When someone tries to tell me about some recent movie that they feel is “edgy” or “daring” or “unsparing”, I have to bite my tongue from cutting them off to ask “How does it compare to Midnight Cowboy?” It’s sort of like the Godfather rule for rating films—if 10 is the highest score, you don’t give any new film a 10 unless it’s at least as good as The Godfather (or whatever film you think is the greatest of all time). Along the same lines, don’t tell me about how superbly a film provokes the bourgeoisie or portrays the bleakness of life unless it does so at least as effectively as Midnight Cowboy. And don’t tell me about how the Oscar voters are going out on a limb this year unless they’ve done something at least as surprising as they did in 1970 by choosing this X-rated film for Best Picture.

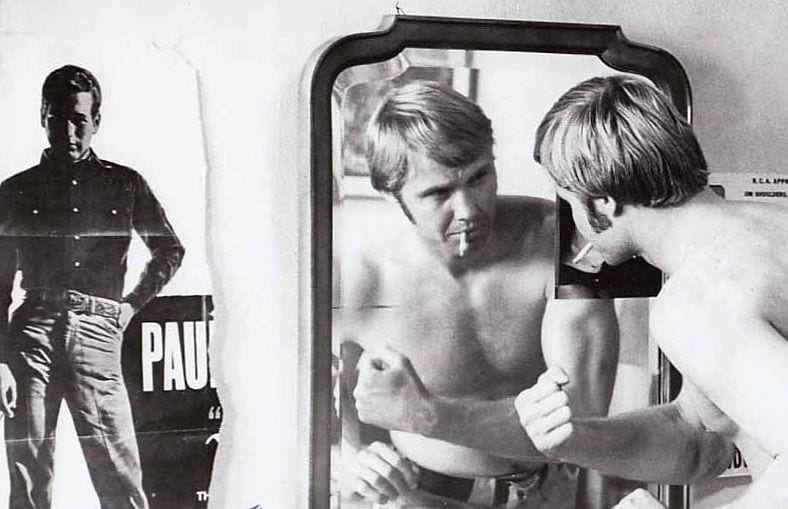

John Schlesinger‘s 1969 film, based on a novel by James Leo Herlihy, portrays the fortunes of Joe Buck (Jon Voigt), a handsome but dumb as a rock young man who takes the bus to New York City to seek his fortune. Joe was a dishwasher in Texas, but believes that decking himself out in the Hollywood version of cowboy duds (packed in a black-and-white cowhide suitcase, the likes of which you’ve probably not seen or since) will somehow make him irresistible to rich women in the big city, who will therefore be willing to pay him for stud services His first such encounter (played with maximum hilarity and furor by Sylvia Miles) doesn’t go well—in fact, he ends up giving her money—and soon he’s just another broke dude without a clue about how he’s going to survive.

