For ten months, Mike Mills edited his latest film, C’mon C’mon, alone, at a desk at home.

“My editor Jennifer Vecchiarello was in a little chat window on my computer screen,” he recalls. Locked down at home in 2020, Mills poured his heart into the film, which in many ways couldn’t be more personal.

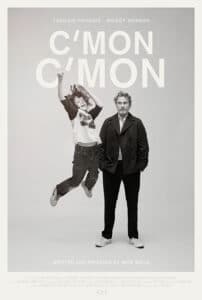

C’mon C’mon is about a radio documentarian named Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix) who brings his nephew Jesse (Woody Norman) on a cross-country work trip while his sister Viv (Gaby Hoffman) attends to her ailing husband. Uncle and nephew get to know each other on an intimate level, pushing each other’s buttons, learning life lessons, and developing a bond that neither of them knew they so desperately needed.

Many of the scenes pull directly from Mills’ relationship with his son, making the story authentic. Nervous to share that part of his life with the world, he went into the film’s first festival circuit screenings not knowing how audiences would react to, essentially, scenes from his life. He was moved and relieved to find that his quiet little film had a powerful impact.

“I guess it’s the highest compliment. I guess it’s the thing I want the most,” says Mills of the positive reception to the film. “It’s the most meaningful thing, and when you talk about fathers feeling a sense of recognition…that’s gorgeous. What more could you want? I communicated about something really dear to me, and people heard.”

PopMatters was invited to a screening of the film this past October at the Mill Valley Film Festival, and it was difficult to spot a dry eye in the house by the film’s end. Phoenix and Hoffman are sensational onscreen, but it was Norman who seemed to leave the biggest impression on the festivalgoers.

Norman was nine years old at the time of filming and is, without an ounce of exaggeration, one of the best, most natural onscreen partners Phoenix has worked with. According to Mills, Norman’s performance went above and beyond what any filmmaker could hope for from a relative newcomer. “He would cry on every take, at the same line,” says Mills of a particularly juicy, dramatic scene in the film. “That is a fucking actor. He can cry whenever he wants, and it’s not fake. It’s not a bad cry.

“It’s almost too much pressure on poor Woody, how impressed everyone is,” Mills continues with a smile. “His performance came about in such a nice, light way. There wasn’t any haranguing at all. He’s just really smart and really funny. The less you tell him what to do, and the more you let him choose what to do, the more gold you’re going to get. He’s an amazing actor.”

The real-life chemistry between Norman and Phoenix translates beautifully in the film. “Joaquin and Woody had a lot of fun together,” says Mills, who describes C’mon C’mon as something of a fable about parenthood. Phoenix and Norman’s adult-child silhouette informed everything about the film’s stylization, from the imagery to the sound, to the editing.

C’mon C’mon unfolds like someone thumbing through a book, sometimes fast, sometimes slow. At times, we see a series of fleeting moments from the characters’ lives rush by in quick succession – we can’t hear what they’re saying, but there’s a “real life” quality to the scenes. “I think the ephemerality of childhood is doubled down by the ephemerality of film,” says Mills of the filmmaking style he employed for C’mon C’mon. “A film is a uniquely perfect way to talk about [that ephemerality] because it *woosh*…just goes by. The medium really helps the message.”

Mills uses unique cinematic devices to bring C’mon C’mon to life, like the film’s black and white presentation, and the unscripted interviews between Phoenix and non-actor children that are interspersed throughout the film, complementing Johnny and Jesse’s story in poetic ways. His fascination with and passion for the medium is palpable. “Films are in the realm of magic. They just fucking are,” Mills beams. “They’re a dream space that you share with people. What a weird thing to sit in a dark room and watch images go by as a collective thing. It’s, like, part of the dark arts or something [laughs].”

Though the film may appear to be a low-key cinematic affair as far as production and effects are concerned, there is actually a fair amount of “movie magic” going on that audiences may not pick up on consciously but that Mills and his team spent copious amounts of time and effort on to achieve something truly poignant. The black and white imagery, for example, opened Mills up to a new world of sound design, to his surprise.

“The thing about black and white is that it absorbs sound,” Mills explains. “It’s some neurological thing where, when the color channel is gone, your brain fills it with sound or something. I don’t know what I’m talking about [laughs].”

But of course, he does know what he’s talking about, and he and his sound team pair sound with imagery in a strange and beautiful way in the film. In a nerve-racking scene in which Johnny loses sight of Jesse in a convenience store, Mills and his sound team use crafty techniques to build tension and anxiety.

“When Johnny loses Jesse, there’s a phone ringing,” he explains. “And it gets louder and louder. It’s grating, like a siren. In color movies, it would sound too obvious. But in black and white, you need the sound to fill up that space. There’s so much sound in the movie. So much foley and I never do foley. There are so many background layers, and the movie is just jam-packed with sound…but as an audience, we don’t experience it that way.”

While most of the film is set in small, intimate environments, there were a couple of scenes that required a bigger, more elaborate production crew than Mills was used to working with. A parade scene in New Orleans involved 400 extras, and a pivotal scene in New York City, in which Johnny loses Jesse in a crowded street, required 300 extras, two cameras, and a city bus. “It was really fun to switch into that mode,” Mills recalls. “It was almost like a stunt day. Everything was really planned, like a military operation.”

But like every other artistic decision in the film, the more elaborate setup serves a purpose. Mills wanted the scenes where Johnny would lose Jesse to completely disrupt the flow of the story because, in real life, losing your child has precisely this effect.

“It happens to everyone who has a kid,” he explains. “Everything’s nice and easy, and then…BOOM. Something big is happening. It’s like an action movie all of a sudden. The kid can hurt themselves, or you can lose them. I wanted the film to be really gentle, and intimate, and relational, and then WHOA…something really big happens. To me, that feels accurate to being a parent.”

Mills feels a deep sense of gratitude for the sincere, positive reception C’mon C’mon has garnered thus far. As audiences and critics alike heap praise on the film, he seems reluctant to take credit for its success himself, citing instead the unique timing and tone of the film as one of the main reasons it’s resonating with audiences.

“I’m really benefiting from this moment in history in a way that was so unpredictable,” Mills says, referring to the film releasing as America begins to open up once again following the pandemic lockdown. “We’re all so excited to be together… We’ve all had our own versions of a very hard time, and we’re all a little tender. Maybe because of this moment in history, this movie makes you feel vulnerable, not unlike being a parent. To have the movie be in sync with how people are feeling right now makes me feel very lucky.”