Reprinted with permission from Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power by Aaron Cohen (footnotes omitted), published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2019 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chapter 1

Hallways and Airwaves: Changing Neighborhoods and Emerging Media Inspire New Music

Sometime in early 1958, five singers and their manager navigated a stretch of Chicago’s South Michigan Avenue known as Record Row. Confident, persistent, and with nothing to lose, they hoped that one of the equally undaunted companies lining the street would change their fortunes. Had they traveled the entire mile and a half of the street, they would have ambled from Roosevelt Road on the north to East Twenty-Fifth Street on the south. Collectively known as the Impressions, these vocalists, in their late teens and early twenties, were from the Cabrini-Green public housing project on the North Side. Curtis Mayfield was not yet sixteen. Decades later, he recalled snow up to their necks that Saturday morning. But it proved little hindrance as he carried his guitar and amplifier down the street. Eddie Thomas, the group’s manager, came from the South Side. He was about ten years older, and his education in the music business combined street smarts with improvisation. They recalled that their first stop was a company called King, but its roster was full. Then they called on Chess Records—same response. Next they approached a record company named Vee-Jay on the other side of the street.

“We went over there, and I introduced myself to Calvin Carter, who was the A&R director at the time,” Thomas recalled. “I told him I’d like to bring my group over. So we set up a date to bring them in. And we went back over to Vee-Jay Records; a cold winter night too. Snow on the ground. And we did a couple songs and he said, ‘Man, your group is sounding good.’ And I said to Curtis, ‘Go and do “For Your Precious Love.”‘ We did one take. Where’s the contract? OK, they signed us up.”

As Jerry Butler remembered it, their interests were to be heard and not to be cheated. Almost fifty years later he recalled, “We just wanted to see if someone would listen to our songs without a [hidden] tape recorder going in the drawer.”

