Film Strip by joseph_alban (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (2019) is Midge Costin’s directorial feature debut. Bringing together film clips and verité footage, she weaves these together with her interviews with leading directors, amongst them: George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, David Lynch, Ang Lee, Christopher Nolan, Sofia Coppola and Ryan Coogler, as well as Oscar winning sound designers Walter Murch, Ben Burtt and Gary Rydstrom. The documentary gives voice to the often under-appreciated story of cinematic sound, one lost behind the smoke and mirrors of film as a visual art form.

Opening with Rydstrom’s work on Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg, 1998) and the emotional impact of sound, she then builds the story around Murch’s work on Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979). This sets the tone of a documentary divided into chapters, breaking down the diversity of sound present in cinema.

In the 1990s, Costin worked as a sound editor on some of notable blockbusters produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson: Michael Bay’s The Rock (1996) and Armageddon (1998), Tony Scott’s Days of Thunder (1990) and Crimson Tide (1995). In addition to her blockbuster credits, she was the dialogue editor on John Waters’ Cry-Baby (1990) and sound editor on Kenneth Branagh’s Dead Again (1991). Outside of her film work she has lectured at The University of Southern California School (USC) and lectures internationally on her industry experiences.

In conversation with PopMatters, Costin talks about her early ambivalence towards sound, how collaborative filmmaking has propelled sound in film forward, and the challenges of integrating the chapters of the story of sound into a single film.

Recording Pooh the Bear for Chewbacca (Photo © Karen Johnson and Bobette Buster) (Courtesy of Dogwoof Films)

It’s a commitment to make a film, requiring you to devote a period of your life to it. What compelled you to believe in this project and to tell this story?

…When I studied film at graduate school I really didn’t like sound; it seemed very technical. I wasn’t relating sound to story and character, and I came out wanting to be an editor. But I still had my thesis film left.

I did an apprentice and an assistant editing job on a film. Then a friend called me up and said that none of the union guys would work on 16mm sound, and he’d teach me how to cut. I took that job because I needed the money to finish my thesis, and I really saw it as lowering myself from a feature editor.

Then when I started to work on that film I realised, ‘Oh, I’m responsible for setting a mood and a tone with the sound.’ And, ‘How am I going to say something about character or plot point?‘

So I started to work on the story with sound, then I went from one job to another. The next thing I knew I was working on these action adventure movies, which was fun because I was cutting effects. It was in the late ’80s and the ’90s, and we were doing surround sound, so it suddenly became fun, and I was using sound in a much more interesting and emotional way…

I realised when I was in school that I just didn’t have the knowledge. So I was interested in trying to let young filmmakers know that you can use sound to help tell the story. The directors see sound as fifty percent of their films, and working as a sound editor and sound designer, I was feeling that people really didn’t appreciate or understand sound at all. So in 2002 I tried to do the movie then, but there was no such thing as fair use where you could use copyrighted material, and it would have been too expensive.

