The 1980s weren’t particularly kind to the singer/songwriters who’d emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The recording studio became the producer’s fiefdom and the acoustic music that had characterized the work of people like Joni Mitchell and Carole King became passé. Artists affected by these changes either attempted to move with the times or, like Laura Nyro, recorded far less frequently. Acoustic or semi-acoustic pop music was still around, but performers such as Suzanne Vega and Tracy Chapman had to enter the marketplace under the folk banner to get away with it. Others, including Mary Chapin Carpenter, managed to be singer/songwriters by concealing their work beneath a veneer of ‘country’. But in pop at least, acoustic was scarcely welcome. There wouldn’t be any sort of turning-of-the-tide until the appearance of people like Tori Amos and Sarah McLachlan at the end of the decade (and, remember, Amos had to fight to make an album of piano-accompanied songs, having first been put through the electric mangle with her real debut, 1988’s Y Kant Tori Read).

Few singer/songwriters experienced the upheaval of the 1980s quite like Melissa Manchester. While each of the prominent 1970s singer/songwriters issued a keeping-up-with-the-times album – Carly Simon (Spoiled Girl, Epic, 1985), Carole King (Speeding Time, Atlantic, 1983), Joni Mitchell (Dog Eat Dog, Geffen, 1985), Janis Ian (Uncle Wonderful, Interfusion, 1986) – Manchester went one (or rather, three) further, issuing a trio of synth- and programming-orientated works – Hey Ricky (Arista, 1982), Emergency (Arista, 1983) and Mathematics (MCA, 1985). These were albums that reached out to a new audience at the risk of alienating the old one and not everyone was prepared to go on the digital journey with her.

Decades later, however, the dust has settled. It’s possible to listen to the music with unjaundiced ears and hear its ebullience and charm. And now that Mathematics, perhaps the most vociferously 1980s of all Manchester’s albums, has been remastered, expanded to twice its original length and reframed as Mathematics –The MCA Years, it no longer seems like any sort of aberration, but rather a bracing, dynamic set, with a pushy, mischievous spirit. The expanded Mathematics has been handled by the inestimable Second Disc label, an imprint of Real Gone Records, a reissues powerhouse whose work is high-quality, conscientious, respectful and stylish. It comes with a scrupulously well-researched essay/interview by Joe Marchese, and lots of extras, including three album outtakes and some of Manchester’s film theme-songs (singing on prominent soundtracks turned out to be a fruitful side-career for her in the 1980s).

“Everything is about context,” says Manchester, “and the sound was changing because of the times. Disco was in full swing, electronic music made itself very present, and Clive Davis and all the guys at Arista and subsequent companies wanted to see how I would fare with a more current sound”. As we connect on the telephone, Manchester is as warm and personable as her music suggests, always quick to laughter and never less than accommodating when asked to discuss her work. She sees her musical life as being divided into ‘artistic chapters’, and the electronic chapter can, perhaps, be seen as the third.

