Britney Spears – …Baby One More Time [Jive]

Released: 12 January 1999

We all know this album is paper-thin wank. Rolling Stone and NME railed against it when it was first released, and, even when praising it, AllMusic called it a “piece of fluff” with “its share of well-crafted filler”. But the more one researches Britney Spears‘ debut album, the more one fact becomes clear: Spears was exploited, and few of the bad things that have happened to her since were entirely her fault.

Spears tried out for The New Mickey Mouse Club at eight years old but was considered too young. She then performed as an understudy in off-Broadway shows, lost in the second round of Star Search in 1992, and returned to star on The New Mickey Mouse Club at age 11. Spears left the show a couple of years later, spent a year in high school, landed a major-label contract, and recorded her debut album in the same studio that gave us *NSYNC, Five, and Ace of Base. She was hardly allowed a real childhood, and she went through puberty under the glaring eye of the ravenous public.

Sure, Spears’ career path looks excellent on paper. Her debut shot to number one on the Billboard charts, where her subsequent three albums would also premiere. She remains one of the highest-selling female artists in history, with over 83 million units sold worldwide. And yet, much of this was achieved through the calculated, intense sexualization of the underage girl via a performer that was not legal herself. The video for the title track from Baby One More Time put Britney in a school, in the requisite uniform with her hair in pigtails, while she sings the word “baby” an astounding 22 times in three minutes. Some four months after Rolling Stone gave the debut two stars, the then 17-year-old Spears appeared on the cover in her underwear, clutching a Teletubbie to her right breast.

Sure, Tiffany had gone on mall tours in the early ’90s, but Spears’ debut marked a significant moment in the pop culture sexualization of the young girl image. The American Family Association recognized the “disturbing mix of childhood innocence and adult sexuality” and organized a boycott of any stores selling the debut. A boycott was exactly what Jive Records wanted. The Backstreet Boys were going the way of the New Kids on the Block, and they needed controversy to sell records. Who better to exploit than an underage girl with a great body, a modicum of talent, and a “For Sale by Parents” sign around her neck? Since the debut still holds the Guinness World Record in the “best-selling album by a teenage solo artist” category, the hype worked.

Spears, herself, has since paid a fantastic personal price for that record-setting controversy. Hounded continuously by up to a hundred paparazzi a day since the beginning, she got married and divorced in 55 days, randomly shaved her head in a stress-induced haze, and birthed two children who were subsequently removed from her custody for months on end. Spears was faced with the formidable task of becoming an adult while everyone in her life wanted her to stay the same. My heart goes out to her.

Of course, her debut album has not aged well. It was never expected to. It consisted of embarrassingly basic instrumentals ripped out of the Michael Jackson playbook, with her overproduced voice doing its best to give meaning to utterly trite lyrics loaded with banal innuendos. Still, none of that will ever change its place in history or take away any of its reported 25 million in sales that make it her single-most successful release. This is an album that truly launched an empire. – Alan Ranta

Bonnie “Prince” Billy – I See a Darkness [Palace]

Released on 9 January 1999

If you’ve been listening to Bonnie “Prince” Billy’s I See a Darkness on high-rotation since its original release in 1999, chances are that by now you’re well past the point of no return on some Hogarth-like Rake’s Progress, wasting away in an inevitable decline of monomaniacal introspection and intangible despair. For the slightly-rosier listener, it’s a rare treat of self-aware doom and gloom that’s best brought out from time to time and then quickly sent back whence it came.

Will Oldham, aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy, aka a bunch of other names, has always had an air of cultivated mystery about him — jumping between pseudonyms, losing himself behind bushranger beards, and drowning himself in low-fi recordings . But the real question about the highly-praised I See a Darkness is whether or not you listen to it while drinking absinthe or moonshine: it’s at once a weird Appalachian howl and cerebral arts-student debauchery. Ten years on, it remains the uneasy sticking point in this still undeniably great album.

Oldham may seem to channel the “high lonesome” sound of someone like Roscoe Holcombe or Clarence Ashley, but the flatly-stoic imagery of that old weird sound here often finds its way into slightly too-neat rhymes and clever resolutions, dredging up a hundred intangible resonances and anxieties only to then wrap them up just a little too precisely with a clever rhyme or turn of phrase.

The title track (wonderfully covered by Johnny Cash with Oldham on backing vocals the following year) paints a world of delicate and troubled existential pleas (“Many times / We’ve been out drinking / And many times / We’ve shared our thoughts” and “Well, I hope that someday, buddy / We have peace in our lives / Together or apart / Alone or with our wives”) only to try and cohere the core of it all (“Did you know how much I love you…”) into some flatly tangible psychological insight (“…Is a hope that somehow you / Can save me from this darkness”).

Similarly, a song like “Death to Everyone” is derailed into a quirkily-written but fairly straightforward statement about death’s presence in life (“Death to everyone / Is gonna come / And it makes hosing / Much more fun”).

Like most of Oldham’s work, exactly how much patience you have for the album may depend on exactly how you respond to this odd mix of intense otherworldly visions and affected statements of bohemian cleverness (before singing one of his songs in concert, Marianne Faithfull once described her friend Oldham’s desire not to be famous, bringing audible scoffs from most of the audience).

But who said that gothic visions of gloom were supposed to be subtle anyway? When you’re ready to sink into the solitary vice of melancholy, Oldham’s soundtrack still remains as perfect a complement as half a glass of absinthe mixed with half a glass of moonshine. – Kit MacFarlane

Four Tet – Dialogue [Output]

Released 1 February 1999

That Kieran Hebden’s Four Tet project could ever be charged with spearheading the insipidly-named folktronica movement is far from apparent on his debut full length Dialogue, though he does seem to be moving music forward a couple essential steps. Unlike most folk music, or electronic music of the time for that matter, Dialogue was fluid and loose, unguarded and, yes, organic. Even with such a stunning and phantasmagoric mix of freeform psychedelic noodling and rusty groove basslines, it’s hard to deny the preeminence of Hebden’s beat science on the album. It was those meticulous rhythmic cues, informed by his membership in post-rockers Fridge — though hardly expected even from those who knew that band, which made the album take on the unique shape it did. It culled free-jazz, psychedelic, raga, prog, hip-hop, fusion, indie, exotica, and beyond into a free-associative amalgamation that sounded like a family reunion wherein you could trace the genetic makeup of all those styles back to a single ancestry.

