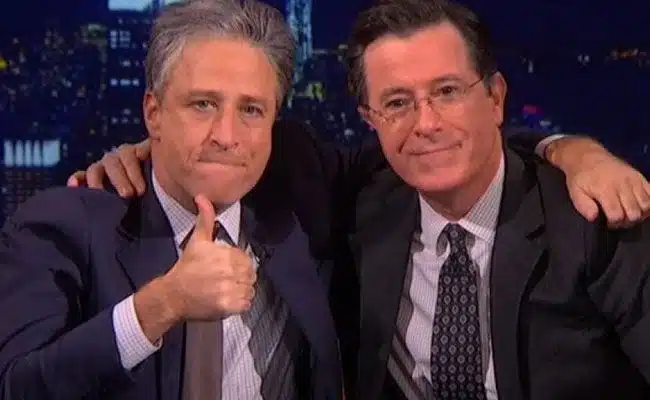

When Jon Stewart’s version of The Daily Show concluded on the 6th of August of this year, Stewart’s legacy, and that of his counterpart and long-time collaborator Stephen Colbert, was already firmly established. Beyond the ratings, aside from the accolades (including Emmys, Peabody Awards, Satellite, Critic’s Choice and Television Critic’s Awards), each show had become entrenched filters in the dissemination of news and culture, with each host – both Stewart’s faux newsreader as first responder to the day’s events and Colbert’s meta-ironic pundit caricature imploding its partisan positioning –offering indispensable satirical commentary on the day’s events.

By the end of Stewart’s run, the sensibility of the show he reinvented had stretched into every corner of the news spectrum, with several official and unofficial spin-offs each using its template to explore their own distinct televisual niche. Colbert’s The Colbert Report had used the language of celebrity punditry to expose the hack partisan bias that too frequently paralyses rational debate on 24 hour news networks. Larry Wilmore’s The Nightly Show continues to use the discussion forum format to interrogate the inequalities of race and class that often go unspoken. John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight uses the language of longer-form investigative journalism to expose the fundamental hypocrisies beneath the sound bite exterior of complex issues. All of these self-reflexive commentaries – on the media, on politics, on the relationship between the viewer and the sharply dressed talking head on TV — stem directly from Jon Stewart’s original show, and the ingenious way in which it used the language of the television news bulletins to dissect the spurious discourses perpetuated, often unspoken, in the fields of politics and the media.

It was in their respective final episodes — each uniquely designed to reflect upon their hosts’ idiosyncrasies — that both Stewart and Colbert’s shows best managed to playfully summarise their program’s mission statements, and the legacies that each left behind. Colbert followed through on the full absurdity of his character’s histrionic narcissism, killing-not-killing him into immortality, and Stewart threw a raucous party for his friends, thanking his collaborators and reminding the world that neither bullshit, nor the opportunity for real conversation, ever ends.

* * *

In the lead up to the final episode under Stewart’s tenure, The Daily Show had been reflecting upon its host’s contributions to American discourse in the most sarcastic way possible: showing clip packages of his bad singing, his self-depreciating interviews, his terrible accents; all signing off with escalating misspellings of his name. Whenever a current guest would lean in to inform Stewart that he would be dearly missed he waved the suggestion away, uncomfortably modest. In a sense, this attempt to downplay the sanctifying of Stewart was fair; although the man and his writers had given poignant satirical context to some truly despairing material over the years, their day-to-day job was always primarily to spin a half hour of gags out of almost nothing; trying to separate the social commentator from the hamster on the comedy wheel was somewhat missing the point. Nonetheless, it was impossible to not get a sense of Stewart’s impact on contemporary culture.

To hear members of the news media like Rachel Maddow and Richard Engel reflect upon his legacy, Stewart had served a form of community service. At the very least, his show was a way to sugar-coat the news of the day, a bulletin for comedy viewers who might learn something in spite of themselves. At its best, however, it was a wake-up call — a means of chastising politicians and the commentariat into fact checking their work and being more responsible with their rhetoric, lest they find themselves shamed on Comedy Central that evening.