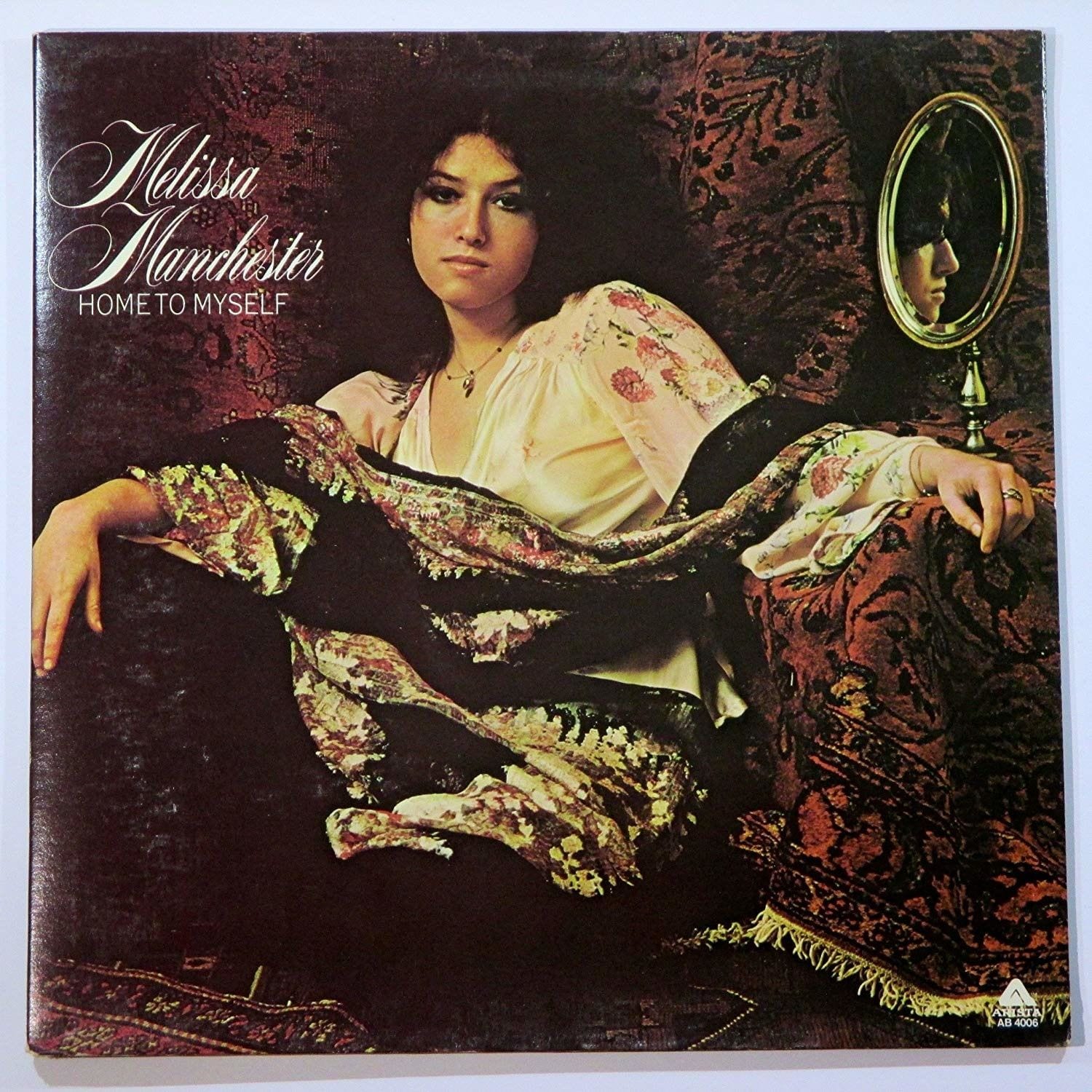

Chapter One had begun with Home to Myself (Bell, 1973), a charismatic, under-appreciated album that introduced her to the public as a singer/songwriter in what we would now see as the classic mold. Like its even better followup, Bright Eyes (Bell, 1974), the thrilling, unusual title track of which remains one of her crowning achievements, it deserved to mentioned in the same breath as Carly Simon’s No Secrets and Carole King’s Tapestry. While Manchester shared a number of qualities with her peers (an intimate, conversational songwriting style; accompanying herself on the piano; a Bohemian sartorial presentation), she had at least two characteristics that helped her stand out – a rich, enveloping, dramatic voice and an affinity for R&B and soul, particularly evident in the up-tempo songs from her third album onwards, making her a forerunner of Teena Marie.

That first chapter reached its zenith with the gold-selling Melissa (Arista, 1975) and the hits “Midnight Blue” and “Just Too Many People” and came to an end with the 1978 release, Don’t Cry Out Loud. At that juncture, Manchester’s singles and albums hadn’t been performing to Arista’s expectations. She fashioned an album with genius-producer, Leon Ware (notable for, among other things, Marvin Gaye’s I Want You) that was to have been called Caravan. Her label, however, had other ideas and at the last minute, she was urged to record “Don’t Cry Out Loud” (Peter Allen/Carole Bayer Sager), produced by Harry Maslin with an enjoyable but histrionic orchestral arrangement. The parent album was changed from Caravan to Don’t Cry Out Loud. The title track was a hit, but it had the effect of almost burying one of the best albums she had ever made; none of the sparkling, Leon Ware-produced tracks was given its chance to shine and Manchester’s achievements, remarkable songs like “Through the Eyes of Grace” (not to be confused with “Through the Eyes of Love”), went by without comment.

