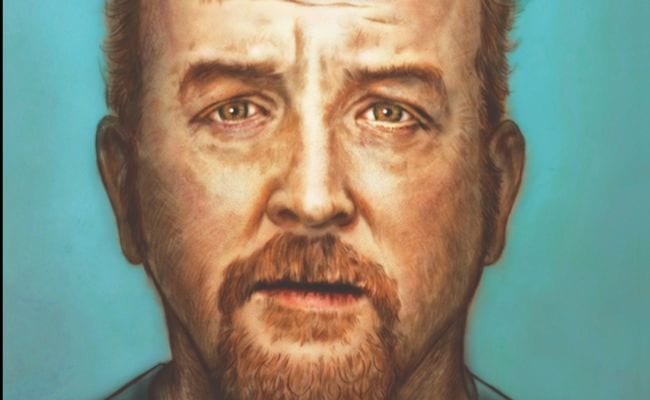

For readers who aren’t already fans of the comedian, Louis C.K. and Philosophy: You Don’t Get to Be Bored is probably not a book that they are likely to pick up, but those people would be missing something surprisingly illuminating and genuinely entertaining.

Both off-screen and often as the version of himself that he plays on FX’s Louie, Louis C.K. gives the sense of an intelligent and charming man, and comes off more than anything else (contrary to many at his level of fame) as unassuming. As the editor and contributors to this book demonstrate, it’s in this unassuming quality Louis possesses that something profound stirs. Louis C.K. and Philosophy works to pull that something out and study it.

Is Louis C.K. a philosopher? Of course not, both he and the writers of this book stress from the beginning. But that’s part of what makes his comedy so fascinating and important, we’re told. He isn’t a philosopher, and yet both by circumstance and purposeful design his comedy percolates with observations on, and even possibly some answers to, life’s most important questions. Philosophy can’t be artificially contained to those who claim to articulate it, the authors would surely argue. It also exists in those who practice it and it’s clear that Louis C.K. practices something deeper than mere “comedy”.

Louis delivers this line in Season One of his television show: “My life is evil. There are people who are starving in the world and I drive an Infiniti. That’s really evil. There are people who just starve to death; that’s all they ever did … that’s all they ever get to do.”

It’s unlikely that anyone goes to a comedy club to be reminded of the cost of their relative affluence or of the moral implications of their drive there, but again and again, even as his comedy makes us think more deeply about our lives and the consequences of our choices, Louis helps us find humor and satisfaction in a world that coldly disregards us or our suffering (Schopenhauer). He admonishes both his children and the rest of us for not appreciating the full spectrum of life: from its overlooked wonders (Socrates) to its often absurd emptiness (Heidegger).

Is such philosophy the exclusive domain of Western thinkers? Are there so few experts on Eastern philosophy to contribute to a work like this? It can’t be said that no Eastern philosopher’s work intersects with Louis C.K.’s material. In fact, two whole chapters are devoted to the acceptance of suffering, a central subject to Buddhist philosophy. Yet the contributions of Eastern philosophies to the collection don’t go beyond a single, brief brush with Buddhist teachings.

Is there not as much insight to be gleaned from Sankhya philosophy as there is from the Stoics, the Epicureans, or the Existentialists? One essay does expound on the connections between the Buddha’s philosophy and Louis’s comedy, but the connections made are brief and it’s hard to imagine with as many chapters devoted to the emptiness, suffering, and despair of life here, that there wasn’t more to say about Louis’s intersection with Buddhist or Indian philosophy. What seems far more likely is that the absence reflects a narrowness in the philosophical catalogue of American academia.

Even the Western philosophers drawn upon are the usual suspects — Nietzsche, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, Sartre. Of course, it’s possible the writers and editor wanted to draw upon the philosophers most readers are likely to recognize. But for a series presumably devoted to instructing the everyman in the philosophy of everyday life, isn’t there room to expand the stable? After all, where is Confucius? Inarguably, one of the most influential philosophers in history, Confucius’s philosophy even spawned Neo-Confucianism just as Plato’s eventually spawned Neoplatonism, discussed in the book.

In fact, compare this excerpt from Confucius’s Analects, Part 16:

There is the love of being benevolent without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to a foolish simplicity. There is the love of knowing without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to dissipation of mind. There is the love of being sincere without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to an injurious disregard of consequences. There is the love of straightforwardness without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to rudeness. There is the love of boldness without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to insubordination. There is the love of firmness without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads to extravagant conduct.

With this quote from Louis in Chapter 8, “Should Jane Get to Be Bored? “:

I do love to learn. It’s all I feel like I’m ever doing. It’s really the best you can do in life, is learn.

In setting up the discussion of Louis’s love of learning, the contributor quotes Aristotle as saying, “Every human being, by nature, desires to know.”

It seems farfetched to suggest that there wasn’t room for discussion of Confucius’s philosophy in the pages of the book, at least alongside the chosen philosophers.

And yet, despite the remediable lack of range, it’s undeniable that all of those philosophers drawn upon — from Epictetus to Sartre — still have as much to say to us today as they ever did. The contributors and editors of this book have done an otherwise excellent job of leading us along the way.

There is some repetition, both of quotes from Louis’s comedy and of the points made off those quotes, even while the contributors find new philosophers to bring into the discussion. Otherwise it’s an insightful book that manages to preserve the entertaining voice of its subject while giving light, brief glimpses into some of life’s most enduring questions.

One of the best chapters comes last, “An Hour”, which begins by discussing Louis’s process of developing and delivering an hour’s worth of material each year before scrapping it and starting anew. Although not a practice unique to Louis, the author explains how the practice embodies the lessons the rest of the book has shown us to be true of Louis’s comedy and its development. For Louis, the impetus away from continuing to deliver the same stale, less-insightful material of his early years came in the form of his children.

Both as an insight into Louis’s development, and as a lesson to be learned from Louis’s comedy itself, the contributor writes: “Sometimes you need an external force to compel you to get down to the business of introspection.” Whether it’s the birth of his daughters or ejaculating into a $2,000 trumpet at a cheap peep show, Louis’s personal life has given him numerous of these external forces and, as his audience, we’re better off for it.