The landscape of music in the years that followed the release of the album seems to have formed in its underbelly. Even if not directly influenced by Dialogue, it’s easy to see its reflection in the woozy hard-drumming blue sunshine of Manitoba/Caribou’s “Up in Flames”, or the whimsical flutter of vintage jazz reimagined as 22nd century astral beat voyages for Madlib and the like (the late J Dilla would later remix Four Tet). Even the ecstatic tribal drumming and strange woodland/woodwind noises of tracks like “3.3 Degrees from the Pole” (built on a trance-like loop from Roxy Music’s “2HB” to add another influence to the pot) have echoes in the freakiest of folk being put out today, like Sunburned Hand of the Man, who had one album produced by Hebden. Ultimately, though, Dialogue stands as a singularity, both in Hebden’s own catalogue and in the music world in general. That it came at the end of the 20th century, typifying the abstractions of the past couple decades and signaling what was to come, is simply the icing on this delectable multi-layered cake. – Timothy Gabriele

LISTEN: Bandcamp

Pole – 2 [Matador]

Released 1 February 1999

The middle chapter of Stefan Betke’s trilogy of seminal ambient dub albums is also the shortest one, which means that it, and not 1, is the best place for novices to start. Although the three albums do differ, Pole’s sound is such that the differences are all but invisible to anyone beyond already-committed fans. Certainly the staticky pops, crackles, and bass pulses of 2 are a little more active than the almost parodically withdrawn 1, and given the lack of variation in Betke’s sound, 2‘s brief running time and unusually sprightly tracks make it the most palatable. Betke started working as Pole after he was gifted with a damaged Waldorf 4-Pole filter — Betke was interested enough in the glitchy, cracked end of dub techno that the hissing and popping the filter now produced were turned from a defect into not just a virtue, but a production aesthetic.

The nine-minute “Fahren”, which opens 2, should give any listener more than enough material to figure out whether Betke’s uncompromising style is for them. If early Pole is a dub of anything, it’s a dub of broken machinery, and it sounds like it. But there’s a reason Betke’s first three records are still lauded by the type of people who lionize Basic Channel, Deepchord, and Gas: the furiously twitching (for the genre) “Streit” and the hazy “Hafen” are pretty much as compelling as ambient dub gets, and for converts that’s very compelling indeed. Most listeners who find Betke’s work intriguing probably don’t need to go beyond this brief record, but that’s part of what makes 2 so great. – Ian Mathers

Built to Spill – Keep It Like a Secret [Warner Bros.]

Released 2 February 1999

On the family tree of Northwest rock music, Built to Spill may not be godfathers, but they are certainly the cool uncles, mixing drinks in the kitchen while the party takes place on the patio. This splendid Boise, Idaho, band spent most of the 1990s quietly drafting the blueprint for the Northwest Sound (their DNA residue is evident in the strains of Modest Mouse, Death Cab for Cutie, and other crucial Northwest bands), closing the decade with Keep It Like a Secret, ten tracks of gangly, melodic delight.

Keep It Like a Secret works at once as a firm handshake to new listeners and a warm embrace for disciples, an amalgam of the crisp, clever structures demonstrated on 1993’s There’s Nothing Wrong with Love and the gorgeous, languid sprawl of 1996’s Perfect From Now On. Meandering guitar lines wander into infectious choruses, propulsive rhythms demand sympathetic movement of appendages (tapping feet, pumping fists, air drumming, etc.), beguiling lyrics offer literate, coherent documentation of incoherent events (or perhaps vice versa) — the record secured Built to Spill’s status as demigods of the indie set, even as skeptics dismissed them as a stoner mutation of Dinosaur Jr.

Ten years later, the album still defies easy placement into a genre, sounding as vibrant today as it did on the day of its release. Perhaps the band’s fusion of muscle and melody will elicit the raising of one eyebrow instead of two from some listeners, but Keep It Like a Secret remains a stellar document from a seminal Northwest band, and a sonic pleasure in the present tense. – Bill Reagan

Of Montreal – The Gay Parade [Bar/None]

Released 16 February 1999

Before Of Montreal was one of the most discussed indie bands of the 21st century, they were merely a charming remnant of the Elephant 6 collective, working first within the Kindercore label’s oft-praised stable of psych-pop tweesters, then struggling to survive the scene’s dissolution. Years later it seems clear that the major turning point for the band came with the signing to Polyvinyl and the release of 2004’s grandiose Satanic Panic in the Attic, but way back in 1999, when more people thought Of Montreal was a description of origin than a band name, Kevin Barnes and his shifting outfit released their first truly cohesive, brilliant collection of songs.

The Gay Parade sprung out of the Athens psych-pop pack to show that Barnes and his band should no longer be relegated to the side stage behind the Apples in Stereo and Neutral Milk Hotel. Filled with lighthearted piano, bright guitars, a hodge-podge of effects, and bouncing melodies, The Gay Parade is suffused with a smiling, wide-eyed joy that those only familiar with Barnes’s recent work would find surprising. With the standard Beatles influence worn on its sleeves, the trippy light psychedelia of “Tulip Baroo”, “The March of the Gay Parade”, and “Y the Quale and Vaguely Bird Noisily” could have spilled out of any yellow submarine or lonely hearts club band, while “The Miniature Philosopher” and “A Man’s Life Flashing Before His Eyes While He and His Wife Drive Off a Cliff Into the Ocean” reveal hints of the everyday melancholy that would mark much of Of Montreal’s work in the future.

Certainly, as a band Of Montreal is constantly evolving, as is the songwriting of Kevin Barnes, but it’s informative to look back at this period in the group’s discography to reveal the path he’s charted. The Gay Parade was the first fully-formed expression of Barnes’s musical ambitions, a testament to the goddess who gave his hometown a name, and a huge leap forward from the spare twee recordings Of Montreal had yet produced. It’s the foundation for all that was to come, even as much of its innocence and lo-fi organic pop sound fell away over the years. And if a shot in the dark in 1999, The Gay Parade proved its strength by continuing the psych-pop dreams of its peers into the next century. – Patrick Schabe

XTC – Apple Venus Vol. 1 [Cooking Vinyl]

Released 17 February 1999

Opening with plucked strings and the sounds of droplets falling, XTC‘s Apple Venus, Vol. 1 makes an immediate and surprising impression. A new direction for the band is made clear at once. It’s only when Andy Partridge’s distinctive vocals come in that it becomes obvious that this is XTC, albeit an XTC making some changes.

