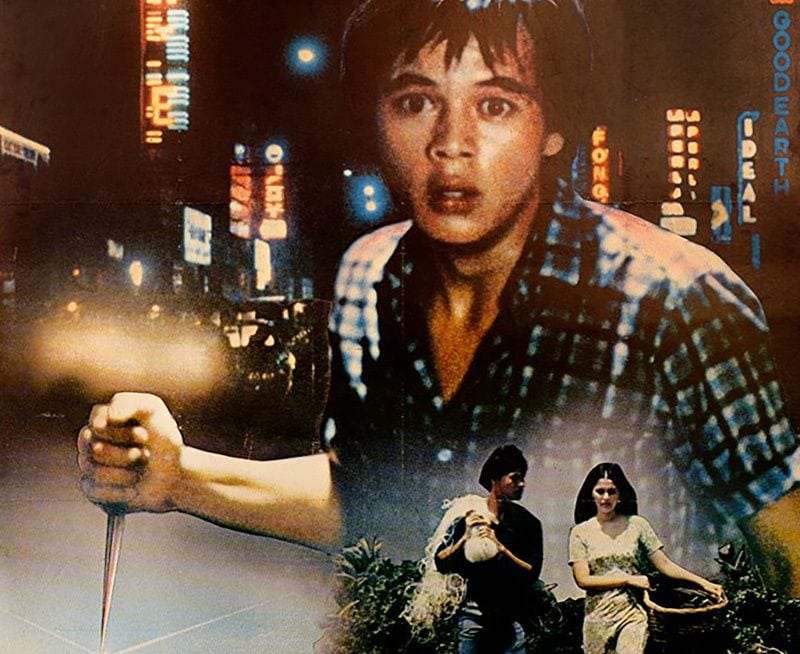

The young Julio Madiaga (Bembol Roco) is a probinciano (provincial) from a small fishing village in the Philippines who now haunts the streets of Manila in search of his lost love, Ligaya Paraiso (Hilda Koronel). He was mugged not long after arriving in the capital city and must now scrape together his subsistence by working a grossly underpaid construction job and, at times, by prostituting himself on the underground gay scene. In the meantime, he hunts for his girlfriend, estranged through circumstance and poverty rather than through will. Julio has traced Ligaya, to the best of his abilities, to the Binondo district, the Chinatown of Manila—the oldest Chinatown in the world, established by the Spanish colonialists in 1594 to contain their migrant subjects—specifically to the corner of Ongpin and Misericordia.

Misericordia (Latin for pity,sympathy) is now Tomás Mapúa Street but was originally named after the Confraternidad del la Santa Misericordia, a religious charitable institution. Ongpin is named for Román Ongpin, a successful and innovative businessman who funded the Katinpunan, a revolutionary Filipino group that fueled the Philippine Revolution that overthrew 333 years of Spanish colonial rule in 1898. Any sense of independence was short-lived insofar as the Philippine-American war led to U.S. control of the country until 1946. Ongpin also resisted American rule and was imprisoned from December 1900 to March 1901; he continued to be involved in less overt acts of resistance for the remainder of his life.

This location, this seemingly insignificant intersection, plays an important symbolic role in a film teeming with symbolism and particularly with symbolism pertinent to the history and political climate of the Philippines: Lino Brocka’s 1975 masterpiece, Manila in the Claws of Light (Maynila sa mga kuko ng liwanag). Over and again we find Julio standing at the crossroads of Misericordia and Ongpin, the crossroads of pity and revolt. If pity is the feeling of sorrow inspired by the suffering of others (and at times, as in self-pity, inspired by one’s own suffering), then revolt is the act of rebellion against political encumbrance, against a regime deemed unjust that must be destroyed in the cause of liberation. If sympathy is the resonance of one human soul with another (literally, from the Greek, a “feeling together”), then rebellion is the willful severance of the oppressed from the oppressor, the tearing asunder of a relationship of domination.

