With a career spanning seven decades and over 170 films, Michel Piccoli is an eminently familiar presence in French cinema and beyond. Born in 1925, he began his acting career in the mid-’40s on stage and in film. In 1956 he played a priest in Death in the Garden, the first of many collaborations with the Spanish Surrealist director Luis Buñuel, and in 1963 he appeared as an important secondary character alongside Jean-Paul Belmondo as the lead in Jean-Pierre Melville’s transcendent gangster film, Le Doulos.

It was another film of that year, however, that signaled Piccoli’s rise to prominence: Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt. Piccoli plays Paul Javal, a playwright and former crime novelist who has found success as a screenwriter in Rome working at Cinecittà. An American film producer, Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance at his most sneering) hires Paul to rewrite a troubled screen adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey for the legendary German director Fritz Lang (gamely playing himself). Jeremy uninhibitedly flirts with Paul’s wife Camille (Brigitte Bardot) and manages to get her alone in his sports car as the crew moves to his villa. Camille, wanting nothing to do with the vulgar American, she resents Paul’s acquiescence in allowing her to travel with Jeremy; moreover, Paul arrives at the villa 30-minutes late.

The centerpiece of the film is an extended sequence in the middle of its running time featuring only Piccoli and Bardot as their characters wend their way through a protracted and often bewildering argument in their apartment. Godot orchestrates the scene through a series of tracking shots, sometimes following the characters individually as they move from room to room, sometimes abandoning one or the other (or both) in the midst of an action, veering from one face to the other as they deliver themselves of threats and provocations, enticements and entreaties, sighs of boredom and groans of despair. Only rarely are both characters in the same shot, Godard usually reserves such two-shots for either those moments of precarious calm and seeming reconciliation or the most eviscerating upheavals and acts of violence.

Godard’s script deliberately obscures the underlying motivations of the argument except in the broadest possible sense. Sure, Camille objects to Paul’s willingness to allow the odious Jeremy to slobber over her in what she perceives as a cowardly attempt to ingratiate himself to the wealthy producer, and Paul is both bewildered by Camille’s mercurial shifts in behavior and terrified in his suspicions that she is withdrawing her affection from him. But the fight is disproportionate to such causes, or perhaps the causes don’t seem warranted by the situation. Moreover, the course of the quarrel occupies some kind of non-linear time. One of them becomes peevish with the other only to appear to drop the resentment altogether and become flirtatious; and yet the fit of pique that seemed to blow over simply erupts again, without reason, without cause. The characters, toward the end of the scene, even narrate their feelings regarding their fight and their relationship in a set of alternating voice-overs—but the narration does nothing to illuminate the foundation of the disagreement or the underlying basis of the hurt and indeed devolves onto redundancy.

The arbitrary relationship of argument to time is reinforced and ironized by the film’s score, composed by George Delerue. Godard employs a single phrase from Delerue’s “Thème de Camille” as a recurring refrain throughout the sequence, but he uses it in a manner that runs counter to our typical understanding of underscoring in film. It is too loud in the mix to be ignored, sometimes threatening to occlude snippets of the dialogue. Its sonic presence thus appears to be in line with a tradition of cinematic “swelling music” cues that draw scenes to a close. But this scene refuses to end. The phrase doesn’t always appear at climaxes within the argument. It is as likely to emerge in the midst of a relative lull in the contretemps as it is to burst upon a moment of heightened tension. Perhaps most striking of all, the theme drives to a rather insipid cadence that perfunctorily announces closure where none is to be found. The music resonates with a sort of washed-out version of the turn-of-the-century post-Romantic yearning one’s imagination might attribute to an epigone of Mahler or Sibelius. When you first hear its pleasant wafting violin figures, it might strike you as hinting toward the transcendent, but that merely serves to make its utterly identical, utterly pointless repetition deliciously banal.