Their first album since 1992’s much poppier Nonsuch, Apple Venus, Vol. 1 shifts to a more acoustic sound with extensive use of orchestral arrangements. Songs such as the spare “Knights in Shining Karma”, the vitriolic “Your Dictionary”, and the restrained “Harvest Festival” all offer the listener an opportunity to glimpse the musical turns XTC has taken. The band was moving forward and changing in ways that led keyboardist and lead guitarist Dave Gregory to quit a 20-year stint over creative differences during recording. Nonetheless, the band went on to create an album of sparse beauty with gorgeous melodies, biting lyrics, and allusions to 20th century classical music — a mix of the expected with the unexpected, and wholly successful in execution.

Marked by Partridge’s idiosyncratic songwriting (along with bassist Colin Moulding’s contribution of two of the more traditional XTC-sounding songs), Apple Venus, Vol. 1 fits into XTC’s previous discography while also carving out a new direction. The album is not one easily identified by its time period. In fact, ten years later it sounds as fresh as if it were just released, no easy feat for any band, much less one with such a distinct sound. Apple Venus, Vol. 1 is an ambitious album, and one that manages to exceed expectations for a band that had been releasing music for the last 20 years. – J.M. Suarez

LISTEN: Spotify

Eminem – The Slim Shady LP [Aftermath/Interscope]

Released 24 February 1999

How skilled must Eminem be that even those of us who preach tolerance and respect forgive him his misogyny? After all, this is the man who, on “My Fault”, from his first major-label release, The Slim Shady LP, mocks a girl who will suffer a fatal overdose by the song’s end, an overdose for which the song’s narrator is responsible. Among his other taunts, he says, “Susan, stop crying / I don’t hate ya’ / The world’s not against you, / I’m sorry your father raped you / So what you had your little coochie in your dad’s mouth? / That ain’t no reason to start wigging and spaz out”. Even more disturbingly, in “As the World Turns”, he fantasizes about slicing off a woman’s right nipple before he uses his “gadget dick” to “fuck that fat slut to death”. I know it sounds harsh, but, keep in mind, he kills her in couplets, so, as the kids (and Dylan) say nowadays, it’s all good.

At the time of Slim Shady‘s release, I joined the hordes of fans and critics alike who celebrated Eminem as a vital new voice in pop music. This was when Christina, Britney, the Backstreet Boys, and Limp Bizkit ruled the charts, and Em’s eventual claim that “I’m only giving you things you joke about with your friends inside your living room” wasn’t too far off. These self-serious pop stars needed to be taken down a notch. What’s more, the comeuppance should be harsh and public. Em was our guy.

His songs skewered pop culture — the Spice Girls, Pamela Anderson, O.J. — and his videos were shiny. They were excuses to play dress up, to visually take the piss out of the celebrities that he couldn’t get to in the songs. There he is as Marilyn Manson. There he is as Johnny Carson. And that patented thumb wave can only be then-President Bill Clinton. The videos were eye candy, the equivalent of getting up early for Saturday-morning cartoons for kids who now vegged out to TRL after school. The irony, of course, is that in no time at all, he was as big as those who he so openly disdained. If he was able to keep his street cred, it was only because of the muscle he had behind him: Dr. Dre.

Actually, only two songs from The Slim Shady LP credit Dre as the sole producer. Unsurprisingly, they were the two lead singles (“My Name Is” and “Guilty Conscience”, the latter on which the good Doctor also raps). Listening now, I am struck by how restrained the production is. Long stretches of “My Name Is”, for example, feature only the barest of beats and a bass line that only be described as “bored”. Elsewhere, there’s more going on — in “Role Model”, say — but, throughout, the album puts Eminem’s voice front and center, which is precisely where it should be on this, his introduction to the world.

But featuring his voice so prominently also proves to be one of the album’s many limitations, for in 1999, Slim Shady hadn’t yet discovered just how many different looks his voice had. He’s pretty much one note here — the few variances he does employ reserved for caricatures of nay-saying teachers and the like — which ultimately grates on this overly long record (more on that below). At times, the rhymes carry the day — growing up near Kansas City, I was always infinitely amused by the pairing of “naughty rotten rhymer” with “cursing at you players worse than Marty Schottenheimer” — but they are hardly redemptive. Compare any song from Slim Shady with a song like “Stan” from its far-superior follow up, The Marshall Mathers LP, and you will see just how much Eminem developed as a rapper in only a year.

The second problem with this record is that it is simply way too long. Never mind the skits — which are immediately dispensable, and an album feature that should have been done away with across the board after De La Soul’s Three Feet High and Rising — there are really only eight, maybe nine, songs here that reward a second listen. Everything else is either too stupid, too offensive, or, worst of all, too uninteresting. In this way, Eminem is just as guilty as the pop princess who records an album as a kind of single-delivery system. I don’t even know if the chaff can be called “filler”. Someone thought it was worthy, but that person was wrong. In the days of compact discs, I would have said that the “skip track” button was designed for albums like this. Today, I’ll just say that only a handful of these songs are worth importing to your iPod.

The album’s final flaw brings us back to where we started, which is to say that I once sloughed off the casual violence toward women as harmlessly amusing, and I now find it disgusting. This is the flaw that proves fatal. I don’t mean to go all Tipper Gore here, and I am fully aware that my perception is influenced by the fact that I am, obviously, 10 years older than I was when I first heard the record, and that age has brought with it what some would call stuffiness and what others would call maturity. (The last year has also seen the arrival of my first child, a son, which is a point that should not be underestimated.) Stuffy though it may be, my strongest reaction to my recent re-listen of The Slim Shady LP was that I don’t have to subject myself to such hatred.

Somehow it’s more disappointing here than it is on subsequent albums (save his most recent). Later, when Eminem more formally introduces us to his estranged wife and his pill-popping mother, the objects of his anger are at least specific. It’s less about all women and more about these two. But without that specificity, his barbs are at best juvenile, and at worst psychopathic.