On its own, pity is a relatively static emotion. We suffer in resonance with another but that fellow feeling does not necessarily lead to action. For action to ensue, something more than pity must be involved—namely resolve. Indeed, pity is a rather odd emotion insofar as we generally tend to avoid pain but pity is precisely the feeling of pain on behalfof someone else. And yet, pity inspires in us a certain humility and a recognition of our essential sociality. We suffer on behalf of the other because we realize two things: first, their suffering could easily have been ours given slightly different circumstances; second, on the larger level, their suffering truly is ours. Insofar as we are inherently social animals (humans tend not to function well in true isolation), our emotions are not purely private; there is a social aspect to emotion. If one person suffers, on a very real level, we all suffer.

Revolt derives from emotion but is not, in itself, an emotion. It is necessarily dynamic, an active force of change in the world, change that the revolutionary expects will alter the currently operative political landscape for the better. Revolution depends upon the extirpation of the old ruling order, the uprooting of accepted modes of social organization and the established rule of law, in order to foster a new mode of being, a new manner in which people might relate to each other. Revolt does not recoil from suffering and violence; it seeks to punish the oppressor in an act of righteous indignation. In revolt, one rejects the claims to power of the current regime and thus, far from encouraging the fellow feeling of sympathy, insists on a sharp distinction between the righteous self and the malicious and malign other.

One might impute a certain temporal division between pity and revolt. Pity looks toward the past and the consolations of the recognition of grievance. In this sense, pity can negate one’s hold on the present; pity can be debilitating (this is Nietzsche’s critique of pity). Indeed, the negativity of pity is set in stark relief when one considers the fact that the phrase “What a pity” is interchangeable with “What a shame.” Although pity is not the same as shame, it is not far from it. While my pity for person X is not synonymous with my feeling ashamed for person X’s condition, there is a sense in which I am identifying with X’s humiliation. In this manner, pity may involve withdrawal from the world.

Revolt, on the other hand, is future-directed. In one way of thinking, we might say that revolt is the negation of the negativity of pity. Whereas pity sacrifices the present in favor of the past and its consolations, revolt sacrifices the present (which is held in opprobrium as unjust) to the blandishments of the unforeseen future, a future unmoored from any connection with the past and present. This is why revolutionaries are often dubbed “radicals” (from the Latin radix, meaning “root”): they seek to uproot tradition, to start anew. Revolutionaries aim for a utopia, a term that literally means a “no place”, insofar as it has no connection to the reality as currently lived.

We see Julio at the crossroads of pity and revolt (Misericordia and Ongpin) in several shots across the running time of the film. Brocka ensures that the street signs are blatantly apparent; at one point, Julio is actually leaning against the post, with the signs looming over his head as he stares disconsolately toward the building that he believes imprisons his lost love. Pity and revolt are seen as the two possible paths that Julio might follow in his attempt to reconnect with Ligaya. In portraying Julio embedded in Manila’s geography, the film provides a cartography of the decision he must make. But the symbolic import of these signs reaches farther into the depths of the film’s meaning.

Ligaya left their province with a Mrs. Cruz (Juling Bagabaldo), who convinced Ligaya’s mother to allow the young lady to move to Manila where she would be educated. The family only received one letter from Ligaya after her arrival and then a letter from Mrs. Cruz claiming that Ligaya had absconded with some of Ms. Cruz’s jewelry. Julio, sensing that Ligaya was in danger, went to Manila in search of her. For months he attempts to find and track the elusive Ms. Cruz, accosting her in public only to be derailed in his pursuit when she calls to the police, claiming that he’s mugging her. Despite these impediments, Julio manages to follow her to this corner of Chinatown where he discovers a Chinese merchant named Ah-Tek (Tommy Yap) who denies ever having heard of Ligaya, but who we eventually learn has married her.