Of course, if one had payed any attention over the intervening years — and as Stewart himself repeatedly explained – the exact opposite of this appeared to be true. With the proliferation of the 24 hour news cycle, with patriotism and the existential dread of terrorism offering easy deflections to short circuit reasoned debate, with the news media frequently whipping ‘Breaking News’ into speculation and sensationalism — all of which escalated exponentially while Stewart watched — The Daily Show seemed to merely be fighting a rising tide of hysterical hyperbole.

In truth, the show, and its host, were never static, disaffected comic observers, firing off criticism from the sidelines. They were participants in a devolving discussion, compelled to adapt and change themselves to meet the shifting sociopolitical climate they sought to comically reflect.

***

For the first few years of its lifespan, The Daily Show appeared to be little more than a conveyer belt for topical gags riffed off of a handful of the day’s major and more esoteric stories. Under the three years of its first host, Craig Kilborn, it played more as a televised odd-spot column, smirking at the headlines, trawling the country for local crackpots with absurd beliefs that could be mockingly filmed for mean-spirited field pieces, and punctuated with knowingly superficial interview banter with minor celebrities. It was a parody of news programs, aping their gravitas but willfully devoid of content.

When Kilborn left and Stewart took over the changes were at first relatively imperceptible. Gone were some of the cheesier gimmicks (‘5 Question’ and ‘Dance, Dance, Dance’) and the contemptuous tone to the field pieces gradually eased, but the show remained geared toward spinning superficial quips from a handful of the day’s events.

And then the 2000 election happened.

George W. Bush and Al Gore ran against each other for the office of the President of the United States, engaging in one of the most hostile, protracted, and labyrinthine electoral processes in history. With the lingering Clinton/Lewinski sex scandal embarrassing the Democratic party and some truly vile dirty tricks from the Bush campaign clouding the Republican nomination, the whole campaign began ugly and only got worse. By the time the entire process had collapsed into a stalemate tie – because a bunch of Florida residents couldn’t use push cards – America was suddenly watching the democratic process be turned over to the shady machinations of a partisan political machine that cared little for the rule of law (something Justice Scalia, would later repeatedly tell people to just ‘get over’.)

Newscasters, in the interests of remaining ‘objective’ reported the claim and counterclaim of every participant no matter how unsubstantiated or skewed. Partisan suits squabbled over unwritten legalities. There were lengthy debates over the difference between a ‘dimpled’ and ‘hanging’ chad. People had to learn what a ‘chad’ even was. The world had suddenly become utterly absurd. So logically, an absurd commentator was required.

Looking back, it’s no surprise that the coverage of the election won The Daily Show the first of its two Peabody Awards; Stewart not only provided context for the escalating lunacy of the time, his was one of the few voices able, through the allowance of satire, to actually call out the ridiculousness of a democratic process held hostage by the entitlement and greed of the few.

A year later, when the aftermath of the September 11 attacks gave rise to the bunkered panic-station sensationalism of the 24 hour news networks — of colour-coded terror alerts and the magic powers of duct tape — Stewart returned to the air to simply ask his audience if they were okay, and to remind them that in the depths of grief can come resolve. Over the following months of insanity it was The Daily Show, a comedy program, that frequently seemed to be the only voice of reason, cutting through the sensationalism and panic to remind people of the baseline of normality beneath the hysteria.

From that point onward, while never abandoning his principle duty to make dick jokes and cheap puns, Stewart became a powerful voice in the nation’s capacity for introspection, simply because he, unlike so many others in the media landscape, was willing to try. After Hurricane Katrina, his voice captured the raw, angry horror of a nation trying to process the callousness and ineptitude of a government that had abandoned its own people to squalor and death. He watched the world go to war in Iraq on the back of grotesquely insubstantial evidence. As ‘WMDs’ and ‘yellow cake uranium’ and Colin Powell waving a vile of anthrax at the United Nations were ubiquitous, Stewart was one of the few voices in the media consistently calling those ‘facts’ into question. He charted the disappointment of the promises of ‘change’ and ‘hope’ offered by the Obama White House, speaking truth through the guise of farce, as NSA spying went on unchecked, drone bombing programs escalated seemingly without oversight, and further reports of torture and rendition and overreach went on unabated.