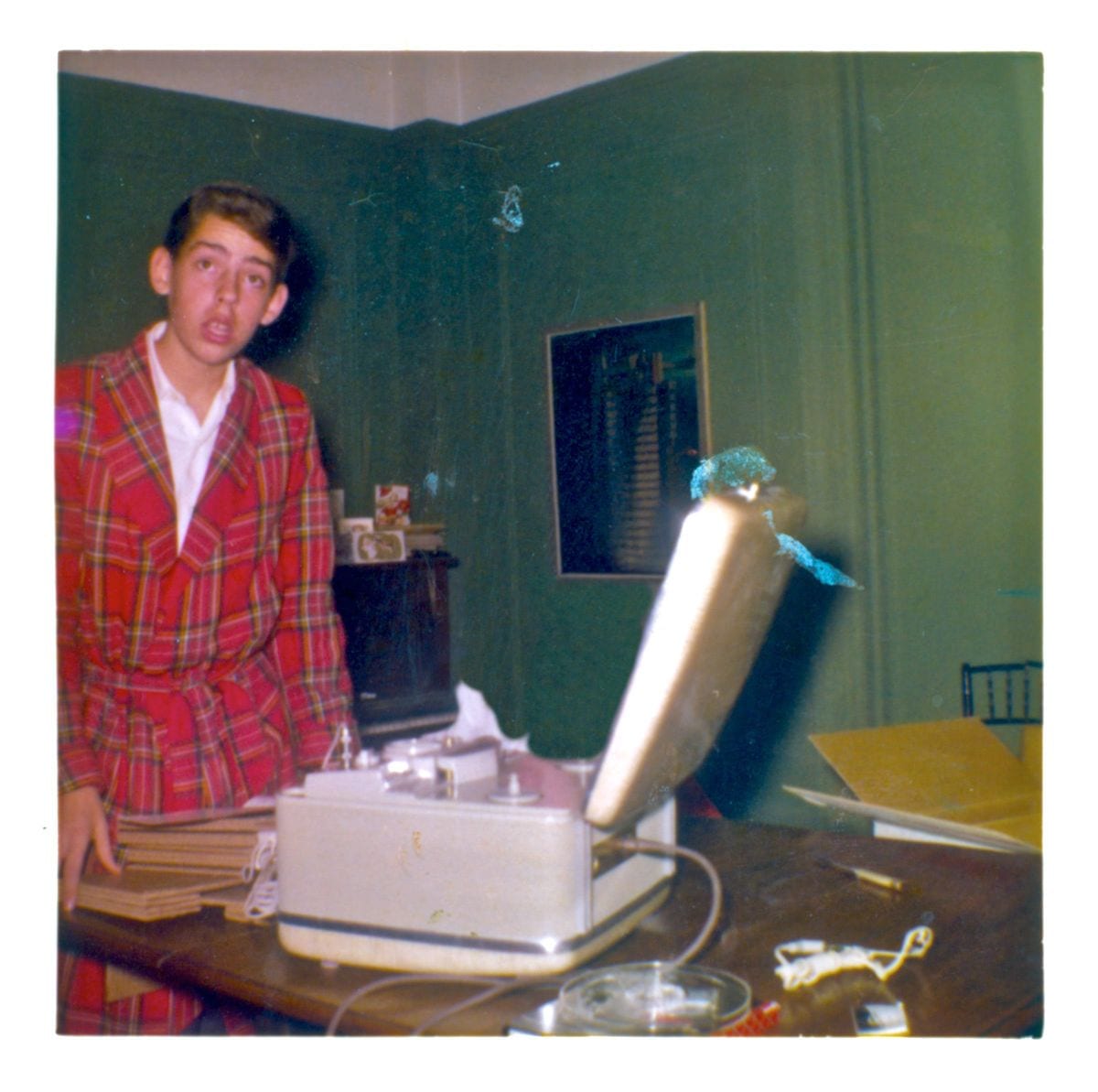

Walter Murch gets a sound-mixing machine. Christmas 1957. (Courtesy of Dogwoof Films)

So what happened to us in 2010 is my producing partner, Bobette Buster ,talked to Garry Rydstom, whom she knew at Pixar. She asked him if he would help. He said he’d be involved and told her, “You should speak to Midge Costin.” So that’s where we started. In 2010 we began to write it and to think about how we’d do it…

Cinema is often referred to as a visual medium, yet this description only serves to undermine the art form. While it draws on the literary and is an offshoot of other mediums, dialogue, sound and music are also integral to the film as an audio-visual experience.

When I started teaching at USC, because I was so interested in telling young filmmakers about sound, the first thing I noticed was that they described all the classes as visual storytelling. I asked them, “Could we add the word oral to every single class descriptor?” And they did because they realised it was true; it’s not just sound for sounds sake, it’s sound with picture.

A lot of times I would look at the picture and then I would gather or record the sounds and I’d think, ‘Oh, this’ll be perfect for it.‘ But then you’d put something up against the picture and it’s not what you thought it was going to be. So it’s all about the chemistry of them working together, and it’s a unique art form in that way.

As you say, there are so many things — the rhythm and the pacing, and it’s almost like dance. Then there’s music and there’s performance, all of that. It’s why I also wanted to break down the different types of sounds people could hear: foley, dialogue editing, and ambiences. I think it’s important that people understand and start thinking about sound in their lives too.

