The Music of Heatmiser will be received by listeners in at least two ways. For fans of the late Elliott Smith, who took his life 20 years ago in October 2003, it will be cherished as an artifact of his early band, which provided him with a crucial step toward the fame he ultimately achieved. For others, this album is an important document of the music scene in Portland, Oregon, during the early 1990s, when the underground there (and elsewhere) was being transformed in numerous ways. Put differently, Heatmiser and The Music of Heatmiser should not necessarily be reduced to Smith. This archival release involves the story of a band.

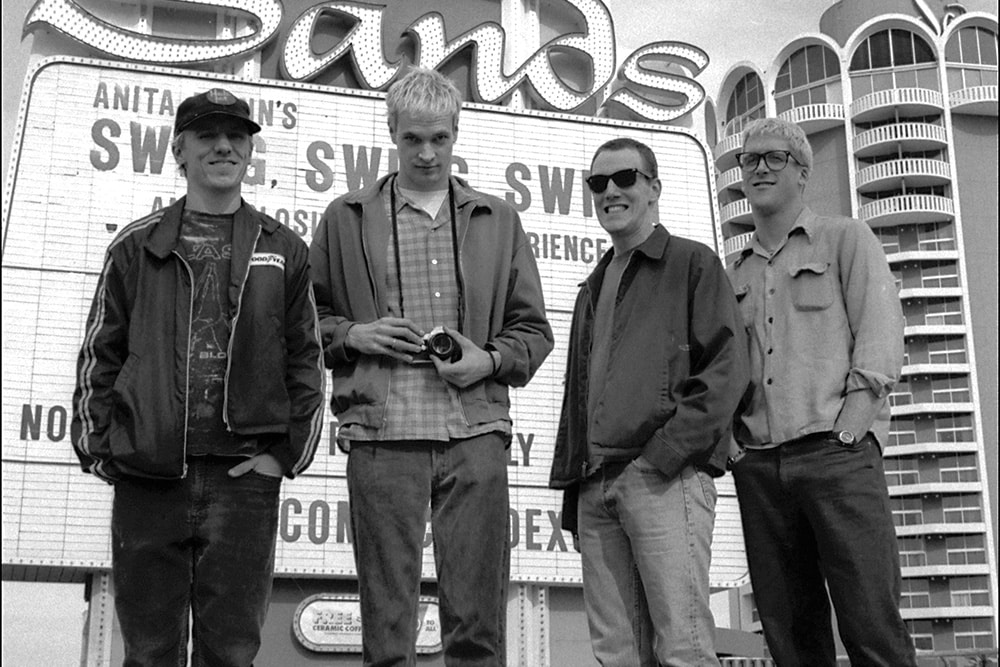

The early beginnings of Heatmiser originate at Hampshire, a small liberal arts college known for its spirit of experimentation. Situated in the Pioneer Valley of western Massachusetts, it is part of the same geography that produced Dinosaur Jr., Sebadoh, Pixies, and Buffalo Tom. Whether there is a certain terroir for indie rock in this area is a good question. Smith met Neil Gust, Heatmiser’s co-founder, while they were students at Hampshire, where they started the band Swimming Jesus. After graduation in 1991, they relocated to Portland, where Heatmiser took shape with Tony Lash (drums), a high school friend of Smith, along with Brandt Peterson (bass). Peterson was later replaced by Sam Coomes, currently of the band Quasi.

Though Smith had been actively playing and recording music since high school, Heatmiser was his first genuine band, albeit a transitory one. Between 1991 and 1996, they produced three studio albums – Dead Air (1993), Cop and Speeder (1994), and Mic City Sons (1996) – to increasing popular and critical acclaim. Intra-group tensions also accompanied this momentum. Concurrent with his involvement with Heatmiser, Smith began releasing solo work with his debut LP, Roman Candle (1994), and his sophomore effort, Elliott Smith (1995), which created a conflict in priorities. Heatmiser split just prior to the release of Mic City Sons, leaving Smith to his own devices and eventual fame.