Meanwhile, Julio has no choice but to provide for himself. He gets a construction job at a building site where he does excruciating labor for two-and-a-half pesos per diem while on the books he earns four (the unscrupulous foreman pockets the remainder). Workers operate in unsafe conditions, overtime pay is no different from regular pay, and workers are summarily dismissed without warning as the building nears completion. The company employs a cruel scam that forces the workers to “buy their own wages” wherein they claim a lack of funds at pay time but will front the worker the money for a ten percent commission (no one seems to comment on the paradox that the company has no money to pay the wages but has money to loan out)—this is bald theft in the name of capitalism and gross inequity. At the same time, pimps and prostitutes are allowed onto the site (where many of the men take up residence at night, unable to afford proper lodgings) and connive the workers out of what little money they have remaining.

Many of the workers dream of moving on to higher things. Benny, one of the most affecting of Julio’s colleagues, longs to be a famous singer and practices while working, to the disdain and bemusement of his fellow workers. He dies in a careless accident at work. Atong (Lou Salvador Jr.) shows great kindness to Julio, instructing him on the modes of behavior at the work site and taking him home for a meal with his father and sister. Atong is wrongly accused of a crime and dies in prison. Imo (Pio de Castro) takes night courses. He does escape the cycle of poverty and lands a job in business. Dressed in a suit and condescending toward the waitstaff, Imo later treats Julio to a lunch. We are clearly not meant to admire Imo’s ascent. He simply moves from the level of the oppressed to a position of complicity with the oppressor.

The whole film seethes with rage against colonial oppression without ever becoming overt agitprop. Rather, its narrative interweaves the personal and the political, demonstrating that the rupture in Julio’s idyllic (if impoverished) provincial life through the loss of Ligaya was not simply an isolated unfortunate incident but a symptom of a diseased body politic. The very name of the beloved reveals the allegorical relationship between the love story and the critique of the social system. Ligaya Paraiso means “joy[ful] paradise”. By removing her from the province, represented in the film as more “authentically” Filipino, Manila in the Claws of Lightmakes Julio’s journey into an attempt to recapture a lost past. This is the element of pity and regret in the film. Someone he valued has been desecrated, her innocent beauty enslaved to the depravities of lust satiated through financial transactions. In this debauched context, the name (“joyful paradise”) takes on the cynical ring of an advertising slogan. Authentic reverence for the inviolable distance one maintains with respect to revered beauty is replaced by the ever-encroaching, ruinous and leering embrace of capitalism’s willingness to defile beauty in the name of profit.

Capitalism is like the fellow that has a hammer and so everything in the world appear to him to be a nail. Capitalism necessarily views everything as fungible, that is, mutually interchangeable; this is the cost of a logic of exchange. No matter what you have, capitalist logic insists that it can find something you would take for it. There can be no qualitative hierarchy of values under a capitalist system, only a quantitative one. One thing isn’t worth more than another because of some intrinsic quality of the thing, it simply costs more. This is what money expresses. Dollar bills are inherently worth exceedingly little. The idea that a certain number of these bills is “worth” a couch and another number of bills is worth a house ought to inspire incredulity. And yet we recognize that it is not the dollar bill as such that is worth anything, but rather what it represents. It represents the flow of exchange and the stockpiling of exchange value.

Now, we like to maintain the fiction that there are things that money can’t buy—the most typical assertion being that money can’t buy love. But capitalism reduces all values to their surface (largely visible) phenomena. It’s true that Ah-Tek (who simply buys Ligaya from Mrs. Cruz) can’t buy Ligaya’s love. When Julio finally runs into Ligaya in Manila, it becomes immediately clear that her affection has not strayed. But she is now married to Ah-Tek, lives with him, attends to his needs, and has born his child. These are the surface attributes of love and they were all purchased by Ah-Tek, who then had the temerity (I’m sure he would consider it the right) to insist that Ligaya thank him for saving her from the torments of morphine addiction and the need to sell her body to a wider array of clientele. Hence, Ligaya is reduced to the status of commodity and is meant to be grateful that she is a highly valued commodity. Ah-Tek threatens her with death or debasement (by returning her to Mrs. Cruz for resale) should she not abide by the conditions of her purchase. The conditions of her life under capitalism is equivalent to the conditions of purchase. Whatever joy she might find in her child and the relative ease of her life has to be “bought back” by her acquiescence to the odious demands of her hated purchaser—just another scam perpetrated by those in control of capital.