The success of “Don’t Cry Out Loud” spawned Chapter Two of Manchester’s recording life; for her next few albums, she would be presented with big-production numbers by outside writers in the hope of securing another “Don’t Cry Out Loud”-sized smash. She would write the balance of the albums herself – a kind of 50/50 split. This chapter would involve another shift; she began to sing in a more formal, musical theatre-indebted style. Compare, for example, her performance of “The Warmth of the Sun” (from 1977 covers collection, Singin’) with “If This Is Love” (from 1981’s For the Working Girl). On the former, the vocal is clearly in a pop/rock/soul vein, while on the latter, Manchester’s diction and song-styling have become more ceremonious, posh and stately, as if she’s in formal evening-wear and a tiara rather than rock ‘n’ roll or modish apparel. I make this observation not to suggest that one approach is better than the other, but merely because it’s a defining characteristic of the ‘second chapter’.

The formula was used for Melissa Manchester (Arista, 1979) and For the Working Girl (Arista, 1980), and it kept her in the charts but, yet again, at a cost; her best work was hidden on album cuts. “Lights of Dawn”, a devastatingly effective piano ballad and a continuation of what Manchester had been doing with “Through the Eyes of Grace”, was allowed to slip by, while pleasant but comparatively commonplace material like “Fire in the Morning” was promoted.

One exception was the single release of “Lovers After All”, a superb, quiet storm soul ballad written by Manchester with Leon Ware and sung as a duet with Peabo Bryson, which reached the R&B Top 40 in 1981. Manchester’s next big success would herald the start of Chapter Three – the synth years. It was, of course, the irresistible, frothy pop confection, “You Should Hear How She Talks About You”, written by Tom Snow and Dean Pitchford, lead single of her tenth album, Hey Ricky (Arista, 1982). It secured her a #5 placing on the Billboard 100 and a Grammy.

Emergency (Arista, 1983) came next. Like its predecessor, it was produced by Arif Mardin. Where Hey Ricky merely dabbled with the new synth sounds, Emergency bought into them wholesale. It attempted to bag Manchester another hit in the vein of “You Should Hear…” with Tom Snow’s “I Don’t Care What the People Say”, but it wasn’t to be. Manchester’s relationship with Arista was, by this point, fractious and beyond repair, and she set off for pastures new, settling at MCA for Mathematics. “I was in a state of high frustration,” she recalls. “I had been with Arista for a long time. In retrospect, of course, I’m very grateful that Mr Davis and his company believed in me long enough to hold on to me for so long. But at the time I was on such contentious terms with them and just happy to be somewhere else, happy to be with a company that believed in my talent and my potential and wanted to give it a go.”

The deal with MCA gave Manchester the chance to work with a new team, but the platform it would afford her would not actually be dissimilar to the one she had just fled; her album would be assembled by committees of producers, programming/sequencing wizards and external songwriters (Manchester contributed to four of the tracks as a co-songwriter), and she would sing to tracks that had already been recorded by the time her vocals were required.

It was a world completely different to the one she had entered at the time of Home to Myself, when she’d been given creative freedom and her notable gifts as a pianist were an integral part of the recording process. But the important thing for Manchester was to find a way to keep creating and stay active. “I don’t know that I had great courage to stand my artistic ground and say, ‘Oh no. I won’t be part of the electronic scene. I’m going to be a purist all my life’. I was curious enough to walk down a new path and try a new adventure and see if I could be part of it comfortably and find an artistic way to justify using my voice, which was quite powerful, in a really different setting to the one I had been used to. It was interesting. I had to let go of a lot and surrender a lot. For me, the comfortable place was always the song – is the song interesting enough, are there musical changes that are interesting enough, are there lyrical components that are interesting enough? Because if you’re successful with songs, you have to sing them for a very long time.”