As the global financial crisis unfolded, unleashed by the corruptive practices of a system engineered for exploitation, Stewart was one of the few to hold not only the banks and lenders to scrutiny, but the hypocrisy of those in the media who had failed in their duty of care. Jim Cramer, a pundit for CNBC, had feverishly spruiked the companies responsible for the fall despite their illegal actions (and with giddy sound effects), right up until their collapse; then, while the private investors and homeowners who had followed his advice lost everything, had condemned the victims, dodging any culpability and lecturing them on their foolishness. But famously, as Cramer feigned indignation that Stewart would dare question his integrity, all Stewart had to do was run video of his myriad promises to watch him wither.

Despite the fact that Stewart was renowned for his capacity to mock the news of the day, what was most impressive was his ability to give voice to the unfathomable, embracing both the horrible absurdity of life and allowing for the silences that cannot be filled. This was perhaps best exhibited as he watched the plague of American gun violence play out over the years, escalating with each incident of murderous brutality. Over the years he became the harshest critic of this redundant spiral — the same denial and obfuscating soliloquising from defenders of gun deregulation; the same calls for change going unheeded as congress stalled into apathy — and his final commentary on the racially motivated mass murder of nine people at a church in Charleston exhibited a weary despair at this tired, seemingly eternal routine.

What became clear in his every broadcast was that Stewart hated lies — ‘bullshit’ as he would come to call it in his final show. More so, he hated the knowing systemic perpetuation of lies. The angles of intimation, speculation and faux-questioning that substituted for argument. It was why Fox news became such a ghoulish case study over the course of his tenure — an echo chamber of prescribed falsehood that confirmed itself by inference. As Stewart said at his ‘Rally to Restore Sanity’:

‘If we amplify everything we hear nothing.’

If we allow lies to stand, if we surrender ourselves to exaggeration and hysteria in all its forms, then we lose the capacity to perceive anything at all.

Despite watching the dire spectacle of these patterns unfold again and again, Stewart never surrendered to tired cynicism. He used the platform afforded him to champion good causes, and agitate for change. He praised the heroism of the 9/11 responders, and he crusaded for the passage of the First Responders Bill, a legislation that had been turned into a bartering chip in Washington politicking. Stewart held to account the mealy-mouthed politicians who publicallpagy praised the responders, but privately sank the bill that would protect them. His act of shaming was the only thing that prevented the disgusting farce from continuing unquestioned by a disinterested media. He welcomed voices like Malala Yousafzai and Jimmy Carter that supported charities and spoke out for human rights. He raised money for autism research, and helped develop and run a veteran training program to offer returned soldiers invaluable industry experience.

His comedy, too, too often dismissed as ‘pessimistic’ by those who clearly never watched the show, actually came from a place of optimism and hope. His humour was not about declaring ‘Look at how fucked up we all are’, it was about suggesting that we not keep falling face-first into the same puddles. He was disappointed in systems and rhetoric that failed, but it was only because he clearly believed that these things could function for the benefit of society, if only they were treated with the right respect (or lack of respect, where appropriate). Even when he took Fox News to task, it was not because he thought the network was an easy punching bag, or a symbol of the end times (even though it is both of those things), but because he believed that Fox could do so much better, but perversely, chose not to.

The Narcissistic, Pigheaded, Bullying, Right-wing Cheerleader

The Colbert Report spun off from The Daily Show in 2005, responding directly to the explosion of bombastic punditry filling the airwaves. Drawing heavy inspiration from figures like Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly, the ‘Colbert’ character was fashioned into a narcissistic, pigheaded, bullying, right-wing cheerleader, shamelessly subservient to corporate sponsorship and drunk on the whiff of his fantasised political clout.