Indeed, the scene is a miracle of protraction. The camera meanders about the apartment listlessly in a manner that conveys the aimlessness that infuses romantic altercation; the music comes and goes without logical connection to the action; the argument ebbs and flows unpredictably, emotions shifting dramatically and without warning. It feels horribly familiar, as though we are experiencing the frustrating, bitter, illogical, and elusive kind of argument that seems to so naturally arise between lovers—the type of dispute that feels so overwhelming necessary while being so obviously arbitrary and pointless, that battle in which the stakes become impossibly high while the incitation to conflict remains so trivial. The camera, the music, and the actors all collaborate to bring us inside the conflict in all of its counterintuitive, nonsensical forward motion. We don’t merely bear witness, we move toward the interior of the experience (all too familiar, all too regrettable) of that relentless push to disaster while every fiber of our rational selves decry the ludicrous nature of it all, but we stand helpless as the rational voice plummets into the abyss of mutual incomprehension.

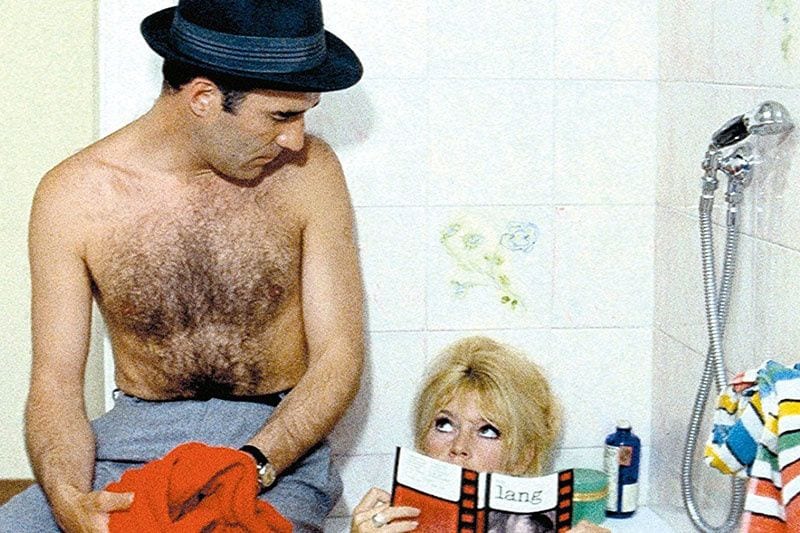

This miracle of protraction is also an actor’s tour-de-force and both Piccoli and Bardot mine the opportunity to plumb the depths of the alienation, disenchantment, and disaffection that always lurk around the edges of our romantic entanglements. The scene is full of actorly business. Camille sets the table and much later changes her mind, removes the plates, glasses, and silverware, and then (accidentally, it seems) lets them slip just as she arrives at the sink. She watches as the plates and wine glasses shatter on the floor, then gingerly steps over the glass to avoid cutting her bare feet. They each bathe—first Paul, then Camille—and move around the apartment in various stages of undress. They separately leaf through a book of ancient pornography. They walk, sit, lie down. The camera wheels about—movement is everywhere and yet the argument never truly progresses. They alternately caress each other and roughly push the other aside.

Throughout the extended scene, even as he bathes, Paul wears the fedora that he claims allows him to channel Dean Martin. It serves as something between a trademark and a talisman for Paul. On the one hand, he seems to see it as so ingrained in his personality that he is rarely seen without it (and never without it in this scene) and yet, by his own admission, the hat is emblematic of someone else: Dean Martin, an avatar of cool from a fast-disappearing age. On the other hand, as Camille increasingly threatens to leave him for reasons he seems unable to fathom and she seems unwilling to articulate, Paul clings to that hat as some small vestige of security.

One might think, by way of comparison, of another character played by another actor in another Godard film with a very similar hat: Jean-Paul Belmondo as Michel in Breathless (1960). For Michel, the hat is an accoutrement, an accessory that emblemizes his arrogant certitude that he is a man of substance. The hat is a sardonic nod toward his ability to put on a front and put one over on the suckers he meets everywhere he goes. The fedora for Michel is a plaything. It’s always around but he seems perfectly at ease when he’s not wearing it (for instance, in Patricia’s bedroom). The hat, for Michel, externalizes the cool, detached self-assurance he embodies for a world too stupid to understand without such a symbol. For Piccoli, as Paul, the hat is more than a mere symbol; it’s totemic. He uses the hat to gain access to a power he doesn’t possess on his own. Notice how small he looks in that hat while in the bath as Camille mocks him for its ubiquity.