One big difference in this new era was that Manchester was now recording the kind of music she quite pointedly did not listen to at home for pleasure. “No! Not at all,” she laughs. “Classical music calms me down when I need to think about something. Jazz calms me down when I need to think about something. R&B calms me down when I need to think about something. Electronic music is never my go-to!” This revelation makes her bravery in being willing to enter the electronic milieu apparent in a way it might not have been at the time. Back then, it might have seemed merely a shrewd commercial decision, but Manchester was, in fact, just trying to identify routes to enable her to keep going, stay on radio, and remain in the collective consciousness of an audience.

“And what’s really interesting about my foray into the world of electronics,” she continues, “is that some of my students really love this album [Manchester teaches different aspects of songwriting at USC and other places of learning]. They really love the energy of it. When it was being re-released, I thought, ‘Well, perhaps I should listen to some of it’ because I hadn’t listened to it in a long time”. Manchester duly sat down and was struck by the effervescence of Mathematics. “It was very cheeky, fun and buoyant.”

Listening today to the ten tracks that make up the original album, you hear what sounds like a commanding, confident singer at the peak of her vocal talents but she found the recording process unsettling. “I was in a studio where I was asked to sing on tracks that didn’t sound or feel like the past sound and feel. I couldn’t tell if it was good or not because it was so aggressive and so muscular – a different muscularity to acoustic instruments. I so loved and respected the musicians I was working with, and I enjoyed the songs. Some I had a great affinity for and some it was fun to write, but it was the production end where I said, ‘OK, I’m going to trust this. I’m going to trust what I’m listening to and I’m going to trust these people because I don’t really get it, and they know I don’t get it and I can’t stay in the studio too long, listening to this. But apparently a lot of people really like this sound, so I’m gonna trust and I’m going to surrender’. And that’s what I did.”

For the songs with which Manchester had involvement as a writer (“Mathematics”, “The Dream”, “Restless Love”, “Just One Lifetime”), the process involved yet more surrender. Instead of participating in their arrangements and instrumentation, Manchester would play her part in their writing, sometimes still starting in the traditional way at the piano, but then pass them over to be clothed and accessorized by George Duke, Brock Walsh, and Robbie Nevil, with Quincy Jones in an Executive Producer role.

“They had so many new toys to play with musically. I would give them the songs and then they would effectively recreate the world of the song. They would blow up the inner life of the song. It would become an explosion of sounds that I simply didn’t have in my imagination. And because I was not adept in that world, I was just handing over the songs. I would never know what I was coming in to hear in the studio. It was really thrilling in that way, because it literally was a whole new world. It was the producer’s arena. It was really wild to hear my great, big voice in a world I barely recognised.”

Photo: Brian Aris / Courtesy of Real Gone

In hindsight, Manchester thinks that Mathematics might have turned out differently had her soul/groove leanings been picked up on and utilised. It’s certainly the side of her that earlier producers, Leon Ware and Vini Poncia, were attuned to. “It was a frustrating battle. Songs like “Victims of the Modern Heart” have a strict, up/down pop sensibility whereas I was always living in the grooves of Earth, Wind & Fire – I just couldn’t get anybody to listen, to swing from side to side as opposed to up and down.” It’s easy to imagine Manchester navigating the 1980s with a more R&B approach, something more in the Michael McDonald or Rufus vein, something akin to the two 1980s albums that her former collaborator Leon Ware made as a solo artist on Elektra. There had been an attempt to pull in that direction on “Looking for the Perfect Aah” and “Your Place Or Mine” (both co-written by Manchester) from Hey Ricky, but it wasn’t developed any further. For MCA, pop, not soul, was the order of the day and Manchester was more than up to the task. Despite not getting the grooves she was after, she was not unappreciative of what she did get. “When I listen to a song like “Energy”, she says, “it’s a really masterful production. It’s a really great, completed idea.”

The roller disco vogue, although post its zenith, was still of sufficient cultural import that the production of “The Dream” (written by Manchester with Brock Walsh and Bill Livsey) was built around it, with Duke operating no less than four machines; the Synclavier 11, the Memory Moog, the Yamaha PF15 and the Prophet V. “It has that pump to it because it follows the body movements of how you skate,” says Manchester. “It’s an optimistic anthem, and that’s where my heart lies. When I listen to it, it’s very evocative of those times. When I listen, I smile to myself and think, ‘Yeah – you wrote that song’.”