On its first night it coined the idea of ‘truthiness’: the distortion of fact to fit a predetermined emotional narrative (a term so perfect it was soon incorporated into the Oxford English Dictionary). For almost a decade the show was continued to fit this definition, becoming a funhouse mirror, playing out an evolving, ironic exhibition of just how malleable reality could be when the news was given over to the self-aggrandising agenda of a charismatic zealot.

Alongside the show’s searing satiric wit, much of its genius can be traced to the real-world Stephen Colbert’s unique and expansive skill set. Colbert is an exceptional improvisational comedian, coming up through Second City and honing his craft for years on The Daily Show, and it has been that skill at sustaining, adapting and evolving a joke, that seemed to inform the show. The ‘Yes/And’ of long form comic narrative allowed it to go wandering to truly surreal lengths: the Sean Penn Metaphor-Off; the Late Night Ice Cream Battle with Jimmy Fallon; Cooking With Feminists; the Shred-Off with the Decemberists; his decade long argument with his mirror-self, his only ‘Formidable Opponent’; the Daft Punk debacle; and his eternal wars with Jimmy Fallon, the liberal bias of reality, and bears.

The Colbert Report eventually bid farewell in December of 2014 in order for its star, real-world Stephen Colbert, to move to CBS and take over the retiring David Letterman’s The Late Show. But in an ironic twist for a show gravitationally bound to the ego of its fake conservative pundit ‘Stephen Colbert’, on its final episode the show chose to celebrate community.

After faking out the audience for months with allusions to the character’s inevitable demise (‘Grimmy’ the Grim Reaper had been seen lurking around the set, pointing ominously to a dwindling clock and, one assumes, swiping office supplies) the show made the inspired decision of subverting this expectation and having Colbert — by accidentally killing Grimmy himself — ascend to a state of omnipotent godhood, allowing one of the most enduring satiric characters of all time to finally take his place amongst the pantheon of American folklore, ushered into eternity with Santa Claus, Unicorn Abraham Lincoln, and …Alex Trebek?

Okay. Sure.

While riding into the nethersphere of iconography, Colbert’s final act — letting the mask partially slip — was to send a heartfelt thanks to the ‘Colbert Nation’, the fans and community that were an integral part of the success of his show.

As his final episode, taking its last bow, elegantly acknowledged: without the Colbert Nation he would never have appeared, in character, before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, delivered his blisteringly subversive speech at the White House Correspondents Association Dinner, run for president, or in the saga of the Super Pac (perhaps his greatest achievement), had his audience raise a fund he was able to exploit for practically any insidious, disingenuous or libellous act he could imagine, unequivocally revealing just how corrupt and lawless the entire system of campaign funding and advertising still remains in politics.

The character of Stephen Colbert (‘The T is silent, bitch’) was an egomaniacal blowhard trying to remake the country into his own conservative fantasy, but that character needed, nay, required a legion of chanting, ecstatic fans, in on the joke and feeding him with ironic adoration that masked a genuine affection. One joke — the blowhard pundit short on facts and bloated on partisan rhetoric — had grown and shifted and expanded itself into the fully-formed leader of a cultural empire.

As Colbert stated in his climb to the stars, it sure as hell was fun.

When the show ended, despite the host’s grand ascent into the metaphysical ether , he still threw back to Jon at the original show’s desk, concluding his protracted voyage into absurdity by folding it back into The Daily Show’s ongoing exploration of same.

***

Almost a year later and The Daily Show’s finalé was an even more overt opportunity to reflect upon its own history, and the collaboration that gave the show life. Rather than dwell sycophantically on Stewart’s achievements, the show celebrated the contributions, not only of its host, but of its writers, producers, staff and audience.