Fairly or not, Slim Shady suffers in comparison to Eminem’s later work. Marshall Mathers succeeded where Shady failed in demonstrating that style can trump content when it’s inspired enough, and that Oscar for “Lose Yourself” from 8 Mile was well deserved. The Eminem Show had its moments, but, for the most part, Eminem has been treading familiar ground for the past eight years (when he’s been treading at all). His new album — the appropriately titled Relapse — is all but unlistenable (or so I thought, until he rhymed “pneumonia” with “bologna”), which further casts Slim Shady in doubt as we wonder if he was ever that good to begin with.

The answer is that, yeah, he was good. Just nowhere near as good as you remember. – Kirby Fields

Sleater Kinney – The Hot Rock [Kill Rock Stars]

Released 23 February 1999

With all the critical attention heaped on Sleater Kinney after the release of the anthemic Dig Me Out, it seemed that the band had successfully resuscitated the waning riot grrl movement and would become its strident standard bearer into the new decade. But The Hot Rock effectively put an end to that idea. The opening track, “Start Together”, suggests that this was no accident: “Everything’s changing”, Corin Tucker sings. “Not the one you wanted”, the title track’s refrain runs, “not the thing you keep”.

It’s as though Sleater Kinney wanted to be sure they wouldn’t be graded on a curve by fans who were just grateful to see women rocking out. The album offers no shout-along choruses. Instead, it features overlapping vocals that alternately intertwine and cancel each other out. Propulsive riffs are replaced by subdued, sinewy guitar lines that occasionally wind themselves into intractable knots. The songs eschew the more overt feminist themes explored on previous albums and focus more on relationship entropy, with lyrics revolving around nautical metaphors of sinking ships and failed captains.

The seductiveness of difficulty for its own sake and for surrender seems to hang over the record, particularly the single “Get Up”, which opens with this spoken-word exhortation: “And when the body finally starts to let go / Let it all go at once / Not piece by piece”. With The Hot Rock, the band seemingly flirted with the idea of letting it all go, devolving their established approach to retreat from success and spin intricate and insular odes in obscurity. But then a few years later, they were on tour with Pearl Jam. – Rob Horning

The Roots – Things Fall Apart [Geffen/MCA]

Released 23 February 1999

If the Roots are the best hip-hop band of all time, then Things Fall Apart is their greatest record. This isn’t a collection of singles, but a statement about the evolution of hip-hop as an artistic movement. The challenge was simple: could hip-hop artists produce an actual album and not just a collection of singles? This is suggested as well on the first track, “Act Won (Things Fall Apart)” — “Hip-hop records are treated as though they are disposable. They’re not maximized as product even … [or] as art”.

Although it was considered brilliant when it was released, there is no doubt that the importance of this record has only grown over time. Now it is essential, a classic, a gold standard by which all other hip-hop records before and since should be measured. It is the single most influential hip-hop record since Eric B. and Rakim’s 1987 debut, Paid in Full (a fair comparison since the Roots’ MC, Black Thought, is the best rhymesmith since Rakim).

If hip-hop had become weak and ostentatious by 1999, then 10 years later, much of the genre has become a mockery of itself. Things Fall Apart is a concept album about what it means to be in hip-hop and what the music can do for the soul if done properly, if done with TLC by a group of musicians who understand hip-hop’s history in such a way that it can be channeled for future generations.

There is not a single weak track on this record, and it can — and should — be played continuously. There are some standout tracks, though, the best being “The Next Movement”, “Double Trouble” (with a killer rap duet featuring Mos Def), and “Act Too: Love of My Life”, the only love song I’ve heard written for hip-hop as a whole. Says Black Thought, “Sometimes I wouldn’t-a made it if it wasn’t for you / Hip-Hop, you the love of my life and that’s true”.

Most people are drawn to the album’s biggest single, “You Got Me”, which features guest spots from Erykah Badu and Eve, and was originally written by Jill Scott. It is an astonishing and timelessly beautiful song with a kind of openly romantic honesty that is absent in hip-hop today. Drummer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson may be one of the best drummers in the world, period, and the producers allow Thompson to sample himself by ending the track with a drum-and-bass-inspired backbeat staccato.

But, “You Got Me” is just one of 18 solid tracks that all seamlessly blend into each other with an album production reminiscent of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Things Fall Apart is a massive collaboration of talent — Black Thought, Questlove, Kamal Gray’s keyboards, Leonard Hubbard’s bass, second MC Malik B’s skills, and a host of guest musicians and artists (DJ Jazzy Jeff, Common, D’Angelo, Beanie Segal, Scott Storch, Mos Def, etc.).

Listening to hip-hop now, it is shameful to see just how extra-terrestrial the music has become (and not in a cool, Parliament Funkadelic kind of way). But if we educated our youth on the true meaning of hip-hop and its roots — socially-relevant lyrics, jazz, blues, and rock and roll — then we, as a people, would be in a much better position to vocalize our thoughts and our emotions through positive music. The Roots’ Things Fall Apart is a quintessential record in the fight against ignorance because it challenges the hip-hop community to expect more of itself and hold the community accountable. – Shyam Sriram

Prince Paul – A Prince Among Thieves [Tommy Boy]

Released 23 February 1999

It’s safe to say there hasn’t been a concept album in the hip-hop world nearly as effective and self-realized as Prince Paul‘s A Prince Among Thieves before or since its conception. Over the ten years since the album’s release, there have been other valiant efforts at hip-hop concept albums — namely Kanye West’s 808s and Heartbreak, MF Grimm’s American Hunger, and MF Doom’s Mmm Food. But the thing they’re all missing is the actual substance and imagination that Prince Paul mustered up. The aforementioned albums deal with either realistic issues directly or obscure, bizarre references (I’m talking to you, Doom), while A Prince Among Thieves thrives in the simple nature of storytelling. And where Paul’s earlier production on De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising was highly conceptual, it didn’t have the cohesive storytelling and imaginative premise that his own pet-project did.