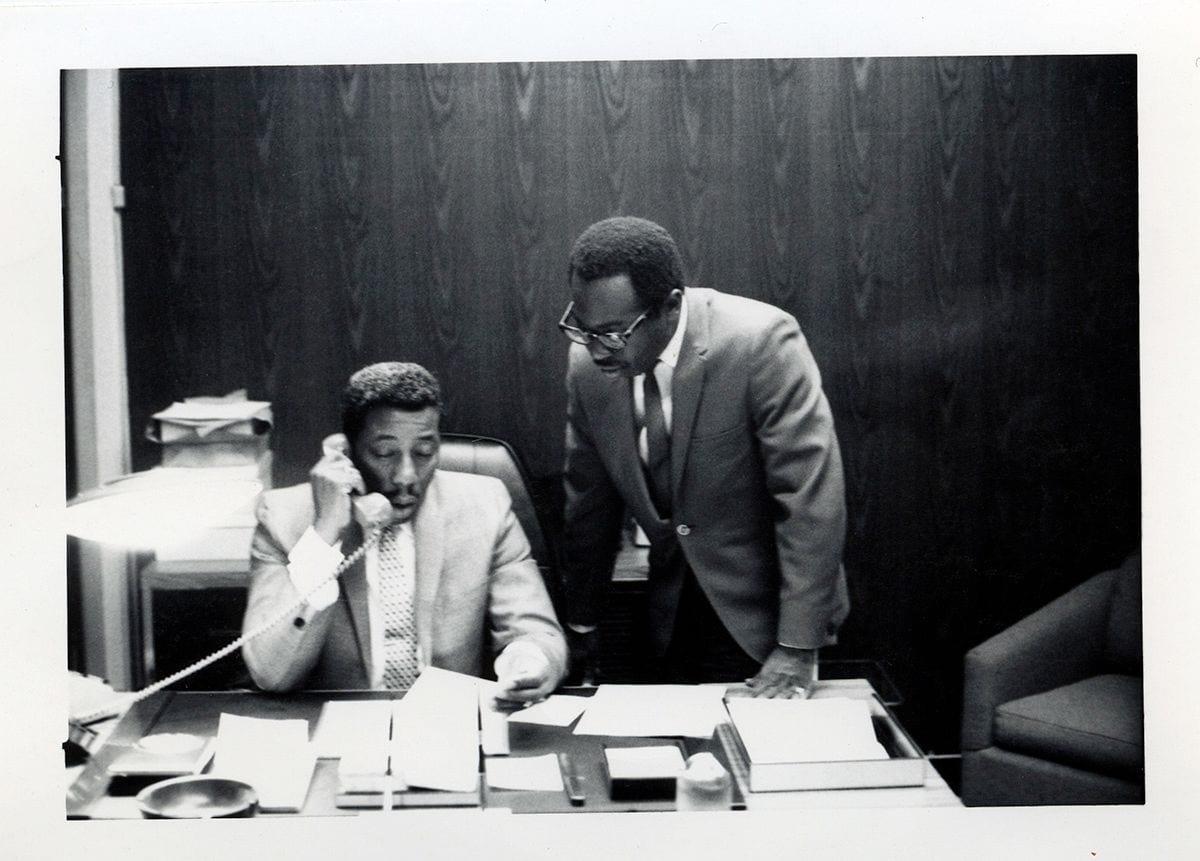

Eddie Thomas (left) and Curtis Mayfield. Courtesy of Eddie Thomas. (University of Chicago Press)

This sequence of events and its aftermath—a hit song, international fame for the group, and solo careers for Butler and Mayfield—plays out like the kind of life-defining moment confirmed through collective memories. Legends do tend to conflict with other published narratives, but several singers, instrumentalists, and producers who grew up in Chicago at that time experienced similar moments. Some of these artists and producers worked on or near Record Row, others worked throughout the city. Many of them lived through the circumstances that led to the recording of such songs as the Impressions’ “For Your Precious Love.” Major social shifts ran underneath that tune’s four chords, Mayfield’s lyrical guitar lead, and the group’s incantatory harmonies.

Those harmonies convey understated power. No big vocal leaps or instrumental flourishes were needed to make “For Your Precious Love” a departure from the doo-wop that came before it. While only a few people were on hand for the recording, a community generated the circumstances for this song to be created—and for a larger audience to hear it. Not only had the Great Migration from the South dramatically boosted the black population of this midwestern city, but the Impressions’ generation forged an identity through music. Diverse circumstances strengthened Chicago-area teen culture during the 1950s and 1960s. Songs frequently arose within the hallways of public housing projects or schools, places full of teens with plenty of ideas, and varying religious denominations informed young singers’ vocal training and inflections. The process of recording “For Your Precious Love” also reflected bigger changes. This single was cut for an African American–owned company, Vee-Jay, that was a landmark operation but not the only one of its kind. Emerging radio personalities provided airtime for records like these and spoke the same dialect as their listeners. These media voices would promote new economic resources and political advances as eagerly as they broadcast R&B hits. The real financial beneficiaries of these developments would always be questioned—these were commercial enterprises, not social missions. But whether or not everyone acted in harmony, and even if a burgeoning movement did not yet have a name, this record announced a push forward.

On the eve of the civil rights movement in the 1950s, many Chicagoans had a great deal to push against. Schools in African American communities faced overcrowding and other entrenched difficulties. Barriers to equal employment were visible throughout the city; Butler remembers walking downtown and seeing signs that barred blacks from applying even for dishwashing jobs. His memoir describes the racism he encountered as a student at Washburne Technical High School, a vocational institution near Cabrini-Green. He knew that the program could take him only so far, since white-dominated unions ran apprentice programs specifically to keep blacks out of skilled trades. Butler, like other black musicians from his generation, remained steadfast.

