If you turn on television at night and you see picture of a young person who was a suicide bomber, in your mind, it’s incomprehensible how someone could do that. But to those people inside the system of values, that’s totally acceptable.

— Nicky Barnes

Nicky Barnes has read books. He says he started reading seriously in prison, following a conviction for heroin possession, at which point he was inspired to give up using and pursue selling (“It’s what the American dream is all about, getting money and getting things”). He names Melville and Hawthorne as well as Shakespeare, but he’s partial to paraphrasing Machiavelli. “He said there’s no right or no wrong, it’s he who has the biggest guns who determines what’s right and what’s wrong. But to us,” says Barnes, “It meant that if you’re in power, you got to be vicious.”

To illustrate, Marc Levin’s documentary, Mr. Untouchable, here shows blood, a series of crime scene photos accompanied by sirens and punctuated by Assistant U.S. Attorney Benito Romano’s commentary: “They enforced discipline. They protected themselves by deciding on and ordering the murders of anyone they suspected of being a threat to them.” Such viciousness was not personal, but “business,” according to Barnes and his former associates, including Leon “Scrap” Batts and Joseph “Jazz” Hayden. They saw themselves as “sidewalk executives,” modeled on mainstream success stories. “People that are locked out,” says Hayden, “have to find some innovative way to get in.”

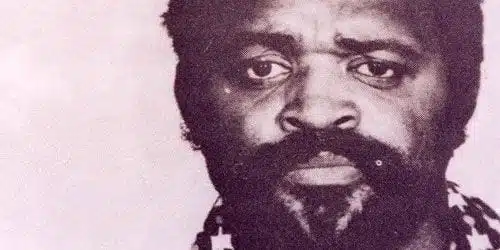

Barnes’ “way” was less innovative than effective. Still, as the film shows, it follows the sort of rationalizations that frame most rises to “power.” A product and emblem of his moment, the 74-year-old former heroin kingpin recalls his glory days as the “Al Capone of Harlem” while obscured by shadows and seated at the head of a giant boardroom-like table. An intertitle explains that Barnes “disappeared” in 1984 (this following his agreement to turn state’s evidence against his own organization and his common-law wife Thelma Grant). Now he appears neither tough nor repentant. Instead, he looks like a caricature, close-ups emphasizing his Rolex and cufflinks as he fingers a bullet or waves his hands over stacks of cash. He used to be notorious and fearsome, so assured of his power that he posed for the cover of the 1977 New York Times Magazine article that gives the film its title.

Brutal and outrageous as it may sound, Barnes’ life story is old news. Levin’s film draws from Barnes’ 2003 autobiography, Mr. Untouchable: My Crimes and Punishments (written with Tom Folsom) and revisits interviews and images used in last year’s “Nicky Barnes” episode of American Gangster on BET. Barnes serves as a minor character in Ridley Scott’s movie, also called American Gangster, where he is played by Cuba Gooding Jr. in a furry pimp’s hat. Both the documentaries submit that Barnes was a brilliant self-promoter, until he wasn’t — that is, until he stepped too far and essentially solicited President Jimmy Carter’s attention by appearing on the magazine cover in a red, white, and blue tie, which Barnes says marks his entrepreneurial spirit, his understanding of the American Dream.

This understanding informs Levin’s documentary. The photo represents a combinatory form of power and delusion, a sense of invincibility that holds to this day, at least in Barnes’ self-performance. But for all his swaggering self-confidence, Barnes remains just one piece in a vast, ongoing machine. “I have been asked,” he says, leaned back in his executive’s chair, “whether I as a dealer was being a tool of the white man. That’s probably a question that I just can’t answer.” It’s also a question Mr. Untouchable can’t let go.

On one level, the documentary delivers the usual exotica. Barnes developed a taste for jewelry and fine cars; he had much younger girlfriends (“That was one of my excesses, women,” a point underscored by “Sexual Healing” on the soundtrack); he gave his heroin colorful names to attract buyers and employed bare-chested women to process it (now a familiar image in films about the industry, from New Jack City to We Own the Night). More interestingly, the film shows how he borrowed from the Italian mafia and the Koran in organizing his business; his seven-man council maintained a seven-word mantra, “Treat My Brother As I Treat Myself,” that Barnes describes as having “a mystical dynamic as we said it.” Challenged over his use of the Koran in an American business model, he explains, “We can take from it those elements that expand us as human beings and unify us as a group, the same way the Italians do with the Bible.”

Barnes’ combining of cultural bits and pieces is as self-serving as that of other success stories. As noted by NYPD detective Larry Gerhold, he managed his self-image within “the community,” looking after small business owners and handing out turkeys on holidays (again, much like New Jack City‘s Nino Brown). As the film shows Black Santa, Gerhold observes bleakly that Barnes “was giving something back to the community that he was raping, and abusing, and killing.” Again, Barnes doesn’t answer the question provoked by such hypocrisy, but the film poses it repeatedly, showing how closely Barnes follows the model of other entrepreneurs, politicians, and stars who similarly exploit their seeming communities.

Barnes cultivated his celebrity (“Everywhere we went,” says Batts, “it was like we were known”) and worked the system of racism that simultaneously restrained and motivated him. Barnes’ longtime lawyer, David Breitbart, remembers being named “an honorary nigger” following the first case they beat. After the next one, he says, he was confused when Barnes renamed him an “honorary black man.” When Breitbart asked why, Barnes clarified: “David, we don’t hang out with niggers.”

The distinction only mattered within the group, but there, it was crucial. If Breitbart lived another life apart from his super-profitable gig with the “Black Godfather’s” operation, Barnes and his crew had to make their way differently each day. Still, the film argues, he was able to work other men’s ambitions to his advantage. His eventual dealings with the state, his agreement in exchange for evidence, were endorsed by an ambitious U.S. federal attorney named Rudolph Giuliani. Both Barnes and Frank Lucas (subject of Scott’s film and a 2007 episode of American Gangster) have recently endorsed Giuliani for president, calling him a “man of principle.” And again, the principle at issue may not be plain to everyone, but “to those people inside the system of values, that’s totally acceptable.”