A Prince Among Thieves is an entire world created by Prince Paul, and he has complete control over the story, the characters, the beats, and the overall experience. There are a number of things that made the album significant. Most importantly, he recruited some of the era’s best emcees to fill the roles he had planned out. Tariq, the main character that strives for a record deal, is played by the highly underrated and relatively unknown Juggaknots’ Breeze, with additional appearances by Big Daddy Kane as a pimp, Sadat X and Xzibit as inmates, and the best part of all — Chris Rock and De La Soul as the neighborhood crackheads.

Not only was A Prince Among Thieves a testament to the talent of Paul, but also to that of the late ’90s alternative hip-hop world. This was a culmination of all his best work rolled into one, and its meticulous planning and inimitable delivery leave it as one of the landmark albums in hip-hop history. – John Bohannon

TLC – FanMail [LaFace]

Released 23 February 1999

Surprisingly scoring one of the decade’s best R&B albums with 1994’s CrazySexyCool, TLC took a long five-year vacation (precipitated by everything from group member T-Boz’s sickle cell anemia to the band’s bankruptcy) before returning with the decidedly mediocre FanMail. Barely featuring group sparkplug Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes (sadly, it would be the last album the group released while she was alive), Fanmail is largely missing the sass and the sense of fun that carried this merely moderately talented group through two successful albums.

This multi-producer hodgepodge features a well-past-their-primes Dallas Austin and Babyface (with no Puff Daddy and only a cameo from Jermaine Dupri), and goes heavy on the goopy balladry, with ghastly adult contemporary slow jams like “Dear Lie” and “I Miss You So Much”. In retrospect, you could have waited for TLC’s greatest hits compilation to catch this album’s good moments: the playground singalong “No Scrubs”, the electro-hop “Silly Ho”, and the surprisingly effective rock ballad “Unpretty”.

FanMail went on to sell a kazillion copies and win a handful of Grammy Awards, so I may be in the minority here, but the amount of copies that line the bins of used record shops these days is probably the most telling fact about this album. One would have hoped that a half-decade would’ve provided enough time to buy much better material. – Mike Heyliger

Underworld – Beaucoup Fish [V2]

Released 1 March 1999

In 1999, techno/rave/electronica/dance music/whatever you want to call it was exploding. Even if 1997’s predicted transformation into an e-shaped, glowstick-twirling, PLUR-rific globe didn’t exactly materialize, filmmakers, journalists, cultural theorists, and aging musicians were still, two years later, struggling to figure out what the hell this music was, what it represented, where the hell it came from, and what the hell it wanted from us.

Underworld, a band nearly two decades old by 1999, had already fully embraced the style, and became a major player with their massive club anthem “Born Slippy .NUXX”, known to most Americans as “that song from Trainspotting“. Expectations for the new album were insanely high. Purists wanted something without a hint of sell-out or crossover to keep the scene from being gentrified. Newbie party-crashers wanted “Born Slippy parts II-XII”, ecstatic rave-ups translatable to rock and hip-hop audiences.

Beaucoup Fish was instead a wide plate that seemed neither too unapproachably Underworld — particularly since only one track on the album didn’t have vocals (“Kittens”) — nor lacking in Underworld’s signature trance riffs, tribal drum exercises, or pummeling club sensibility. Far from a compromise though, Beaucoup Fish is a diverse and mature outing by a band comfortable enough in their own skin to expand their depths, be it through melancholy vocoder elegies (“Winjer”), ambient space croons with no beats (“Skym”), braindead-simple hip-hop with gigantic beats (“Bruce Lee”), or arresting and sublime synthpop that outshines the entirety of the band’s catalogue back when they used to solely do synthpop (“Jumbo”).

Karl Hyde’s stream of consciousness verse provided absurdist propulsion for the album with his slam-style reading of “Push Upstairs” being perhaps the first and last slam-style reading to ever work on record post-Soul Coughing. Perhaps the most recondite is all the babbling about ding-dongs and Tom and Jerry in the album’s most massive track, “Shudder/King of Snakes”, which interpolates arpeggios off of the pivotal Summer/Moroder anthem “I Feel Love”.

The diversity of the album is likely what has kept the album fresh, as a recent spin confirmed in this reviewer that it hasn’t aged an inch. After this album, Darren Emerson departed and the band soon fell from great heights as the Ritalin flirtation with techno came to a close. – Timothy Gabriele

Godspeed You! Black Emperor – Slow Riot for New Zerø Kanada [Constellation]

Released 8 March 1999

On the front cover of Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s sole EP sits a Hebrew phrase from the Book of Jeremiah: tohu va-vohu — in English, “void” or “nothingness.” It comes from the verse in which the Lord goes medieval on the Earth and turns it into a barren wasteland, which is printed in the liners along with a scribbled call to action: “Let’s build quiet armies, friends.” On the reverse side is an Italian pictorial diagram of a homemade bomb. Nothing out of the ordinary for this shadowy Canadian collective, who, from their first proper album (F#A#(infinity)) in 1997 until their indefinite hiatus in 2003, possessed the dumbfounding ability to make all this fire-and-brimstone mishegaas seem as serious as a heart attack. An apocalyptic black mystique still surrounds Slow Riot for New Zerø Kanada; ten years, the disclosure of the players’ identities, and a glut of post-rock copycats have done nothing to diminish its power.

Although it’s only two tracks and runs a bit under half an hour, Slow Riot is an EP in name only, given the reputation of EPs as precursors or B-side fat. In Godspeed’s case, it was simply another way to release the monolithic music they explored on F#A#(infinity) in twice the time. Conciseness is a virtue, as many an educator has told us, and here the band made impressive use of an economical format, cultivating the songs to maturity without wasting an iota of space. At the same time, they were beginning to move away from the post-apocalyptic drift of their debut and toward tightly wound passages of tension and release.

On “Moya”, the first track, strings caterwaul for several minutes before the floor drops out and a lone guitar weeps for them in near-silence. The band then flips the elegiac scene right on its head as the instruments pick themselves up and fuse together, climbing like espaliers and collecting enough strength for a hard-won climax. Not casual listening by any standard, but the song’s objectively high quality managed to keep swaths of diverse audiences mesmerized over its daunting length.