“Shocked” and “All Tied Up”, which originally brought Side One to a close, are also suggestive of exercise, constructed with tight, aerobics-ready rhythms and tart lyrics full of snappy couplets. While “Shocked” is an entertaining, noir-ish melodrama, “All Tied Up” reveals the limitations of male writing committees. Like “You Should Hear How She Talks About You”, it is an example of authors attempting a female narrative voice and settling for ‘I’ve been hurt, but I’ll show you!’ or ‘he loves me, he loves me not’ teenage soap opera. As a result, in an interesting paradoxical quirk, the narrative concerns of the work Manchester made as she entered her 30s are far more adolescent, boy-crazy and coquettish than those of the material she sang in her 20s when she was doing all or most of the writing herself.

Just as Manchester was now making the kind of music she wasn’t always inclined to listen to, by the same token, the clubland aspects of Mathematics were designed to go down well in environments she didn’t make a habit of visiting. “I was not a club crawler. I just never had the energy to do that. I would hear about it and I didn’t live far from the clubs. I knew it was a major scene, but I was on the road so much that I was mostly exhausted. I would hang out with friends and we would cook and talk and drink wine. The idea of going out to clubs in addition to writing, performing and touring never had much appeal to me.”

If, on Mathematics, there’s a link back to the earlier artistic chapters of Manchester’s recording career, it’s to be found in the closing ballad, “Just One Lifetime”, written by Manchester with Tom Snow (Snow is a hugely successful songwriter who also had a few shots at album-making in the 1970s and 1980s). Although it’s more knowingly commercial than the ballads Manchester wrote at the outset of her career, with a more universal, less conversational narrative, it was the closest Mathematics came to throwing a bone to her original fan-base. With its swelling orchestral arrangement and big, belter’s chorus, it was a reprieve from the out-and-out electronica of the rest of the album.

“I said, ‘really, fellas – you gotta give me one ballad, otherwise I really won’t know who I am here’. I think part of my struggle was to find a place for me. A place for my soul in this new world where my soul was being shaken. I was in a land I didn’t really understand. I was a willing traveller, but there was so much I didn’t understand. When I presented the song, it was accepted because it was a lovely song.” Not only a lovely song, but – in something of a vindication of Manchester’s gifts – of all the songs on Mathematics, it was the most enduring. Years later, when Barbra Streisand was preparing her 1999 album, A Love Like Ours (something of a concept album, inspired by finding love with James Brolin), Manchester submitted it for consideration.

“It got back to me through her executive producer, Jay Landers, that she liked the choruses very much but she couldn’t quite follow the verses. I called Tom Snow, who had had songs recorded by Streisand before, and I said, ‘Would you consider deconstructing and then reconstructing the verse and maybe the bridge with me?’ and he said, ‘sure’. And what was interesting was that it was like writing for theatre. We studied where she was in her life, how she was on a spiritual path, and it seemed to have opened her heart to find this love. That was what we reflected in the song, and honestly, I think it made a better song. I re-demoed it, and it was thrilling when she said ‘yes’ and not only recorded it but sang it at her wedding.”

It would be an oversight not to make one more observation about Manchester’s synthpop years. Hand-in-hand with the musical makeover came a physical one. By 1985, Madonna was in the ascendant. From that point on, the degree of emphasis placed upon a performer’s sex appeal would be greater than ever before. It was also sex appeal of a particularly prescriptive nature. This was not the kind of having-fun-with-the-camera, playful sex appeal of Carly Simon in the mid-1970s. It was somewhat colder; all diets and athleticism.

In the run-up to Manchester’s 1982 album, Hey Ricky, image-making personnel were enlisted and along with the album came a grand unveiling of her new look – dangerous cheekbones, sleek, wet-look, gamine haircut, couture outfits, and gym-ready physique. As with the music, Manchester did her best to have fun with the experience. “I was willing to try it as part of the journey. It was fascinating. Suddenly, I was wearing clothes that I could not imagine ever wearing before. The leather jumpsuit [featured on the cover of 1983’s Emergency] was Exhibit A. And being photographed by Helmut Newton for heaven’s sake!”

