Are we more concerned with the size, power and wealth of our society or with creating a more just society? The failure to pursue justice is not only a moral default. Without it, social tensions will grow and the turbulence in the streets will persist despite disapproval or repressive action. Even more, a withered sense of justice in an expanding society leads to corruption of the lives of all Americans. All too many of those who live in affluent America ignore those who exist in poor America; in doing so, the affluent Americans will eventually have to face themselves with the question that [Adolf] Eichmann chose to ignore: How responsible am I for the well-being of my fellows? To ignore evil is to become an accomplice to it.

– Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

In case you missed it, a major player in the Civil Rights Movement recently passed away — and frankly, you probably did.

Dorothy Cotton was the only woman on the executive staff of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the organization founded by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other ministers in 1958 to build on the success of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott in continuing the fight for black civil rights. She served as SCLC’s director of education for 12 years and was a close confidant to both King and his wife, Coretta Scott King. Later in life, she continued her social justice advocacy with the Dorothy Cotton Institute, an incubator for activists established by the Center for Transformative Action at Cornell University.

If it seems a bit reductive that the previous paragraph led off with the phrase “the only woman”, such status seemed to rankle her a bit when I met her 40 years ago this summer. That was during my internship at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, learning about King’s life and work and strategizing how to carry it forward. (I’ve written about that moment twice before in this space.)

Briefly: there was something of a generational conflict between us interns and our teachers, wanting to finish the work King and his cohort started, and Cotton and many of the movement veterans, who wanted to make sure we knew about all of the shoulders we were standing on. To a large extent we were talking past one another, as often happens in generational conflicts. But what was key, I see now after all these years, is that these movement veterans were all women, and their names or contributions were not foregrounded in our study of the movement at the time.

The word “gendered” wasn’t much used back then, but in retrospect, that best describes what was happening. In the rush to celebrate King and lift up many of the other (beyond deserving) men whose names and images would be forever linked with the freedom struggle, Cotton implored us to remember the people behind the headlines, deep in the trenches, doing the important rubber-meeting-road work that fueled the movement, and becoming leaders themselves as a result. And yes, many if not most of the figures she and her colleagues wanted us to know about were women.

In time, the gender imbalances of the movement hierarchy would become better known, and we would get a better sense of the contributions Cotton and other women made. But even that layer of additional insight didn’t uncover a broader truth: the post-World War II iteration of the black American freedom struggle was more than sit-ins and marches, and like other revolutions, most of it was not televised.

So Jeanne Theoharis‘s A More Beautiful and Terrifying History comes at a most opportune moment. First, Cotton’s passing should remind us that only a few voices from the frontlines are still with us, and we ought to make sure we capture their stories while we still can if we haven’t already done so. In fact, the book informs us that there are more stories to tell about the movement than the ones we think we know. Theoharis amplifies what Cotton was trying to tell us, even more broadly than she was aiming at. Not only was the struggle bigger than King, it was, in fact, bigger than the whole damned South.

There are two main points inside A More Beautiful and Terrible History. The first, which various others have taken up over the years, is that King’s work as a forward-thinking crusader has been largely whitewashed, with the most radical planks of his vision subsumed by a misdirected, Kumbaya-colored reading that all he wanted was for everyone to live in peace and eat at the same lunch counter. The second is that he was far, far, far from the only one saying such things.

To this first point, I’m afraid I gave horribly short shrift in my previous reflections to that summer’s main text. We interns were assigned his last (as it turned out) book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (Beacon, reprint, 2010) It was written in early 1967, while King was vacationing in Jamaica with Coretta and close associates. Its publication that spring coincided with his April 4, 1967 speech, “Beyond Vietnam“, at the Riverside Church in New York City, in which he decried not only the Vietnam War but also militarism in general (more than once during my internship, it was noted that he was killed exactly one year to the day after that speech).

Indeed, Where Do We Go From here is a wide-ranging work, taking stock of the gains made in the previous 12 years since the Montgomery bus boycott, King’s entrance into the ever-flowing river of black resistance, and surveying the current landscape. It expands upon many of his speeches and articles from the previous two years, in which the triumphs of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act only freed King to address even more intractable issues.

By that time, barely ten years after he was killed, the far-ranging vision of his beliefs was already being lost to history (indeed, much of the King Center’s work back then was ensuring that his true intent would continue to burn in somebody’s heart somewhere). To that respect, Where Do We Go from Here? read like fire, as if we were being given an alternate vision of the world that time had conspired to hide forever and a day:

The stability of the large world house which is ours will involve a revolution of values to accompany the scientific and freedom revolutions engulfing the earth. We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing’-oriented society to a ‘person’-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered. A civilization can flounder in the face or moral and spiritual bankruptcy as it can through financial bankruptcy.