The band’s improved compositional skills extended to their field recordings, which were both more effective in themselves and more effectively placed into the overall context. Only Mogwai and a scarce few others ever came close. Slow Riot is especially significant for featuring what is arguably (and boy, have we argued) the best track in Godspeed’s oeuvre: “Blaise Bailey Finnegan III”, a synthesis of orchestral sturm und drang and man-on-the-street diatribes that would make any sound artist envious. The group found the titular derelict on a sidewalk in Providence, RI, and taped him spewing scarily focused vitriol at the country that abandoned him. When he lists off his weapons one by one, it’s hard to tell whether he’s merely nuts or extremely dangerous, just as we’re forced to question if music by itself can’t contain actual violence.

But Godspeed deal in destructiveness of a very particular kind. The verse in Jeremiah concludes with the Lord assuring, “Yet I will not make a full end.” With its multitude of languages and conflicting messages of religiosity and anarchy, Slow Riot for New Zerø Kanada was the place where Godspeed You! Black Emperor looked a bit like gods themselves, pissed off at a fucked-up world they’d be willing to destroy if it would bring about a new beginning. – M. Newmark

LISTEN: Bandcamp

Silverchair – Neon Ballroom [Sony]

Released 8 March 1999

Regarded by Daniel Johns as Silverchair’s “first record”, Neon Ballroom was indeed an evolution from the adolescent grunge days of Frogstomp and Freak Show. The members of the band were only 18 when they composed Neon Ballroom, but the band always proved more mature than their age. Immediately, opener “Emotion Sickness” showed a whole new side to the band’s ability to compose. Adding strings, piano, and a new, more evolved level of song structure, “Emotion Sickness” remains a fan favorite, often regarded as one of the band’s best songs ever written.

Even the generic rocker “Anthem for the Year 2000” proved the band’s ability to evolve with the times. As grunge died, they moved on, becoming a more versatile act than grunge giants Pearl Jam or Soundgarden. Throughout the album, electronic flourishes grace the album to further the band’s experimentation into poppier territory. Of course, these influences would come to dominate their later albums Diorama and Young Modern.

Johns also grew as a lyricist, evolving out of the pure angst he demonstrated on the band’s first two albums. “Ana’s Song (Open Fire)”, of course, dealt with his struggle with anorexia, a condition that would set the band on hiatus in later years. It’s already an elevated topic, but the way he develops the topic is quite original: slurring his words “Ana wrecks your life” to sound more like “anorexia.” Neon Ballroom may have been more of a stepping stone to Diorama than anything, but it was surely Silverchair’s coming out party in terms of musicality. – Tyler Fisher

Stereophonics – Performance & Cocktails [V2]

Released 8 March 1999

Following the passionate and invigorating pub-rock of Word Gets Around, Performance and Cocktails couldn’t help but sound jaded and disappointed in comparison. Though the Welsh band’s 1997 debut hardly viewed the vagaries of small-town life through rose-colored glasses, it presumed a deep deposit of proletarian sincerity beneath the stratum of alcoholism, sex, and social dysfunction. Performance and Cocktails, however, follows frontman/lyricist Kelly Jones as he tours the world and finds it wanting.

The album is a balanced, bewildered take on hypocrisy and inauthenticity, from the country-club culture evoked by the title on down to the glazed stare of the woman being kissed on the cover (the model later revealed that an absinthe-and-opium hangover contributed to her iconic mask of detachment). Jones’ blunt truisms may not have the sophistication of Thom Yorke’s alienated Orwellian enigmas, but they display a sturdy poetry all their own. He sniffs at plastic Californias, incredulous wireless radios, head-standing lotharios with bad tans, and those who “rely on a lie that’s true”. The album’s best moments claw fitfully at the deeper anxieties beneath the Formica patina of postmodern culture: capitalist wish-fulfillment (“Just Looking”), bureaucratic diffidence (“Hurry Up and Wait”), free-wheeling exploitation (“The Bartender and the Thief”), and, of course, aging and death (“She Takes Her Clothes Off”).

Jones saves his neatest trick for last, suggesting in the wily and smoky closer “I Stopped to Fill My Car Up” that storytelling is itself the greatest lie one can tell. The world-weary doubt that serves Stereophonics so well here would congeal into bored cynicism on their weaker later releases, but on Performance and Cocktails it remains a blunt instrument of considerable might. – Ross Langager

Beulah – When Your Heartstrings Break [Sugar Free]

Released 9 March 1999

Has anyone in indie rock sported a bigger heart on his sleeve in the past ten years than Beulah frontman Miles Kurosky? The San Francisco-based pop collective called it a day back in 2004, citing intraband strife and the dreaded growing up and growing older, but it’s small wonder that Kurosky didn’t die of a broken heart on 1999’s masterpiece, When Your Heartstrings Break — an album fixated on love and all its twists and turns, drenched in horns, strings and keyboards until it’s overflowing with (sigh) everything.

Don’t let the refrigerator magnet poetry song titles (“Emma Blowgun’s Last Stand”, “Comrade’s Twenty Sixth”) and full-to-bursting production fool you; with eleven songs in 34 minutes, opening with the joyous horns and “ahhhh”s of “Score from Augusta” and capped by the says-it-all closer “If We Can Land a Man on the Moon, Surely I Can Win Your Heart”, Heartstrings perfectly captures the pulse-quickening highs and head-in-hands lows that accompany being a 20-something in love.

Ten years out, though, what’s the lesson? First, to thine own self be true: Beulah felt in, if not necessarily of, the Elephant 6 collective, opting for cynical directness where their peers went obtuse. Second, growing up — and pinpointing that moment, uh, when your heartstrings break — can be a bitch, but your spirits can always be lifted by a trumpet section. – Stephen Haag

Wilco – Summerteeth [Reprise]

Released 9 March 1999

Even if I pretend to know nothing about the circumstances behind the recording of Wilco‘s Summerteeth (because I think records should stand on their own), it still comes across as one of the loneliest and most despairing records of its time. And the fact that Summerteeth is an alt-country album rather than a raging slab of dysfunctional deathcore makes the despair that much more palpable.

Look at the band members, posing individually in desolate settings in the CD booklet: under unforgiving fluorescent lights in an institutional hallway; by a self-service gas pump late at night; in a bleak wood-paneled room furnished by two plain chairs and an unused megaphone. (The band member in the room with the megaphone, hands in his pockets and eyes focused on nothing, is the talented multi-instrumentalist Jay Bennett, who passed away on May 24 of this year.)

