Fred Rogers taught me how to speak English. As a young child growing up in a Filipino household, I spoke only Tagalog, but after watching countless hours of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on PBS, I began to gravitate toward the English language. “Won’t you be my neighbor?” he’d say, everyday, and I couldn’t help but echo the sentiment. Before long, this warm, kind-hearted man who lived on my television became one of my very first friends.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor, the new documentary by prolific filmmaker Morgan Neville, explores the profound impact Fred Rogers had on the people around him and the youth of an entire nation. Rather than take a hagiographic approach, Neville examines every facet of Rogers’ personality, ideals, and reputation — controversies and all.

Culling some of the most poignant moments from Rogers’ classic, publicly syndicated TV show as well as behind-the-scenes footage and conversations with his close friends, Won’t You Be My Neighbor reminds us of the veracity and incisiveness of his onscreen work, putting into contrast the ideals of compassion and self-love he preached with the acerbic, xenophobic sociopolitical climate of its time — and today.

Neville sat down with PopMatters prior to a screening of Won’t You Be My Neighbor at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

I’m sure you’ve spoken to a lot of people who were personally moved by the film. It was special for me because Fred Rogers taught me how to speak English. It was nice to be with him again.

So many people have this profound relationship with Fred Rogers. The thing I’ve thought a lot about is that most of us who watched the show growing up were around two- to seven-years-old. Part of that exists in our pre-consciousness. Our relationship with him predates our sense of self, our sense of identity, of labels. So, in a way, watching the film and spending time with Mister Rogers today takes you back to a part of yourself that you haven’t maybe accessed in a long time. That feels very emotional and feels really good.

Part of what I think is amazing about him as a character is that he’s trying to explain to young kids how to be people, you know? These basic humanist values of how we treat each other and how we treat ourselves and love ourselves. For him, he’s pulling it from the bible and other places, but he’s essentially saying… “love thy neighbor” is “Won’t you be my neighbor?”

These basic values are, in a way, Christian values. But to me, these are humanist values of how to behave. When he’s talking about a neighborhood, he’s talking about a community. What kind of community should we have? What kind of neighbors should we be? What kind of citizens should we be? It feels like we live in a time when a lot of us feel very out of touch with these ideas. We feel not a lot of people are putting value in civility. He’s an interesting vehicle to remind ourselves that those things matter.

When I digested down his message into one thing, “radical kindness” is what I came up with. Kindness is not sexy, and we don’t see a lot of kindness in our media or politics. It’s a lot easier to make money or rule off of divisiveness or anger or hatred. Reminding ourselves of the importance of kindness is what Fred was doing. It’s the fabric that keeps us together and looking out for each other.

When I sat down to make the film in the beginning and met with Mrs. Rogers, I said I don’t want to make a film about Fred as much as I want to make a film about Fred’s ideas. His ideas are the thing I’m responding to, not his biography. It’s the message he was trying to convey, to me, has become more important with time. I don’t care about nostalgia. The film is about the urgency of kindness.

Watching the film, I felt this strange sense of distance. I know that I probably watched every episode of the show, but I don’t remember a lot of it. I’ve changed so much, and the world has changed so much.

The world changed all around Fred. The show is incredibly consistent. He comes in every episode, changes into a sweater… you could almost do all 33 years of the show on a loop, and you wouldn’t be able to tell when what you were watching aired. He looked the same. He felt consistency was hugely important with kids. Making this film, I saw the details, and Fred was kind of maturing and tackling bigger issues.

Doing a week of shows about death for four-year-olds… nobody does that. What I think works with Mister Rogers’ voice for kids and adults is that he’s never condescending, and he’s always very direct. When bad things happen, adults tend to tell kids, “Don’t worry about it.” Kids are smart and kids know when something bad happens. Telling them not to worry about it doesn’t mean they won’t. Fred would explain the bad things to kids in ways that are appropriate. Kids are like, “Thank you for explaining to me what this bad thing is. I know that it’s bad, but nobody will tell me what it is.” I feel like that kind of direct honesty, kids responded to. Pets die. Kids can be mean to each other. We can be mean to ourselves.

Assassination.

Assassination! He did episodes that were, sometimes, overtly about things like bullying and death. But he did episodes that were allegories on nuclear holocausts and AIDS. Really heavy things.

There are some staggering clips in this film. The subject matter is heavy, and the way he explores these challenging ideas is fascinating. We’ve been in a bit of a TV renaissance for the past ten years or so, and I think Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood would fit right into the high-quality TV landscape of today. It’s like the Breaking Bad of kids’ shows. There are some clips you share in the film that are as riveting and thought-provoking as anything you’ll see on HBO or Netflix.

That’s the weird thing. I’ve been making docs for a long time, but I feel like this is the most contemporary doc I’ve made, even though it’s a film about a TV show from decades ago. In a way, I feel that not only are the issues he’s talking about timeless, but the battle he was fighting is more acute now than it’s ever been. It’s essentially trying to celebrate a world of kindness and love.

Even throughout his life, it felt like the central tension was how much of a difference he was making. He kept making these shows, and yet the world kept getting worse and worse. That trajectory hasn’t changed. But what he left behind is the message that he put into each of us who watched the show.

Hopefully, the film activates some of that and gets people talking about that. I wanted the ending of the film to not tie up everything neatly in a bow. It says, take responsibility. What is the responsibility each of us have for where we’re at today? I think that’s a question Fred would’ve asked. I think asking, “What would Fred do?” is missing the point.