And:

The curse of poverty has no justification in our age. It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization when men ate each other because they had not yet learned to take food from the soil or to consume the abundant animal life around them. The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty.

And:

And so we shall have to do more than register and more than vote; we shall have to create leaders who embody virtues we can respect, who have moral and ethical principles we can applaud with an enthusiasm that enables us to rally support for them based on confidence and trust. We will have to demand high standards and give consistent, loyal support to those who merit it. We will have to be a reliable constituency for those who prove themselves to be committed political warriors on our behalf. When our movement has partisan political personalities whose unity with their people is unshakable and whose independence is genuine, they will be treated in white political councils with the respect those who embody such power deserve.

(Okay, maybe that last sentence was a bit optimistic, given the Fox News-ification of American politics that was nowhere near the horizon when he wrote that, but still.)

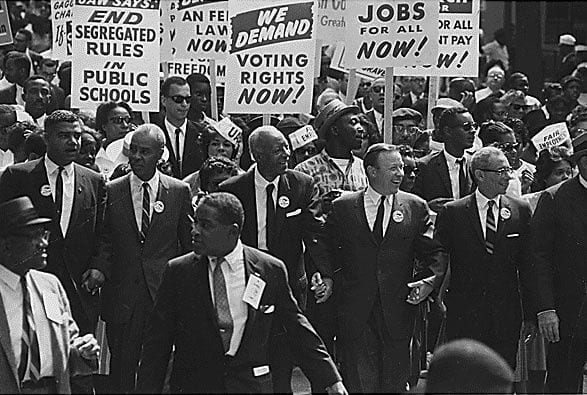

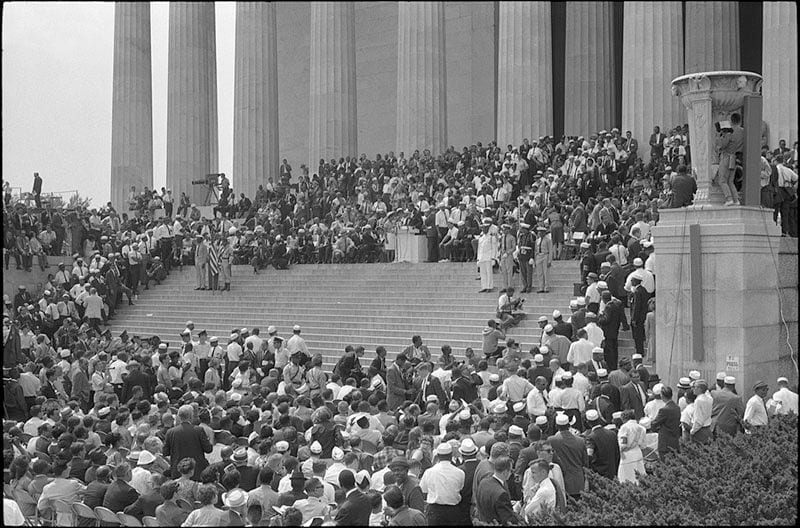

I remember a whole world opening up as I read that book. I’d never imagined King to be that radical. In fact, I had little idea what had happened between the 1963 March on Washington, the occasion of his Mahalia Jackson-prompted riff that became the “I Have a Dream” speech, and his murder five years later. So everything I learned — his battles with Northern white racism in Chicago in 1966, his opposition to the Vietnam War when other black leaders cautioned him not to go there, his nuanced opposition to Black Power militancy — was one revelation after the next.

By then, though, the casting of King as simply a man of racial reconciliation had already begun. In fact, it had started not long after he’d been buried. Dion’s song “Abraham, Martin, and John”, a hit soon after both King and Senator Robert Kennedy were killed, may have unwittingly set a tone for the reduction of King’s intentions, in its toothless evocation of King’s work:

Has anybody here seen my old friend Martin,

Can you tell me where he’s gone?

He freed a lotta people, but it seems the good die young

But I just looked around and he’s gone.

Even Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday,” his 1980 rallying cry for a national holiday commemorating King, reflects a softened version of his impact:

We know the key to unity all people

Is in the dream that you had so long ago (happy birthday)

That lives in all of the hearts of people (happy birthday)

That believe in unity (happy birthday)

We’ll make the dream become a reality (happy birthday)

I know we will (happy birthday)

Because our hearts tell us so (happy birthday)

In time, schoolchildren could not be blamed if all they knew of King was that dream he had, and not the earlier part of that speech, in which he railed about the bad check America had written promising equality for all. The true weight and extent of King’s vision was all but buried, to the point where conservatives who never would have dreamed of joining his cause now eagerly appropriated an image of King shorn of his fire.