And consider the lyrics: “The shadow grows / His heart’s in a bowl behind the bank / And every evening when he gets home / To make his supper and eat it alone / His black shirt cries / While his shoes grow cold.”

Or “The ashtray says / You were up all night / When you went to bed / With your darkest mind / Your pillow wept / And covered your eyes / You finally slept / While the sun caught fire.”

Or, simply, in a Dylanesque song called “She’s a Jar”: “She begged me not to hit her.”

The pop side of Wilco prevents the loneliness from becoming lugubrious, and songs such as “Can’t Stand It” (a should-have-been-hit-single) and the moodily beautiful string arrangement in “She’s a Jar” speak to Wilco’s — and Jeff Tweedy’s — ability to get outside of their own heads and connect with discerning listeners. A relative disappointment in terms of sales, Summerteeth deserves another listen ten years down the road. – Michael Antman

Blur – 13 [EMI/Virgin]

Released 15 March 1999

With 13 — a sprawling, noisy, meandering mess of a would-be masterpiece — Blur completed their break from the classicist Britpop that had been their bread and butter since 1993, a transition that began on 1997’s self-titled album and finds its consummation here, on their most adventurous, interesting, and flawed album.

Though on its surface it sounds like it might be a bold, but clumsy, attempt at rebirth, a possible new beginning, 13 is actually mostly concerned with endings: the end of the band’s longtime relationship with legendary producer Stephen Street (who was instrumental in shaping the sound of another little British group by the name of the Smiths) in favor of knob twiddler William Orbit; the end of their former pop formalism and lyrical wit in favor of a more fluid, almost formless aesthetic; the end of Albarn’s long-term romantic relationship with Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann (which break-up fueled a good portion of the album’s lyrical content and its overall tone); the beginning of the end of the core songwriting relationship in the band between singer Damon Albarn and guitarist Graham Coxon (though the latter wouldn’t actually leave the band formally until the next album, Think Tank); and, I suppose, the end of the millennium (or the “End of a Century”… ha!).

A classic case of ambition far outstripping actual reach (and being all the better for it), 13 is less of a reinvention than an attempt to completely dissolve the band’s old crisp concision and pop eclecticism in a… ahem… blurry sonic soup of squalling distortion, electronic flourishes, buzzsaw guitars, jammed out noodling, extraneous instrumental interstitials, indulgent song lengths, and nonsense lyrics. There are a few recognizable parts of the old Blur buried in there somewhere, but the band seems fully intent on sloughing off its old self — damn the fans, damn sales, damn Britpop.

The kitchen sink approach taken to both the songwriting and overall production and sound yields a wildly uneven, but always captivating, album that is relentless in its desire both to discourage and surprise in equal measure. The latter applies to the stunning album opener, and lead single (at nearly eight minutes!), “Tender”, a towering, shambling, sad sack break-up song buoyed up and thrown heavenward by a gospel-tinged choir. Its slow, swelling, almost tribal build-up on a simple repetitive guitar line and vocal melody, coursing from emotional frailty up through to exultation, is the frontloaded highpoint of the album, and possibly of Blur’s entire career.

13 veers off sharply thereafter — perhaps by accident, perhaps by design — crashing down into the howling paranoid glam rave-up “Bugman”, followed by the only really recognizable old school Blur song, “Coffee and TV”, before wandering off and losing its way in a number of muddled, confounding songs in its middle section. These seem often more like the germs of songs than songs proper, experiments that are picked up and then abandoned before completion and paring down (most of them stretch out needlessly past five minutes, and a few past seven).

13 redeems itself on its back third, though, before adjourning with the bookend and answer to “Tender”, the beautiful, wistful ballad “No Distance Left to Run” — a tired dirge that caves in to resignation and acceptance in the face of the inevitable end of things. The end of love, of the millennium, of the old Blur. – Jake Meaney

Tom Russell – The Man from God Knows Where [Hightone]

Released 16 March 1999

To suggest that Tom Russell’s album The Man from God Knows Where should feature on American History syllabuses may not sound like the ultimate compliment. But part of the brilliance of this undervalued multi-vocal song-cycle — or “folk opera” — is to illuminate American immigrant experience in a complex, ambitious-but-accessible, vivid, and thoroughly enjoyable way.

Drawing deeply on his own background as the child of Norwegian and Irish immigrants, Russell produces a record that is at once utterly personal and totally expansive, charting the experiences of a variety of characters in a manner both intimate and mythic. Subtle and tasteful arrangements built around Old and New World musical traditions and augmented with snatches of hymns and folk songs provide the rich musical context. Vocally, Russell enlists the help of a stellar line-up of roots music luminaries, placing his own burly, authoritative, Johnny Cash-ish tones alongside Dolores Keane’s smouldering soul-of-Ireland burr, Iris DeMent’s aching high lonesome twang, the austere Scandinavian sounds of Kari Bremnes and Sondre Bratland, and the off-kilter croak of Dave Van Ronk. Even Walt Whitman gets in on the act, with Russell brilliantly incorporating a bit of the poet’s voice as recorded by Thomas Edison on wax cylinder in 1890.

The cast sensitively inhabit characters ranging from Sitting Bull to a lonely prairie housewife, and the album broadens out into a dazzling array of narratives and perspectives, unfolding like an epic motion-picture as its characters confront homesickness, prejudice, joy, and disillusionment in their new land. Russell’s potent investigation of American realities and mythologies makes The Man from God Knows Where an album not simply for 1999, or for 2009, but one for the ages. – Alexander Ramon

[ Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 ]