Manila, however, insists that capitalism is not the “natural development” of a modernizing nation, at least not in the context of its representation of the Philippines; rather capitalism and its depredations are imposed from without by an extended colonial rule—first at the hands of the Spanish and then the Americans. Nevertheless, the characters hesitate to do something about it. Pol (Tommy Abuel), one of Julio’s most reliable friends, complains about Filipinos at the local restaurant who insist on speaking only English and yet discourages Julio from joining a band of communist protesters against the current regime. The construction workers lament the usurious schemes of those in charge but they shrug off their disadvantage as just the “way it is”. Notice the tenor of that phrase “this is the way it is”: in the mouth of the oppressor a threat and in the mouth of the oppressed a sigh of resignation. In neither case does it look forward to the future but merely asserts an inequitable present or acquiesces to it.

“Isn’t it a shame,” we might say in response. Or we might decide to revolt. We might decide to take action. Julio, in the end, attempts just that. But we have seen him temporizing at the crossroads of pity and revolt for so long that it ought not to surprise us that he has trouble committing to action without misstep. His act is too violent and too personal to overthrow an entrenched system of disenfranchisement and injustice. When he commits it, he is accosted, not by the “powers that be”, not by those who have a financial stake in the perpetuation of the capitalist inequity portrayed in the film, but rather by other members of the oppressed classes. He is attacked by others like himself.

This, we are to understand, is capitalism’s major feat: to not only control the masses contractually but to make them complicit in their subjugation. All that resentment that the oppressed rightly feel and that ought to be channeled into a revolution, an uprooting of unjust conditions, instead gets turned on to other victims. Transgression of the law warrants severe punishment. Such an axiom seems self-evident. But laws are in place to maintain the status quo. They have an outsized stabilizing effect; laws inspire pity and shame. Shame serves to curb non-normative behavior, behavior that might incite change. Pity offers the weak consolation of fellow feeling in suffering: “Isn’t it a pity, isn’t it a shame.” Meanwhile, everything remains the same because that is “just the way it is” and the “way it is” has a tendency to perpetuate itself.

True change requires a leap of faith, a leap into the unknown, the unforeseen, the unpredictable. With change comes the real possibility of utter failure but for the oppressed the unwillingness to change comes with the guarantee of the failure of the majority in order to fund the outlandish success of the few. But the trick of capitalism is to relieve that pressure valve by making the oppressed complicit in their oppression. In some cases, like with Imo, that means they must achieve a modicum of success; in other cases, it’s enough to simply want all members of the class to suffer under the same burden. The pleasure taken in resentment (resentment, oddly, not of the oppressor so much as of anyone attempting to break free of their chains) helps fuel the engine of capitalism.

There can be no true revolution that leaves the current set of laws intact. Revolution is meant to be overwhelming, it’s an irruptive force that seeks to explode the status quo. This is why revolutions are relatively rare and why they so often revert to another level of oppression. Just like no battle plan withstands the first contact with the enemy, no revolution withstands its continued contact with reality. Because the revolt involves inherently the leap into the unforeseen, it cannot be rigorously controlled. And there is no going back to the past, no matter how alluring that “joyful paradise” might be. All counter-revolutions fail to re-instantiate the conditions of the past. We might lament inaction but the reason for that is evident: action is unpredictable and arduous. Perhaps this is why Julio and we ourselves linger so long at the crossroads of pity revolt. Isn’t it a shame?

Criterion Collection recently released a blu-ray edition of Lino Brocka’s masterpiece Manila in the Claws of Light. A sad but beguiling film, Manila offers many more scenes that might inspire philosophical and political reflection than the few I was able to discuss here. It bears repeated viewing, discussion, and argument. Criterion Collection’s restoration is gorgeous and the company has provided a few extras to accompany the film itself, including an underwhelming introduction to the film by Martin Scorsese, a 1987 documentary about Brocka, a 1975 documentary on the making of the film (the discussion of the filming of the death of Benny is interesting), and an interview with filmmaker and critic Tony Rayns.