Early on, Theoharis picks up the baton:

By stripping King and [Rosa] Parks of the breadth of their policies — which interwove economic justice, desegregation, criminal justice, educational justice, and global justice — many of these national tributes render Parks and King meek and dreamy, not angry, intrepid, and relentless, and thus not relevant or, even worse, at odds with a new generation of young activists. These memorials purposely forget the decades when these activists were surveilled, harassed, ostracized as troublemakers, and upbraided as ‘extremists’ — how part of the way racial injustice flourished was through the demonization of those who called it out… By holding up a couple of heroic individuals separate from the movements in which they were a part, the ways the era is memorialized implicitly creates a distinction between the people we have today — too loud, too angry, too uncontrolled, too different — and the respectable likes of King and Parks.

Such righteous indignation flows freely throughout the rest of the book. Not unlike Howard Zinn‘s A People’s History of the United States, Theoharis expands our understanding of the nature and extent of racial justice activism beyond signature moments like Birmingham in 1963 and Selma in1965, but with a more analytical mindset than merely fleshing out the historical record. In the process, she reveals not only how far-reaching the struggle was, but also the ends its opposition would pursue, and lessons today’s activists can draw from that experience.

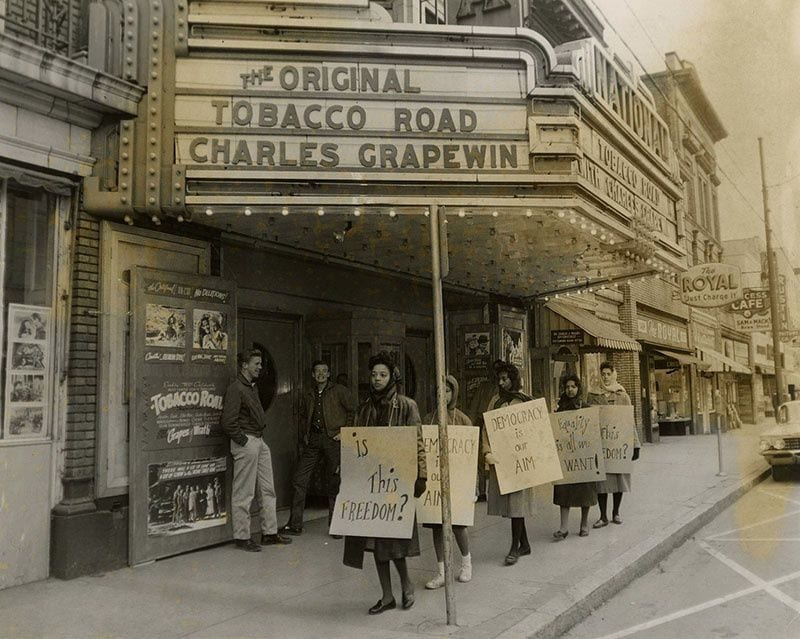

Theoharis recounts the mid-’60s battle for school desegregation in New York City, a moment not noted in the popular version of civil rights history from that era (there was a similar movement in Chicago around the same time). She traces the city’s reluctance to abide by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in both letter and spirit, and introduces us to the parents who launched a school boycott in 1958, and a much larger one in 1964, to protest substandard and unequal conditions. Yet, she asserts, while white liberal Northerners were quick to poo-pooh the South for its blatant practices, they turned a blind eye to the equally unfair goings-on in their midst. As a result, and thanks to some questionable carve-outs in the legislation that became the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the boycott didn’t result in any major change in NYC schools.

Similar dynamics played out after the 1965 Watts riots in Los Angeles, and the long slog of school desegregation in Boston in the ’70s. In both cases, there was little civic appetite to consider that what was happening in those cities might be parallel to the very issues Southern activists were confronting. The media attention paid extensive attention to the South, but hardly any to all to Northern-style racism. Theoharis’ examination of these events brings to mind the bemused observer in Randy Newman’s “Rednecks”:

Now your northern n*****’s a negro

You see he’s got his dignity

Down here we’re too ignorant to realize

That the North has set the n***** free

Yes he’s free to be put in a cage

In Harlem in New York City

And he’s free to be put in a cage

On the South Side of Chicago

And the West Side

And he’s free to be put in a cage

In Hough in Cleveland

And he’s free to be put in a cage

In East St. Louis

And he’s free to be put in a cage

In Fillmore in San Francisco

And he’s free to be put in a cage

In Roxbury in Boston

They’re gatherin’ ’em up from miles around

Keepin’ the n*****s down

Theoharis deploys the frame of “polite racism” to describe how the phenomenon happened. “Segregation flourished in part because ‘polite’ people stood back to make room for it,” she writes. “When movement activists used desegregation of schools and housing and jobs, some people attacked, but others stood by and let them attack.”