British shutterbug, Brian Aris, took the striking portraits for Mathematics. While the cover goes for a black-and-white, classic feel, Manchester’s hair slicked down, a few liberated kiss-curls abseiling down her forehead, wrists adorned with jewelry, the back is thoroughly cutting-edge, 1985 through and through. Looking wonderfully serious, Manchester is depicted with washes of colour on her forehead and shoulders. A chunky, geometric earring dangles perilously from one earlobe. Mathematical equations are written in makeup on her temples and clavicles, and it’s all topped off with a gravity-defying hairdo. “That was a major hoot – with all that stenciling on my face and my hair piled up in a mohawk. It was like the costume parties of the twenties where people went nuts and morphed into other characters. It was serious fun.”

In the end, Mathematics didn’t perform as well as it deserved to sales-wise. Manchester gave it her all, making her first promotional video for the single release of “Energy”, choreographed by Toni Basil, who’d overseen David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs tour (and would go on to work with him on the Glass Spider tour of 1987). She also toured the album. “It was fun to be moving around a stage that was on a major set with ramps. It was a new and thrilling. I had background singers that were costumed up and musicians playing to click tracks for the first time. It was really like sticking your toe in the deep end of the pool. Some fans said, ‘What happened to you? Where are you? What happened to the singer/songwriter that we new and felt close to, who had value in our lives in the 1970s?’. But part of the trick of a career is trying things. If you have a long enough career, you can look in retrospect and think, ‘Wow – look at all the different things you did. Look at all the things you tried. Some worked, some didn’t, some were deeply interesting, but all were creative.”

In the aftermath of her time with MCA, Manchester had two children and worked in a variety of fields, including musical theatre, television, and cinema. She moved to Mika/Polydor for 1989’s Tribute, an album of standards on which she paid homage to her favorite female vocalists. It was perhaps the best her voice had ever been captured on record. Then it was on to Atlantic for 1995’s If My Heart Had Wings, on which she began to steer back to adult-orientated popular music, even if it featured little to none of her own writing (that side of her creativity was expressed through composing the score for the 1995 musical, I Sent a Letter to My Love ).

Manchester looks back on her dalliance with electronica fondly. “You know, what I learned about myself, which is one of the most important things that I’ve learned about myself, is that if I’m in the midst of a creative endeavour and I feel weird about what’s going down or I don’t understand what’s going down or if what’s going down isn’t making sense to me, is to slow my brain down. What that allows me to do is find my place in the room as opposed to being overwhelmed and leaving the room, not being part of the discussion, not being part of the decision. I’m there for all the decisions. I don’t just sort of stamp out of the room and say, ‘You do it! I can’t deal with it any more!'”

That is a strategy she thinks is important for all creatives: “Learn how to breathe and slow your brain down. You may have to leave the room for a few minutes and regroup, but you come back into the room much clearer. You understand what the pertinent questions are; you can reframe what the goal is, you can address what you don’t understand and ask somebody to explain to you why something is a good idea or what your creative input is. It took me a while to learn how to do that. In the 1980s, I didn’t yet know how to do it because things were still coming at me for the first time. Life was coming at me fast and furiously and thank God I never got into trouble with drugs or alcohol or any of that stuff, because the work was so intoxicating in itself and so thrilling and exhausting, that I never wanted to miss any of it by being in an altered state.”

When pressed as to how she might have navigated the choppy waters of the late Arista and MCA years differently, it is the surrendering of aspects of her artistry and decision-making that she would be inclined to reconsider. “What decisions would I have made differently, what would I have not surrendered, what would I have insisted that somebody explain to me…? In those days women were not in production, hardly at all, if at all. You were still the girl singer in a roomful of men and although people respected my talent, I didn’t yet understand what respecting me meant. Those are life lessons. You can’t learn those lessons a second before you are ready and able to learn them, so that does affect your decisions. Choices have consequences, that’s how I’ve raised my kids, and that’s what I know to be true for everybody in the world. While it was a bit of a struggle to find my way with Mathematics and all that stuff, even Emergency and Hey Ricky, I did have the honour of working with Arif Mardin and I wouldn’t have changed that for the world, because I saw how a true master works. He truly was a master of his craft, a master musician, a master arranger, a master producer, a master gentleman.

