew, who has an IQ between 69 and 73, is also arrested. A police frame job is more than suggested, and by the end of the series, it’s hard not to believe.

What immediately makes Making a Murderer great is its unobtrusive style. Unlike Aileen, The Imposter, Cropsey, or even Serial, the only narrative present is an unforced one that’s so seamlessly pieced together you hardly realize you’re watching something that’s been deliberately organized (as all stories must be). Similar to 1996’s Paradise Lost, the documentary about three Arkansas teenagers accused of murdering three children, the filmmakers of Making a Murderer never say a word on camera. Avery and Dassey’s stories unfold through well-placed home videos, photographs, news footage, interviews, and police recordings. Paradise Lost is great in its own right, but what sets Making a Murderer above even that is its sophistication and nuance. While Paradise Lost opens with a Metallica song (a nod to its protagonists) and quickly segues into actual photos of the dead children, Making a Murderer creates more out of less. Nothing grisly’s shown in Making a Murder, except the apparent misconduct by law enforcement.

While the lack of more directed narration makes the story seem purer, offering the viewer enough room to draw their own conclusions, it also doesn’t make things any easier. There’s very little comfort in Making a Murderer, which goes from grim to incredibly grim. The camerawork is accordingly subdued. When Dassey’s mother learns that her son has been found guilty, she runs out of the courthouse and appears to get into an altercation by her car. It’s hard to tell, though, because we hang back on the courthouse steps while other reporters move forward. The camera in Making a Murderer is a stable, brutal witness, and not even a very nosey one. There are no flourishes distracting from the difficult story.

The light that Making a Murderer shines on some pretty dark legal recesses, however, is bigger and brighter. Serial touched on it, especially while interviewing retired detective Jim Tranium; Paradise Lost did too (as do many others of this genre), but the excruciating scope of Making a Murderer resets the bar. The documentary took more than ten years to make, and the events it covers are dated beyond even that, so the result is a prolonged, fastidious look at the repeated failings of our legal system. One of the most agonizing sequences is in episode three, when Dassey “confesses”. It lasts about 14 minutes, with a few bits of commentary interspersed. Fourteen minutes doesn’t sound like a lot, and it isn’t in the context of how long the confession actually took, but it feels like an eternity. Dassey stops and stutters, waiting for clues from the detectives as to what to say, while the viewer writhes in agony, understanding in a way that Dassey doesn’t understand the seriousness of his statements.

One of the principal reasons Avery and Dassey may not have gotten fair trials is due to sensationalistic press coverage. Bits of it are spliced throughout the series, and all of it’s indeed fantastic, with information delivered in polished rapid fire and ominous music swelling in the background. Save for some tempering shots of seemingly capable, alert reporters who ask good questions after each day’s court proceedings, the media is largely portrayed as a nuisance. An interesting problem comes near the end of the series, though, and this is another aspect of Making a Murderer that sets it apart. Special prosecutor Ken Kratz, perhaps the most unlikable person in a vast sea of unlikable people, suddenly finds himself, as Avery was, on the wrong end of the media, when he’s embroiled in a 2010 sexting scandal that ultimately results in his resignation. The temptation’s to revel and gloat in his public ruin, but it doesn’t take long to realize that to do so would be to celebrate the same vehicle that damned Avery.

Making a Murderer is as dark a thing as I’ve ever seen. A fresh outrage is depicted seemingly every second, and it’s impossible not to despair in the face of such powerful corruption. If there is any succor to be found, it’s in knowing that in its exceptional depiction of unprecedented events, Making a Murderer may end up changing our justice system for the better.