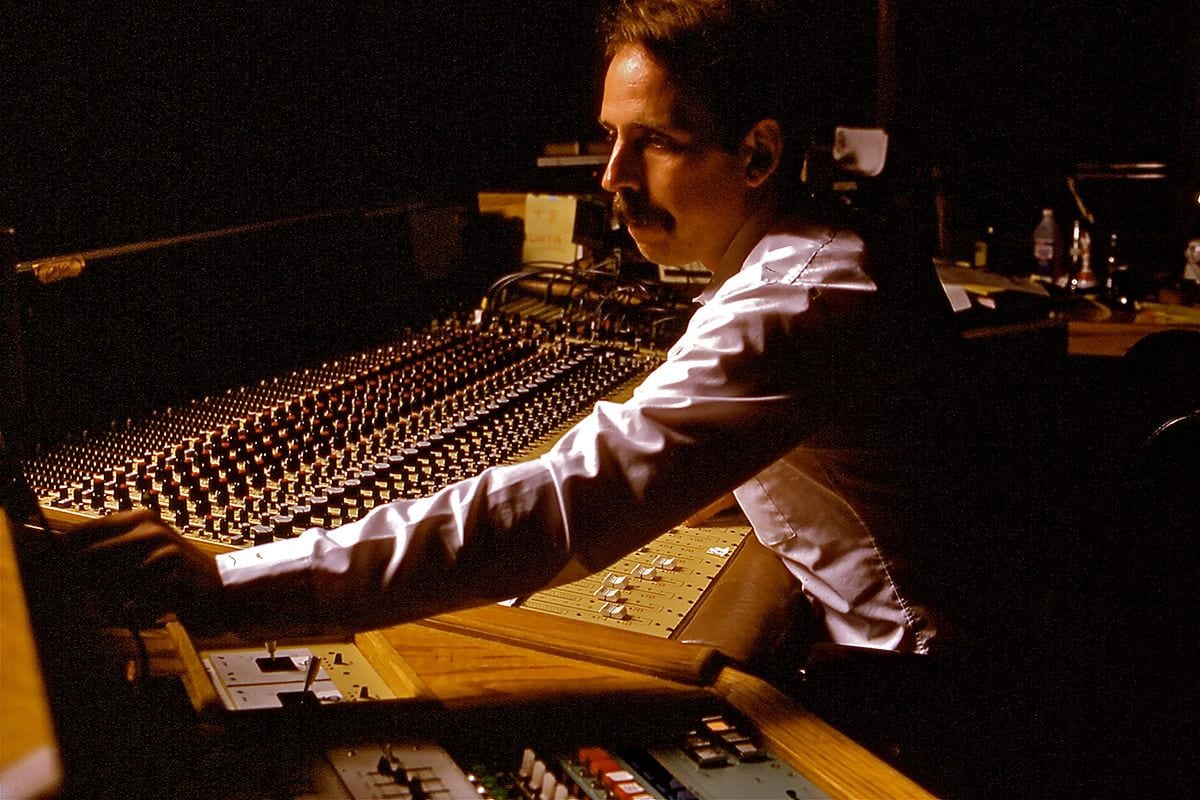

Walter Murch mixing Apocalypse Now (Courtesy of Dogwoof Films)

The documentary not only looks at the direct collaboration between filmmakers and sound designers, but also the indirect collaboration that has unfolded over a long period of time through the work of Al Jolson, Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas. Front and centre of your documentary is the role of collaboration as an impetus for developing the alchemy of sound and picture.

One of the ways that I got the directors to interview was through the sound people, because they so appreciated the collaboration with them, and what they bring to their movies. You can see where the big changes happened, or the innovations that came when George Lucas was working with Walter Murch back at film school. But then Murch was given a lot of time on the Francis Ford Coppola films because there was a lot of collaboration back and forth.

Remember too, there’s the part about George and Walter working together on THX 1138 (Lucas, 1971). Both talked about how on THX, George would work in the day and Walter would come in every night to do the sound, and then it would change the picture based on the sound. So they worked day and night together, and it was the artists working together that pushed the film forward.

…The other thing is even just looking at all the different types of sound people. We all have to work together. I tell my students this. I remember I used to come in at 10am in the morning, but most people would come in at 8 or 8:30am. I realised I needed to be there so that the foley editor and I could talk to each other about how we were covering a scene, or in what frame something happened. Where did the punch really happen?

You are collaborating closely, so you just need to be there at the same time. You can see George Lucas asking Ben Burtt to come on a year before he even started shooting [Star Wars, 1977] – that’s when the best stuff happens. So too with Skip Lievsay. When he works with the Coen Brothers, he reads the script along with Carter Burwell, their composer, and then they talk about who’s going to cover what before they [the Coen Brothers] even start to shoot.

All of that is so important, and that’s where you get the best sound. I think the best films are when people are collaborating early on together…

Documentary filmmakers are forced to sift through and condense a mass of footage to form their final film. How closely does the final cut of Making Waves mirror your original intentions. Also, was the project one of close collaboration with your editors to discover its final form?