But that might not be entirely those folks’ fault: it’s not as if mainstream news media showed much interest in covering opposition to the racial status quo, a condition Theoharis notes hasn’t much changed despite the role of social and alternative media in giving voice to the present-day struggle. “Such silences are comfortable,” says Theoharis. “It is easier to castigate protesters as ‘thugs’ unwilling to work through the proper processes than for media outlets to hold accountable neighbors and public officials who didn’t listen when they had.”

Time and again, Theoharis stresses that the dominant images of the black freedom movement — King and Parks as mild-mannered people, Black Power activists as racial demagogues — do not square with the actual nature of their stances and actions. Of Black Power, she writes, “But there’s a convenience in making Black radicalism all about the guns and leather jackets because it obscures the larger goals for social, political and economic transformation that ran through the Black freedom struggle and the deep resistance Black activists encountered.”

She goes on to challenge the Great Man-ification of civil rights history. First, it was a young people’s movement in many respects, with high school students taking the lead in several schools desegregation battles of the ’50s and ’60s. Second, women were very much at the core of the movement, and not just as administrative helpers and housewives. Theoharis cites her previous Parks biography, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (Beacon, 2013), to remind us that she was anything but a tired housekeeper who unwittingly launched a movement. She also reminds us that Coretta Scott King was an activist for numerous causes in her own right long after her husband was murdered, a point to which I can attest: during my King Center internship, the hot-button issue there was fighting for a Congressional bill advocating full employment.

In case it isn’t obvious by now, A More Beautiful and Terrible History is deeply (and sadly) relevant to our current condition. Many of the same issues Theoharis decries — media inattention, liberal passivity on racial justice issues, government harassment of activists — are still in play. To that end, she concludes with a series of lessons today’s activists can take from the Montgomery bus boycott: perseverance; righteous anger; the power of simply taking action; collective organizing; disruptiveness; mindfulness about the cost of activism; having a support system and mentors; continuous education; strategizing against the inevitable blowback; and a multi-faceted plan of attack. Indeed, we’ve seen a lot of that in the thinking behind Black Lives Matter and related vanguards, as if they’d already done their homework on their forebears and vowed to go them one or several better.

For those who haven’t done that homework beyond the well-worn names and dates, A More Beautiful and Terrible History is a most useful starting point, from a contemporary perspective, for discovering how audacious — morally grounded, politically visionary, tactically ingenious, uncommonly courageous — the people of the movement actually were. They’ll come to understand why it is the worst possible disservice to the truth to imagine Martin Luther King, Jr. as anything less than a freedom fighter. It celebrates those activists in a way more significant than merely listing their achievements, by showing us how broad their thinking was, and what they and their fellow activists across the country had to battle. It’s the kind of deep historical and political analysis I wish had been around during my King Center internship, especially for those who never got to hear those stories directly from their sources.

That heated sit-down in 1978 would be my last contact with Cotton, but that meeting — and that entire summer — was transformational for me in many ways. It struck my heart, fueled my mind, and charted a moral course I’ve tried my best to follow ever since. But I’ve come to realize that the internship wasn’t an end to my movement education, but the beginning. I’m fortunate to have had at least that much, considering the lack of knowledge, willful or not, most Americans have about who (or how many) did what (and how much) to fight the power that continues to be. If Theoharis’ passionate interpretation — part supplement to the common history, part corrective to misreadings of it — taught me new things about the struggle, even after I’d spent a summer immersed in studying it and subsequent years reading and writing about that era, I imagine it would come across as revelatory, and possibly also sobering, to just about everyone else.

At the minimum, it’s propelled me to ask for Cotton’s forgiveness, as she now sits among the ancestors. I’ve grown over the years to finally understand and appreciate what she was trying to tell us. I hope she understands our youthful impetuousness back then, and I thank her for all she and so many, many unsung others did to let freedom ring.

And while I’m at it, there are many names Theoharis presents here — and probably many others as well — who also deserve gratitude. Truly, all the movements that would arise in the years after King’s murder — various waves of feminism, LGBTQ+, Native Americans, Latinx, environmental justice, Occupy and more — owe an enormous debt to the battles their foreparents fought. And all of them resonate in the tense present, fighting a backlash alternately unsure of its once-secure footing in this rootless world and mad about having that footing challenged in the first place.

That makes A More Beautiful and Terrible History an especially necessary read not only for those on the front lines of today’s movements but also for everyone who thinks the Civil Rights Movement was all about one man named King. That was what Dorothy Cotton was saying to us interns 40 years ago. I wish I’d been wise enough back then to catch what she truly meant.