The Music of Heatmiser is consequently somewhat of a corrective, detailing what Smith and his bandmates were up to before his stardom as a solo artist would overshadow his beginnings. From a documentary standpoint, this LP is a hybrid work. It opens with six tracks from a 1992 publicity cassette titled The Music of Heatmiser, which they self-released and sold at shows. Added to this central element is an eclectic range of material: three singles recorded for the Portland label Cavity Search; six demos for songs that would appear on Dead Air; seven unreleased recordings, including a cover of the Beatles‘ “Revolution”; and seven tracks from a live appearance in 1993 on KBOO, a community radio station in Portland. These 29 tracks at 72 minutes provide a holistic sense of what Heatmiser were like starting out, whether live, test-driving songs, or in (relatively) polished form.

The Music of Heatmiser also provides listeners with grounds for speculation about why Smith decided to strike out on his own. It forms a contrast with much of Smith’s solo work. Unlike the introspective, lo-fi, acoustic work found on his LPs Either/Or (1997) and XO (1998), the music on this record is decidedly that of a band with two singer-songwriters at the helm. Given their relative youth, The Music of Heatmiser reflects a group finding themselves by going in different directions, as if trying to divine a wellspring for continual inspiration.

The result is that The Music of Heatmiser is somewhat hit or miss, depending on your taste. It would be easy to classify this album as a document of the grunge scene in the Pacific Northwest, but this take isn’t quite right. Calling it grunge adjacent is more accurate. Tracks like “Bottle Rocket”, “Just a Little Prick”, and “Dirt” definitely possess the bellowing masculine swagger of early grunge. However, the excellent opening track “Lowlife” is a post-hardcore composition with a pop chorus akin to Hüsker Dü or Squirrel Bait. The third track, “Buick”, approaches a funky, party bounce similar to the sound of the early Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The Cavity Search singles demonstrate continued experimentation. “Can’t Be Touched” has a classic Rolling Stones vibe, while “Wake” channels the Minutemen. Among the unreleased tracks, “Laying Low” has a conventional, radio-friendly, hard rock attitude that’s both skilled in execution and unremarkable in its impact. This mix of proficiency and admitted blandness also holds true for “Father Song”, “Glamourine”, and “Meatline”. One can actively hear Heatmiser confronting that proverbial dilemma of balancing artistic impulses with commercial demands. Some concession ensues. The epitome of this compromise is their rollicking cover of the Beatles’ “Revolution”, a faithful rendition originally recorded for an ad agency.

Yet, Heatmiser didn’t sell out. Re-mixed under the careful artistic direction of Tony Lash, there is a nice symmetry to The Music of Heatmiser with the final seven tracks, drawn from their live appearance on KBOO in 1993, which revisit the earlier compositions on the record. The Music of Heatmiser begins and ends with “Lowlife”. These live versions are looser, more raucous, and give a stronger sense of the band’s chemistry. There is a ceaseless energy and resistant urgency with these last songs. “Still” and “Don’t Look Down” are standouts. Perhaps above all, there is a sense of enjoyment, even when the lyrics trend toward the downward side of life.

The same cannot be said of Smith’s solo career. The Music of Heatmiser highlights a period when Smith favored collaboration and a regular, popular audience. The albums under his name suggest something different. Grunge didn’t produce many solo artists. The genre was band-oriented by definition. Conjuring the spirit of figures like Nick Drake and John Lennon, Smith’s solo recordings went in a less public-facing direction. They often sound like they are sung for an audience of one. Even with bright production, they can possess an isolation and haunted interiority that is essentially absent in The Music of Heatmiser.

It is ultimately unanswerable as to why the apparatus of a band became insufficient for Smith. His inwardness and growing social distance were not limited, of course, to his music. Abetted by addiction, he progressively abandoned a number of structures involving lovers, friends, bandmates, and family that could have provided a sense of security and safety. The distressing paradox of Smith is that the more he seemingly manifested himself, the more self-destructive he became.

Yet, instead of letting The Music of Heatmiser become another epitaph for Smith, let it stand more positively for a one-time band of promise. The timing of its release appears calibrated to the 20th anniversary of Smith’s passing. But Gust is still active with his follow-up project, No. 2. Though Coomes was not involved with the recordings on this LP, he is still writing and touring with the excellent Quasi. Let’s be grateful for Smith’s legacy while celebrating those still with us.