This was difficult to do because we shot 90 interviews, so that was crazy. It was 200 hours of material and I knew that I wanted to do a 90-minute movie. We knew at some point we would probably do the history, and we knew in the history we would be able to cover certain people that were going to be important within the story. That was the easy part. But I can’t tell you how long it took us to figure out how to integrate the different types of editing and mixing into the story. It would be weird to start out with silent movies when it’s a film about sound, so we were trying to figure that out too.

…My editor [David J. Turner] was a former student of mine. He was a student when he started this film [laughs], and so that’s how long it was. …Working with him I would do notes and paper cuts, and then he would make them much more poetic. But in the last two years we had Tom Miller, who was a supervising editor, and that was necessary to figure out, how do we pull these different parts together? I still don’t know how we did it.

I think it that’s circle of talent we were able to put up near the beginning of the film for Saving Private Ryan, and then build it around Apocalypse Now. …But it was difficult to put together and it took a long time for it to feel like one movie.

The interview content left on the cutting room floor likely offers interesting observations and also add to the story. Is the process one of accepting the difficulty of making these necessary choices, which is perhaps lost on the audience?

Well we are hoping that we’ll either do a series. We could do a great one going into much more detail. I’m going to save all of it so we have it, because there wasn’t all that much that we could find in the archives for the first generation of sound. I wanted to make sure that we really captured the second generation of sound, even if we just put it in The Academy Museum so that people can access it.

I want people to be able to access these interviews because I have four hours of Walter Murch, Ben Burtt and Gary Rydstrom. I think it may even be a three hour interview with George Lucas. I am hoping that we will be able to make this accessible to people, or maybe before we do that, someone would want us to do a series.

It was hard and I felt like you said, people don’t realise. It’s the old “killing your babies” – you’ve got to figure out what you’re going to take out [laughs]. There’s so much great material and I just knew that I wanted to capture as much as we could while we had these persons. So I feel okay about that, but it was difficult to cut it down to the 90 minutes.

I also feel that it’s important to have a general audience understand and appreciate it. We can always go into more detail [later], and that could be for film schools or film lovers…

Does the story of sound still have these big evolutionary chapters ahead, or must we question whether there is a point at which evolution reaches its conclusion?

…One of the reasons I wanted to put Alfonso Caurón’s film Roma (2018) in at the last minute was because I felt that he was doing something different. When I spoke to Ben Burtt — and maybe even Walter, but I remember Ben thinking nothing had been done that was new — and feeling it was about time something broke loose. I thought it’s not hugely different, but we’ve been very conservative in what we use in surrounds and the immersive sound. Alfonso was pushing even dialogue in the surrounds. It’s a much more immersive theatre than we’re used to using. I thought that was important.

…I honestly feel that not as many people go to the theatres, so they might be hearing it in stereo or on headphones. I don’t know, I’m not a very good predictor of what’s going to happen, and I’m not sure anyone talked about that. But because of virtual reality in games and interactive stuff, it’s going to be more and more immersive. The headphones that are being developed are more along those lines, but it’s hard to say.

Filmmaker Christoph Behl remarked to me: “You are evolving, and after the film, you are not the same person as you were before.” Do you perceive your work in sound to have had a transformative effect on you?

…What I’ve learned to do is listen, and to also have awareness about how I’m being affected by it. We are very much affected by sound in our environment, not just in art, in movies or music, but in our everyday lives, like sitting in restaurants and being in the world. And now working in sound, I feel like I have more awareness. It’s really hard for people to acknowledge that and everyone thinks they are getting all their information through the visual…

So I feel it has been transformative and I’m so happy to be in sound. Maybe I wouldn’t feel that way if I’d stayed in picture editing. But I feel like it has brought so much to my life.

The other thing I noticed just working on picture, and I said it before, but sometimes at the spotting session where you look at the picture and you make notes, then you either go to your library or you go out and record stuff, it’s like, “Oh, this is going to be the perfect sound.” Then when you put it against picture it’s, “Oh, it wasn’t that sound, it’s this other one.”

There’s just some kind of alchemy between picture and sound that’s so interesting. You never know what it’s going to be exactly. That has been fun to think about, how to use sound artistically. It makes you think about how you are affected by low frequencies and higher frequencies and how they work together.

Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound was released in the US on 25 October 2019, and in UK cinemas and on Digital 1 November 2019. It will be available on DVD from Dogwoof Films (UK) on 25 November 2019.