Piccoli plays the part of Paul with a quietly strained reserve that constantly threatens to burst into acts of violence—sometimes simulated and playful, sometimes earnest and cruel. Early in the argument, as Paul begins to get frustrated with Camille’s recalcitrance toward him, he knocks his knuckles against a hollow metal statue of a woman in the living room. He raps upon the sculpture’s stomach and breast; amused, he points out to no one in particular that the sounds differ depending on the location. And yet one gets the sense that this is an act of sublimated violence, that he is reaching his limit with Camille. Any lingering doubts concerning this reading are dispelled in the very next moment. Camille returns to the room, brimming with renewed petulance; Paul snaps and strikes her hard across the cheek. It’s a truly shocking moment. As much as one might anticipate it owing to his knocking on the statue, the sudden rupture of violence throws the viewer off guard. Indeed, Piccoli gives nothing away in this moment. He goes from bemusement before the statue to a slight pained bitterness upon Camille’s return to this unforeseen eruption of unbridled anger. But as quickly as it arises, it’s gone; the argument continues unabated.

Critics often tout Piccoli’s self-assuredness. For many, he is an embodiment of cool in his own right. This seems a bit wrong to me. In many of the roles he plays, Piccoli works simultaneously at two levels of the character. The outer sensibility exudes a kind of savoir-faire and self-possession. In most situations, Piccoli’s characters appear to know how the world operates and they move fluidly within it. But the inner sensibility of these characters is another matter altogether. Paul wants to maintain self-control but because so much of his identity is wrapped up in having his wife’s affection, her disillusionment with their marriage threatens him with utter collapse. He attempts to vouchsafe his integrity of self by playing the role of the voice of reason within the argument, implying (sometimes stating) that Camille is behaving erratically. But the appeal to logic inevitably crumbles to reveal a bitter desperation in Paul’s engagement in the spat. In Piccoli’s characters there are always at least two selves—an outer self that strikes out at the world with aplomb and confidence and an inner self that crouches diffidently behind the façade, hoping not to be found out, hoping to get away with the deception.

Now Piccoli is hardly the first or only actor to play out the contradictions that inform our outer and inner selves. What Piccoli does that I find so intriguing and so revealing of the contradictory nature of our personalities is to reserve the expression of that other self, that deeper and more pusillanimous self, for those moments of rupture, those breakages in the smooth elasticity of quotidian life that come upon us unawares, that flatten out the contours of our experience and reveal a fundamental void at the core of our being. Where many actors mine every opportunity to grant expression to that secret self (in essence, winking at the audience), Piccoli intuits the falsity of this stratagem. If outward bluster belies insecurity, then the actor must be circumspect in how and when that insecurity is revealed. Piccoli holds back his revelations for those brief flashes that, when viewed closely, seem so out of character for the man he is portraying. Like Paul’s irruptions of violence, these flashes marshal forth a crippled ego that not only lacks self-assurance but also embodies the exact contrary of savoir-faire. The hidden self in Piccoli’s performances knows how to do nothing, is utterly incapable of facing up to the world other than in total despair.

Michel Piccoli and Catherine Deneuve, in Belle de Jour (Buñue, 1967)

Consider, as a rather amusing example, Piccoli’s turn as Henri Husson in Buñuel’s beguiling Belle de Jour (1967). We first meet Henri at a ski lodge. Even though he sits, at first, with only one other person, Renée (Macha Méril), he appears to be holding court at his table in the middle of the restaurant. He is ensconced in his chair—a straight-backed restaurant chair, hardly a vehicle for the stately sense of comfort and self-satisfaction that Piccoli’s Henri exudes—and leans back luxuriously, puffing away at his cigarette. He flirts with Renée in a knowingly sarcastic manner—he tells her he loves her while kissing her hand, assuring her that her scars (perhaps emotional scars inflicted by his manner of love) heal remarkably well. The gesture hits home. Renée pulls her hand away. Henri manages to bridge a distance while ensuring that the distance itself remains adamant. This is seduction that maintains isolation. Henri can say he loves her (and perhaps even mean it on some level) while securing the self from the risk of affection.