Black musicians who came of age in Chicago from the 1950s through the 1970s usually were either part of or not far removed from the mass movement of hundreds of thousands of African Americans who left the South for the Midwest’s largest city. As journalist Isabel Wilkerson noted in The Warmth of Other Suns, the Illinois Central Railroad “carried so many southern blacks north that Chicago would go from 1.8 percent black at the start of the twentieth century to one-third black by the time the flow of people finally began to slow in 1970.” By the 1950s, moreover, these new Chicagoans would “arrive with higher levels of education than earlier waves of migrants and thus greater employment potential than both the blacks they left behind and the blacks they joined.” They also tended to have more education than the city’s white immigrant arrivals. Parents sought to pass this advantage on to their offspring, although they faced institutional barriers within a school system that was 90 percent segregated by 1957 (and remained so sixty years later, when the city’s public school students were 47 percent Latino, 37 percent African American, and 10 percent white). As the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) reported, “In cost and quality of instruction, school time, districting and choice of sites, the Chicago Board of Education maintains in practice what amounts to a racially discriminatory policy.”

The fight against discrimination became as internal as it was organizational. Leon Forrest, who grew up on the South Side in the 1940s and 1950s, argued that his family and neighbors took on structural disadvantages through survival strategies and mutual support systems. In his essay collection Relocations of the Spirit he wrote, “More than anything else we believed that the individual had to find something within himself, some talent, moxie, intelligence, magical nerve, swiftly developed skill, education, knack, trade, or underground craft and energize it with the hustler’s drive.” Indeed, these are qualities that most musicians have needed. But black artists in Chicago who developed these attributes could also rely on some reinforcement.

While Forrest illustrates how such performers had to build such qualities from within, some institutional support also existed for the kind of education he mentioned, and many times that came down to committed faculty. Families of young musicians in Chicago sought out the high schools in African American neighborhoods that had solid music programs and teachers who were more than adept. Saxophonist Willie Henderson and trombonist Willie Woods still credit the discipline they learned from band teacher Louis Whitworth at Wendell Phillips High School in Bronzeville. Captain Walter Dyett, who taught at Wendell Phillips and DuSable high schools from 1935 into the 1960s, became one of the most admired teachers. A graduate of VanderCook College of Music with a master’s degree from Chicago Musical College, Dyett’s students included Nat King Cole, saxophonists Johnny Griffin and Von Freeman (also an arranger at Vee-Jay), and many other jazz heroes. Dyett also taught future R&B musicians like violinist-turned-guitarist Bo Diddley and Morris Jennings, later a Chess Records session drummer. Many of these artists have commented on their teacher’s musical expertise, tough methods, and warm heart. His professional background and a supportive community embodied the qualities that later scholars of education would describe as essential. Another drummer, Marshall Thompson, who would switch to singing, added that Dyett’s pedagogy might seem unorthodox to some: “Capt. Walter Dyett started me off,” Thompson said. “He was one of the greatest musicians in the world. He’d throw that stick at you if you played the wrong note. He’d throw that stick right at your face. It was amazing, we had a thirty-piece orchestra and he could tell who was playing wrong.”