“But what I think about when I look back at those times is how passionate I was about the work and the experience of the work, yet how unformed my consciousness was because that’s how young I was. When you’re in your thirties or your forties, you don’t think of yourself as being ‘young’ like when you’re a teenager, but still. The blessing for me of ageing and being a veteran artist and being a working artist still, very much so, is that I know what I know and I realise now what I didn’t know. As I jokingly say, it’s amazing how much you can accomplish while you’re unconscious! That was me to a tee! I had enough intuitive sense to make the journey and surrender to those who knew more about the scene at the time. So I don’t really have regrets about it because I couldn’t have changed anything. I was in the state that I was in. What really kicks in later is your power of discernment, your ability to slow down, your ability to reframe. It’s fantastic. That is the hard-won getting of wisdom that I so appreciate.”

The rediscovery of an old document helped Manchester extinguish any lingering negativity over her relationship with Arista Records. Although she left the company at odds with Clive Davis, there was recently a healing rapprochement. “Decades later, I found a letter that Clive Davis had sent me in the midst of his frustration with me and the mutual frustration towards him. It was a letter saying, “I really believe in you, but just try to step out of being the singer/songwriter and try to step more into being the entertainer.” And in the moment, I was in my 20s, it was frustrating to read it, but when I came across it decades later, regardless of my immaturity at the time and my lack of consciousness in that moment, I was so touched by the depth of his belief in me. I reached out to him right away and sent him an email to say, ‘We had a lot of success together, we had a lot of failures together, but the overriding souvenir that I take from our time together is my gratitude for your belief in my talent’. It was very touching that he got right back to me and said, ‘I only remember the fun times’. With maturity, there come real inner soul-shifts, and it allows you to reconsider what your grudges were, what the false beliefs were, what the evidence in the end supports. When my gratitude kicked in, everything fell into place, and it was lovely to have that resolved.”

Manchester did chart a course back to making albums of her own songs, first with 2004’s When I Look Down That Road and then with the impressive You Gotta Love the Life (2015). She continues to grow and adapt as a writer. In particular, a song on the second of those albums, a lyrically clever but uncharacteristically sad song, “The Other One”, is heart-rending in its description of the pivotal moment when the veil of illusion in a long-term relationship is lifted once and for all. In its melody and its fearless probing of painful truths, the song is an achievement to match or even surpass any of her past artistic victories.

“That is an example of hearing your inner self, that wise self in you, finally getting to rock-bottom in a relationship, to utter the words that you’re not supposed to say. It’s a statement of self-care, self-preservation and self-awareness. When you’re first writing, it’s like an alternative voice, so you just write because it feels so good to get stuff out of you, whether it makes sense or not. Now I’ve learned how to create a world that is more cohesive, more nuanced, more thoughtful. I’ve learned how to create lyrics that are true monologues. I’ve learned how to look for clues in my own writing so that I know where the character wants to go. The songs are deeper. On the other hand, when Carole Sager and I wrote “Come in From the Rain”, I’m amazed by how much we knew at such a young age. But it’s interesting how the mind works when you’re working at your craft for fifty years. It’s more precise and more discerning in the use of language and harmonics and things I simply wasn’t tapped into in those early years.”

She’s currently re-recording some back-catalogue. “It’s so it can be licensed, actually, because if you don’t own your masters, you don’t make any money any more.” Her musical, Sweet Potato Queens, is opening in Jackson, Mississippi. “That’s exciting, because that’s where it takes place.” Before ending the call, we take one final look back at Manchester’s 1980s experience. She sums it up as follows: “I remember the internal struggles I was having to justify taking part in music as it was changing. And yet I so wanted to be part of that world because I love creating. It’s more than just love. It’s a very primal need, that urge to create. It’s where I feel most alive besides being around my children. It’s where I feel most engaged… it’s beautiful.”

Melissa Manchester’s Mathematics: The MCA Years is out now on Second Disc Records / Real Gone Records.