Séverine (Catherine Deneuve) and her husband Pierre (Jean Sorel) catch sight of the couple. Séverine can’t stand the penetrating glare Henri turns her way and would rather avoid joining the table but it is too late. Besides Henri amuses Pierre. Henri compliments Pierre in a manner that seems so disingenuous that he feels obliged to insist upon his sincerity. When attractive women pass the table, Henri makes no pretense about his leering gaze. He compares his roguishness to his sympathy for the poor—for him they are all mere expressions of his innate personality. He has the air of a man, wicked in his ways, who revels in that wickedness, who knows the world is corrupt and therefore feels he might as well get his fill of its debauched delights.

But look more closely. That air of smug self-satisfaction, which seems to comport so well with that posture of comfort, is given the lie by Piccoli’s arms. He virtually hugs himself with one arm as he uses the other to hold his cigarette (that cigarette that we come to realize is a talisman for Henri in the same manner that the fedora was a talisman for Paul). His posture of composure is, at its core, mere posturing. The hand with the cigarette gently sways in front of him, conducting his way through his smarmy witticisms. But that other arm braces him, clings to his chest, secures him in his waywardness. He claims a headache is coming on and excuses himself to go for a walk.

Here comes one of those Piccoli flashes in the manner of the imprévu, the unforeseen. Henri remains in his seat a moment too long after he has said goodbye. His gaze lingers on Séverine just a fraction of a second longer than it should have. Pierre, wishing him a good walk, jolts him back to self-awareness. Piccoli does something rather strange here. He has Henri flash a bizarre smile as he stands and places a hand each on the shoulders of Séverine and Pierre. No more words are uttered; he stands and walk off camera, slightly hunched over, as though he were escaping. That smile is so unnatural, so obviously forced that it tears apart any assumption that Henri is self-possessed, self-assured, and removed from the quotidian anxieties of the mere mortals surrounding him. It is simply not the kind of smile the lecherous, smug Henri should have smiled. It is too vulnerable, too insisted upon, too open in its contrivance. If anyone should be surprised by the ending of the film, in which this “man of the world” Henri reveals Séverine’s secret—an act of perfidy without profit—that smile portends the pointless act. For all his seeming self-assurance, Piccoli discloses an Henri who operates from a position of inherent, congenital weakness. It would be untrue to the character (to really any character) to dwell on these moments as an actor and yet they must show up, like flashes of sublime insecurity in a world of banal comfort.

Emmanuelle Béart and Michel Piccoli in La belle noiseuse (Rivette, 1991)

A similar approach to character can be found in Piccoli’s celebrated performance as the painter Frenhofer in Jacques Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse (1991). For all of its tired platitudes regarding the dangerous revelations of truth at the core of authentic art, La Belle Noiseuse devotes a huge part of its running time to a careful depiction of an artist in the humbling throes of labor. Piccoli portrays the painter as outwardly a tired and forlorn craftsman. He lives a comfortable life with his wife and former model (played by Jane Birkin) but clearly regrets never having completed what he expected to be his masterpiece, the painting that shares its title with the film. Having encountered the enchanting but contumacious Marianne (Emmanuelle Béart), Frenhofer decides to take up his brush once again. In an obvious sense, it is a futile gesture and Frenhofer knows it. There is no way to recapture the past. Paths not taken are not the same paths when we return to them. Piccoli communicates the distance Frenhofer feels from the years of his mastery by emphasizing the weight of the corporeal demand of the act of painting for the old man. Frenhofer wheezes with every breath, he can’t find a stool that is sufficiently comfortable (exchanging repeatedly the stool on which his frustrated model is attempting to find her own comfort), his tools require careful positioning, everything feels strange, uncanny, out of place, redolent of a world that no longer exists.

But slowly, as he works, as he devotes himself to the individual strokes of the pen and later the brush, Frenhofer gives himself over not to inspiration but to labor, not to the grand gesture of creation but to the small joy of doing. This is Piccoli’s flash here and, in a way, it is the inverse of his maneuver with Henri. Whereas Henri exudes confidence as a mask for his despairing insecurity, Frenhofer vibrates with obvious regret and disappointment and yet, in ceding the ego to the task, flashes of his former self appear—an old confidence, an old sense of belonging to the world reemerges. For Frenhofer this is both salvation and damnation. The film wants us to believe that the damnation, the curse, resides in the awful revelations of Truth that art unleashes, condemning its viewers to an unwanted and ineluctable insight into the world and their own smallness within it. The childish devotion to such claptrap on Rivette’s part, frankly, ruins the conclusion of the film for me. But the centerpiece of the film, Frenhofer’s slowly unfolding process of both working at the painting and recovering a lost self (even if only momentarily and bitterly and without any hope of a lasting alteration to his current situation), astonishes and enchants me.