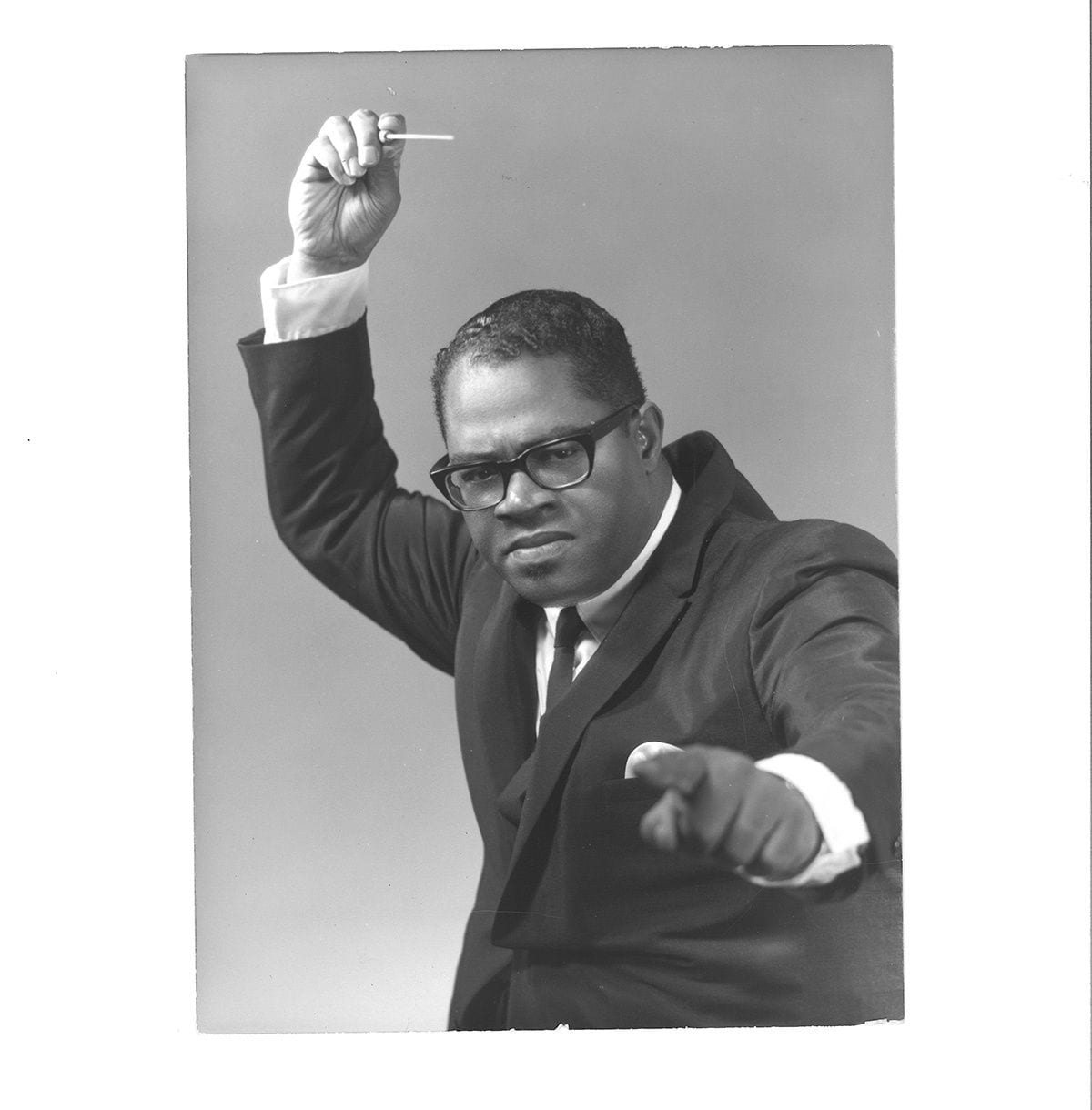

Budding musicians also honed their skills through higher education. Between 1941 and 1964, the proportion of blacks who completed college rose from less than 2 percent to greater than 5 percent. As part of this trend, in 1950s Chicago more college and postgraduate educational opportunities became available to African Americans. Roosevelt University was founded in 1945 as faculty left the city’s YMCA College to protest that institution’s quotas on black and Jewish students. By September 1954, Roosevelt could boast of a fall enrollment of 3,500 students in its schools of arts, sciences, commerce, and music. This was part of a local wave of 90,000 college students, including 11,600 in the city’s three junior colleges. Alabama-born James Mack was one such student. His classical music education included bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Roosevelt in the 1950s. During the next decade he would mentor a host of future R&B stars at Crane Junior College before becoming in demand as an arranger. Another arranger, Charles Stepney, attended Wilson Junior College and Roosevelt. In the late 1960s he would apply experimental compositional theories to R&B, blues, and rock.

James Mack. Courtesy of Shelley Fisher. (University of Chicago Press)

- Aaron Cohen - "Move On Up"

- Aaron Cohen : Move On Up – Chicago Soul Music & Black Cultural ...

- Aaron Cohen - "Move On Up" - Duane Powell

- Aaron Cohen - "Move On Up" - Duane Powell | Seminary Co-op ...

- Aaron Cohen (@aaroncohenwords) | Twitter

- Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power: Aaron ...

- Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power, Cohen