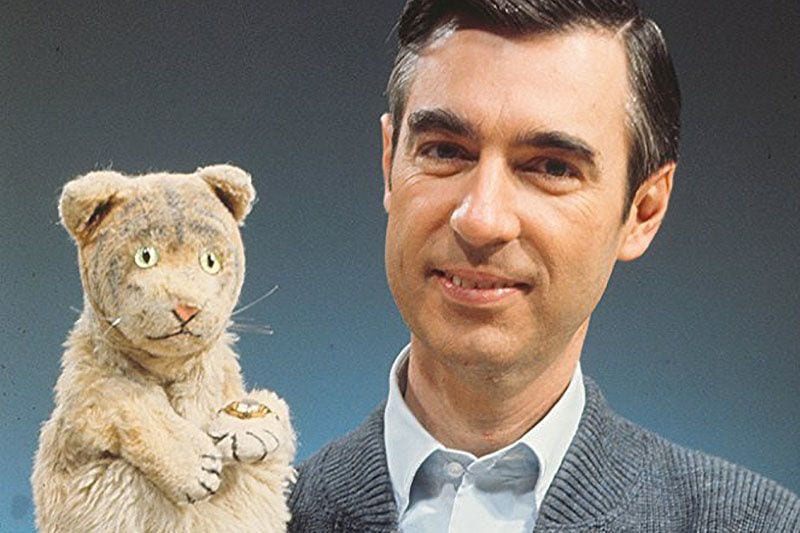

David Newell and Fred Rogers (© 2018 Focus Features) (IMDB)

I’ve always found the idea of celebrity a little bizarre. They’re these people I feel like I know on some level, but in reality, they’re essentially strangers to me. I’ve never met Fred Rogers, but I’ve cried tears for this man. I imagine that experience is intensified for a person who makes a documentary about him. You must feel like you know him intimately, in a way. And yet, I assume you’ve never met him. Is that weird for you?

It is weird. When you spend a long time making a film about someone you’ve never met, you do feel like you both know them and don’t know them. But the thing about Fred Rogers is that, I think most of us feel like there’s a gap between the public persona of a celebrity and who they really are. Making this film, a lot of people said, “Please tell me that Fred Rogers is not who I think he is. Please tell me that there’s not a huge dark side in an exposé about the ‘real’ Fred Rogers.” If anything, I feel like Fred was a deeper, more profound version of who he was on camera, which in no way contradicts who he was on camera. I think he was probably a deeper, more willful version of who he was on a kids TV show, but very much the same person. I feel like I know him because he never tried to hide himself.

The great thing about the show is that he wanted it to be a one-on-one relationship between him and the viewer. That’s why, at one point, he was getting more letters than anyone in America. And he would respond to every letter because he said, these are real relationships. A child who writes to me feels that they know me like I know them. He had an incredible capacity to be genuine, and so I feel like the Mister Rogers we felt like we all knew is genuine to who he was, which is really unique.

I talk to a lot of documentary filmmakers, and much of the time there isn’t a lot of footage of their respective subjects. They’re scrounging for footage of them drinking a cup of coffee or something.

[laughs] I’ve been in that situation.

Right! But I imagine that, with Fred Rogers, there’s just a wealth of footage. And every time he’s on camera, it’s gold. He’s saying something. There’s always a purpose behind what he’s doing on camera. As a filmmaker and storyteller, this must have been liberating.

It was amazing, I have to say. It doesn’t get better as an archive filmmaker. Not only were there the show episodes, but there were the outtakes and field pieces. The scene of him swimming was from footage they shot for a little segment in one episode, but they had all of the raw footage. There were all of the memos and scripts to every episode. It was an overwhelming amount of material that had been catalogued and were ready. It’s like they had been waiting for 15 years for somebody to come along and make a film like this. It’s never going to be better than that.

The hardest part was digesting it. I watched a lot of footage, but my editors watched a lot more. The assistant editor watched, I think, every episode. It’s 900 episodes, so that’s a lot of time.

Because you had all of this archival material, did that afford you the ability to conceptualize first and then say, we probably have footage that will support this idea?

Sometimes. On archive docs, there’s an element of it that you treat like a verité documentary. If you’ve got the footage, the footage may earn its way into the film because it’s so unique. But with this kind of material, we’re essentially making a film about a man and his ideas. A lot of times, we had many different options of how to illustrate something because he had done it so many times and in so many different ways. We tracked down a ton of commencement speeches, like 25 of them. Just going through those was great stuff. Radio interviews. The hardest part was weeding through it and cutting it down. Which is great, because archive docs live or die by the quality of their footage. This was full of riches.

Like you said, this movie is about his ideals and his ideas. Now, in real time, in the real world, you and your film are acting as a sort of megaphone for his messages. Like you said, Fred is very much alive in that he’s alive in us and his values are alive in us, the people who watched him. The film isn’t even out yet, and it’s already touched so many people.

The trailer got almost 11 million views in one day. For a documentary, that’s crazy. Part of it is, when you’re making this film, you don’t really know how much people care, how deep their relationship with him goes or how wide it goes. But seeing the appreciation and thirst to connect with that kind of voice now is kind of blowing me away. Seeing it in a theater amplifies the emotion of it. I still find it amazingly rewarding. I still get emotional. We were watching the mixback of the film and we all started crying. We made it! We’ve seen it over and over! But there’s something potent about it. It becomes something that transcends craft and storytelling. I wish I could bottle it.