Piccoli’s work here is subtle and yet voluble. It speaks of the strained continuity of a life. At times, perhaps most of the time, we relate to our past selves as though they were utterly different people, foreigners who spoke different languages, held different customs dear, had different outlooks and hopes and dreams. We spend much of our lives alienated from our past selves, cut off from whatever projections of a future they held. Our consciousness so often and so steadfastly attends to the present that the past appears in storybook fashion as a legend of some long-forgotten hero whose tales are so steeped in mythology as to appear totally false in the cold light of today. But occasionally, some intimation of that past (perhaps an aspiration set aside, or a passion long since diluted) bursts upon us and the long sequential unfolding of our lives becomes crystalline, if only for a moment. We realize then that the mythology of the self is meaningful, those heroic tales (however banal in reality) are replete with significance, that the self holds together time in a manner that borders upon the power typically reserved for the divine. When we grasp in that flash the duration of the self (the continuity of our lives), we freeze time itself, we hold it in a kind of stasis (the way that God is supposed to understand time—a time that is an object of experience rather than the medium of experience), we become the medium through which time flows instead of our flowing through it.

This inflation of the self never lasts long. It recedes into the onrush of the everyday and we return to whatever narrative of our lives we currently entertain. But for that moment, in that flash, we are divine. This is what, to me, is significant in Piccoli’s portrayal of Frenhofer at work. It is not that Frenhofer, as some exalted artist granted insight into the mysteries of inspiration, has a special purchase upon divinity (its blessed understanding and cruelly incisive insight), but rather that Frenhofer as an old man takes the opportunity to recover the fragile sense of continuity that so determinately evades our grasp and yet is our true access to the divine, to the meaningful, to the cessation of time and the rendering of one’s life a work of aesthetic pleasure and knowledge—that is, the fashioning of a life into a work of art, the Nietzschean aesthetic justification of the world and existence as expressed in The Birth of Tragedy.

As Michel Piccoli approaches his 93rd birthday, these are the lessons I hope to take from him. While plenty of other actors offer up the notion that the self is a construction, that its seams are often showing, Piccoli renders the self as a rather convincing construction and a construction that is often accomplished behind the scenes, even for the person inhabiting that self. The person that we are ought to come as a shock even to us; it was erected, so to speak, behind our backs. The foundations on which the self resides reveal themselves in the fugitive moments of our physical tics (Henri’s out-of-place smile, Paul’s rapping on the statue, Frenhofer’s fervent glare while searching for the right way to position his model), our acting out at a world that we insist underestimates us (Paul’s sudden violence, Henri’s cowardly act, Frenhofer’s petulant glorification of art), our sudden grasping of the continuity of our lives (Frenhofer’s labor, Paul’s winsome look at Camille as she lies naked on the couch—so proximate and yet so removed, a perfect representation of all that Paul hoped to attain and all that he had irrevocably lost)—so beautiful and sad all at once. Piccoli isn’t the emblem of self-possession. Plenty of other fine French actors fit that bill—Belmondi and Jean Gabin, each in their very different manners, are better candidates for that. Piccoli reveals the fissures of the self that lurk behind the self-assured masks we foist upon the world; his is an art not of revelation, per se, but of the hidden reserves that uncannily haunt our quotidian existence.

* * *

The Film Forum in New York City is hosting a retrospective of Michel Piccoli’s work as an actor from Friday 16 March to Thursday 22 March 22. The Forum is showing selections from a wide range of his output, including the films mentioned in this article (Belle de Jour, while strictly speaking not part of the festival, will be shown at the Forum the following week). Highlights of the festival not referenced in this essay include Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid, Marco Ferrari’s Dillinger is Dead, and Godard’s Passion.