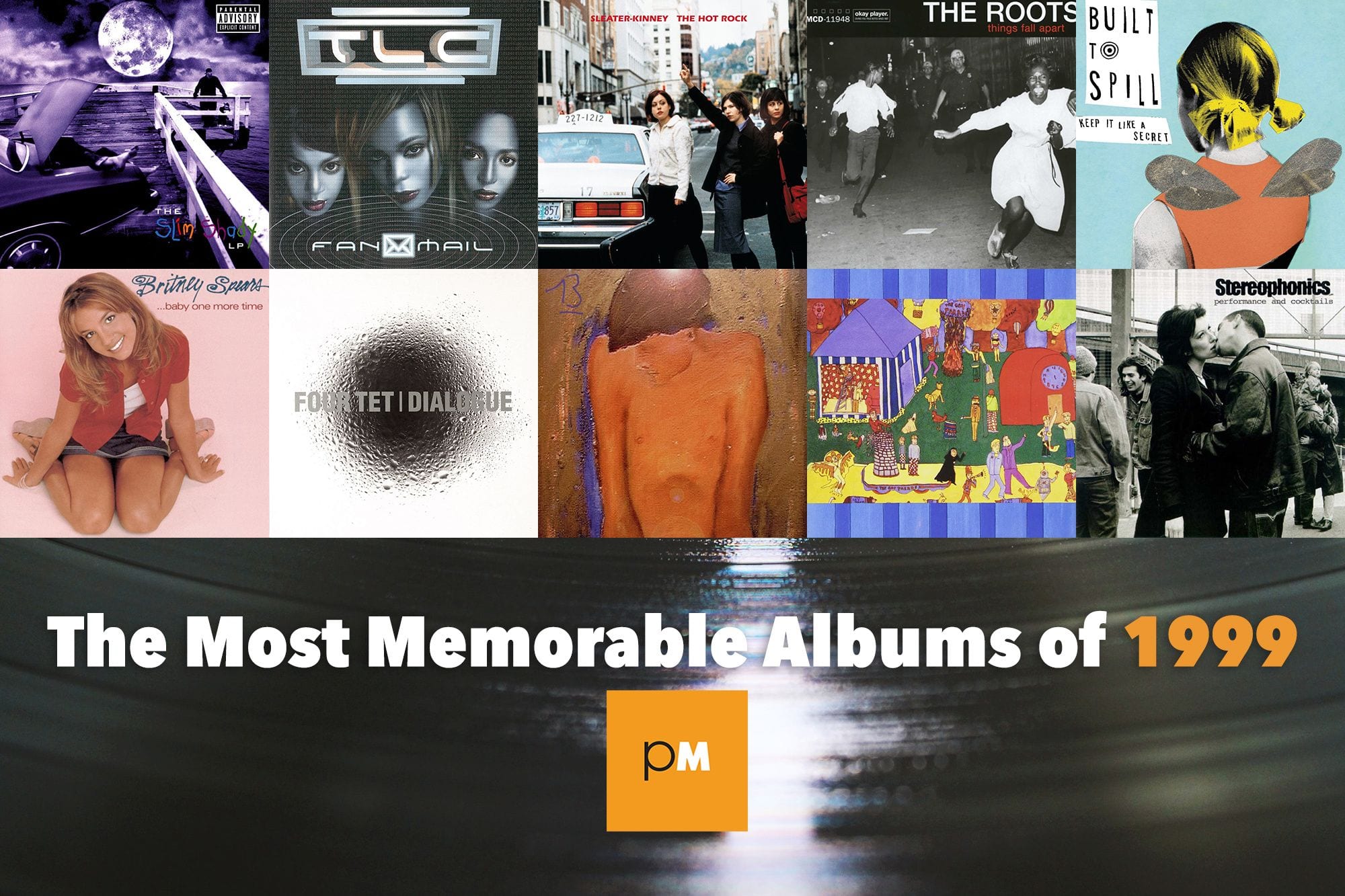

In the relative safety of comfortable hindsight, think back to that moment of propulsion as our collective species hurtled towards one of time’s inevitable barriers. One of the most expansive and reflexive centuries in history was slamming to a close, and an equally mythologized future was careening toward us, promise, and uncertainty reaching out to pull us forward. And that moment even came with its pop soundtrack — appropriately-ironically-enough written 17 years earlier — as we danced the

fin de siècle shuffle, partying because it was, at last, 1999.

That culturally impregnated year saw the birth of

PopMatters, finding its nascent voice as an open-ended exploration of the cultural moment, and continuing in this vein for the first two decades of the chrome-bright 21st century. From the start, PopMatters loved music — loved what music means in art, history, culture, and society; loved what music means to people — and it’s only natural that we care about the music of the year we were born.

But the music of 1999 has more importance than a mere catalog history of chart positions and popular tunes suitable for cutesy birthday cards. As mildly embarrassing and forgettable as “Y2K” paranoia seems now, it’s easy to forget that music was experiencing the same cultural moment like every other human endeavor: a preparation for passage. Nothing marks the interconnectedness of the human race quite like the triumph of the Gregorian calendar, and the looming turn of a new century was a planetary phenomenon. Even the hazy confusion over the actual beginnings and endings of centuries is an attendant example of how this preparation for passage was marked with uncertainty and anxiety, and no small amount of anticipation.

Any number of genres scrabbled through the 1990s to be the ascendant king of the final days or first voice of the future. For a time, it seemed obvious that electronic dancescapes would be the champion of a brave new world. But hip-hop had already begun to assimilate the planet, and even traditional forms like Americana and country found new revivals. Jazz, punk, metal, Latin, world, indie, and pop — the entire 20th century seems to be represented in 1999’s plethora of releases. One peek at the exhaustive list of

1999 albums on Wikipedia reveals just how diverse human song was as we sung out the old cycle.

In sorting through the list of 1999 releases to select some of the most noteworthy, PopMatters sought out those releases that marked out 1999 in their distinct ways. Whether or not you consider the success of Britney Spears and Blink 182 to be worthy or a stain, their impact on how we listened in 1999 is inescapable. Mainstream country gained massive crossover appeal in the Dixie Chicks’ sophomore effort and lost the same as it lost Garth Brooks to Chris Gaines. Whether the idyllic icon of the West Coast was won by the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Rage Against the Machine is still debated. Eve, Missy Elliot, TLC, and Macy Gray offered competing pop narratives for women, while the war of cool on the dancefloor was waged between Air and Basement Jaxx while old-timers the Underworld slipped in the back door.

Some of the artists herein made grand final statements in 1999 (XTC, Ben Folds Five), while others debuted to a mere glimmer of the success they’d achieve in the new century (the White Stripes, Eminem). Most are names that continue to influence and shape the discourse of popular music in 2009. And whether or not the artists remain vital in the present, these are the albums that shaped 1999, that expressed the electric trepidation and expectation on the edge of change, and helped to shape the future. –

Patrick Schabe

This article was originally published on 21 June 2009.