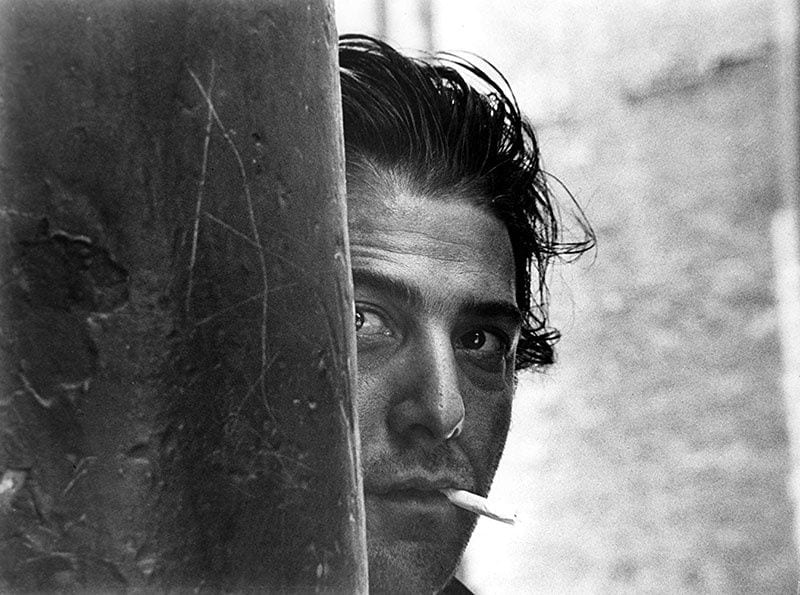

Fortunately, Joe meets up with someone who has learned the survival skills he lacks—Enrico Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), better known as “Ratso” (a peculiarly appropriate moniker, since urban rats are perhaps the champion survivors of all time). Flashbacks fill in Joe’s background, fantasy sequences suggest his dreams for the future, and in the present day he and Ratso have some very New York City adventures. One of the most interesting is their attendance at a party that might have been staged by Andy Warhol, where joints are smoked, drugs are ingested, and Joe completely loses his bearings. Without spoiling the ending, I’ll just say that this is no fairytale and the way it all ends up is pretty much what you might expect would happen were the characters living in the real world. Although it has been interpreted as such, Midnight Cowboy is not a condemnation against the impersonality of city life so much as it is a cautionary tale for those who mistake their illusions for reality and refuse to adjust when those illusions are exposed for what they are.

Midnight Cowboy makes a strong argument for location shooting—while this film would be excellent no matter where it was shot, the fact that it captures aspects of Times Square before the arrival of Walt Disney and the Hershey store gives you one more reason to watch it. Granted, some scenes are not set where they appear to be (fun fact: the “leaving Texas” sequence was shot in New Jersey), but the New York stuff is as real as it gets on screen. The characters are types that remain familiar to city dwellers, and Ratso’s “I’m walking here!” outburst holds a particular fond place in the hearts of urban walkers everywhere (no idea how it plays among those who grew up in the automobile-centric suburbs). Another aspect that will ring true to urban dwellers is the casual contact between rich and poor on the city streets, which doesn’t diminish the gulf between the lives led by members of different economic classes.

Despite its accurate portrayal of life in pre-gentrified New York, much of Midnight Cowboy is quite stylized. Cinematographer Adam Holender, shooting his first Hollywood film, uses every trick in the book to portray Joe’s state of mind as well as his physical surroundings, while clips from contemporary films and TV shows help establish the cultural context. The eclectic soundtrack plays a key role in establishing the shifting moods of the film; besides some original material by John Barry, the soundtrack includes Nilsson’s cover of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin'”, “A Famous Myth” and “Tears and Joys” by the Group, and “Jungle Gym at the Zoo” by Elephant’s Memory. Both cinematography and soundtrack are well-served by this release, which was created from a 4K digital restoration of the 35 mm film negative and a remastering of the original monaural soundtrack.

The illustrated liner notes include an essay by film historian Mark Harris, while the disc includes a commentary track by Schlesinger and producer Jerome Hellman as well as a number of short films. The latter include a conversation with photographer Michael Childers, Schlesinger’s life partner and assistant on Midnight Cowboy (14 min.); a video essay by cinematographer Adam Holender (25 min.); the 1969 short documentary “The Crowd around the Cowboy,” directed by Jeri Sopanen (9 min.); the 2004 documentary “After ‘Midnight’: Reflecting on a Classic 35 Years Later” (30 min.); a 2000 interview with Schlesinger and excerpts from the 2002 BAFTA tribute to Schlesinger (15 min.); a 1970 David Frost interview with Jon Voight (14 min.), the 1990 documentary Waldo Salt: A Screenwriter’s Journey, directed by Eugene Corr and Robert Hillman (57 min.), and the film’s trailer (as sanitized as you would expect, since it would have been shown before films more suitable for a family audience).

- Midnight Cowboy (1969) - Rotten Tomatoes

- The film that makes me cry: Midnight Cowboy | Film | The Guardian

- John Schlesinger winning the Oscar® for Directing "Midnight Cowboy"

- 15 Uncensored Facts About 'Midnight Cowboy' | Mental Floss

- Midnight Cowboy (1969) - IMDb

- The Criterion Collection - Midnight Cowboy(1969)