All of the correspondents returned to pay their respects, and to be thanked in return. Even those who had seemingly left the show on bad terms returned. Craig Kilbourne appeared, acknowledging the show’s lineage. John McCain, one-time favoured guest of the program (who had refused to return after Jon criticised some of his behaviour in the lead up to his run for President in 2008) appeared in a pre-recorded farewell. Impressively, the show managed to address the sadness around a falling out between Wyatt Cenac and Jon into a beautiful and warm tribute — not downplaying it, or ignoring it, or letting it overwhelm. It just became an opportunity for two people who respected one another’s work to reconnect. It hung on an invitation to talk, and a couple of welcome smiles.

Perfect.

In the penultimate episode of the show, Stewart had sought to address some of the more inflated hyperbole of those who had declared, in their eulogies for his tenure, that the show had ever ‘eviscerated’ the issues it addressed, or ‘demolished’ the subjects is presented. That, he said, was never the purpose, and certainly it was never the result (as the appearance of Gitmo, the Elmo-clone terror-suspect stranded in a Guantanamo limbo hilariously reminded the audience: there was plenty still wrong with the world).

Instead, as Stewart made clear in his final address to the audience at home, his show was a conversation. An invitation to discuss, through the levelling power of humour, through the respectful exchange of ideas, the ways in which we as a community could escape feeling overwhelmed or apathetic toward one another. Each night, unpacking the day’s events, he invited us to converse. With political leaders, with authors and thinkers and celebrities. With phony correspondents. With each other, and with ourselves. His show was a chance, in the guise of light entertainment, to invite true debate and reasoned discussion. He welcomed guests of all beliefs and political leanings, providing them a space to air their opinions — and to have those opinions challenged.

It was a final episode that acknowledged both its successes and failures; one that contextualised the past 17 years into a conversation — one in which we could learn and laugh — by allowing us to entertain other people’s perspectives. (The finalé even literalised this invitation to share another’s point of view by presenting his first person perspective tour of the backstage production of the program — a loving homage to (read: rip off from) the famous one-take steadycam shot in Stewart’s favourite film, Goodfellas.)

Even though every show affected a tone of dispensability, responding to the day’s events on the treadmill of an endlessly evolving news cycle – en masse they were more. They taught us how to disseminate the world: critically, morally, with context, and with humour and heart. They were not product, but training in discourse. Not about making didactic statements, but about allowing us in to the grammar with which we make meaning.

So it was fitting, then, that when Stephen Colbert returned to say his farewell under the guise of a Lord of the Rings bit (declaring himself Samwise to Stewart’s Frodo, the two of them on their suicidal ascent to Mount Doom, fighting against the inexorable evil of media complacency), he spoke for the correspondents and the staff and the viewers at home to offer the reply that Stewart would otherwise never directly hear. Colbert said ‘Thank you’, expressing his gratitude for the opportunity to grow under his tutelage, to participate in his exploration of discourse and to learn from his example.

For almost 17 years that’s what Stewart provided. He offered his audience a glimpse of his world — their worlds — not free from the bullshit, but where the bullshit could be counteracted with snark, or passion, or joy. He took the persistent, aching rage of a world that spewed hypocrisy and bile and conflict into our souls, and showed us how to alchemise that din into comedy, or action, or at the very least awareness.

Thus, Stewart’s tenure on the show concluded with Bruce Springsteen — Stewart’s favourite musician (and mine) performing two songs that were perfect encapsulations of his time in the host chair: ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’, a song about broken people striving together to find a home worthy of the promises they still believe in, and ‘Born to Run’, a song about the urge to flee from stagnation, to chase the promise of a future not mired in the compromised expectations of the past.

‘Nothing ends,’ Stewart reminded his audience before credits rolled. And with that, he was gone. The conversation, he promised, is paused, but ongoing, and the chance to do better always possible. Stewart’s Daily Show reminded us that humour is about two disparate states in tension, revelling in their contrast. Intelligence and stupidity, civility and insolence, order and anarchy. This was the engine for both Stewart and Colbert’s shows’ over the years, but it was also at the heart of their agendas: to make us see the conversation within ourselves, between our inner cynics and optimists, and to yearn to do better whenever we could.