I was some sort of piece of charcoal being worked upon in those studio sessions.

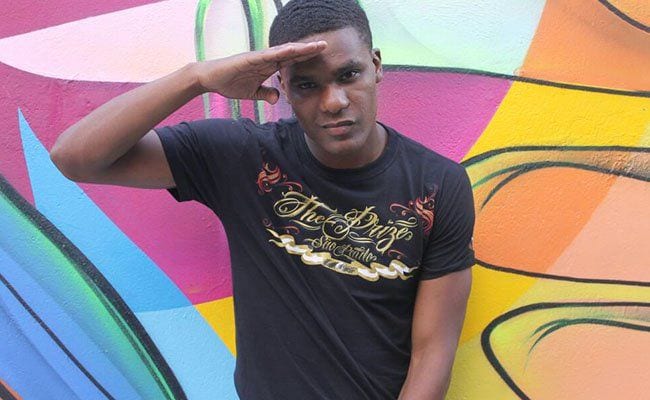

One of Brazilian hip-hop’s brightest fixtures (and a virtual unknown outside his homeland), Terra Preta has been hard at work, forging an identity as a contending rapper in his native country these last few years. His distinctive delivery — a smooth blend of soft, caramel croons and breathless, hurtling raps — has earned him a niche in Brazil’s flourishing DJ culture.

His rough and tumble beginnings as a poverty-stricken child is not a story uncommon in the world of pop music. But his unusual way of condensing the most difficult experiences into a lushly gorgeous production of sound is what distinguishes him from the rest of his country’s upstarts.

Terra Preta (a stage name meaning “black earth” in Portuguese) works a particular seduction with sea-breeze harmonies underpinned by heavy, bottom-end grooves. His chancy way with a honeyed melody and the sensual pulse of Afro-Brazilian rhythms calls to mind the vibrant colours of his São Paulo’s coastal ridges; beautiful and exhilarating all at once.

Already the rapper had been honing his art on a number of mixtapes before his official album debut. His first mixtape, Milionário em Treinamento, was an underground sensation in Brazil, alerting the public to a talent who could respectfully bridge the local sounds of his home city with the flashy exuberance of mainstream American hip-hop. Terra Preta, however, would truly come into his own as an artist with his proper debut, Homem Figa, Vol. 1. Full of irresistibly juicy beats, smoky vocals and lush harmonies, Homem Figa Vol. 1 signaled a new artist to rival some of his nation’s most respected hip-hop contemporaries like Marcelo D2 and Criolo.

Though the budget for the independent artist was understandably limited, Terra managed to gain much mileage with the album’s tight arrangements and solid songwriting. Leading single, “Nasce, Cresce e Morre” exemplified the best of the rapper’s traits: a knack for a hard, snapping beat, steady lyrical flows, and a sharply-tuned pop instinct. Catchy, immediate and crowd-pleasing, the single offered its proof-in-the-pudding assertion as a worthy staple of mainstream radio.

The rest of the album lightly flirts with popular Brazilian music traditions like baile funk, maracatu, samba, and MPB. Subtly laced with Afro-Brazilian percussion and rhythms, Homem Figa is successful in fostering a crossover appeal that goes down with hip-hop heads as easily as with pop music enthusiasts. Musically name-checking many disparate influences like Brand Nubian, Jorge Ben, Maxwell and Sugar Minott, Homem Figa explores hip-hop and R&B through a framework that is unequivocally Brazillian. Tracks like “Nunca Imaginei” and “Andarilho” demonstrate an R&B of delicate samba persuasion. The album’s more bassy exploits of “Os Muleke é Zika” and “Todo Dia Nasce Uma Estrela” are stretched to the booming depths of hip-hop’s bottom end. And on “Lutar Até As Últimas”, the rapper introduces a Brazilian reggae ringing with sunny pop hooks and sumptuous harmonies, thick and smooth like cocoa butter. With his debut, Terra Preta cements his status as one of Brazil’s more exciting prodigies and he continues to develop a fan base, bringing his music to stages across the country.

As a live performer, Terra is a solid presence, a songwriter who delivers his craft with the practiced hand of a sincere and skilled artist. His live renditions of his studio recordings are fresh and dynamic and they reveal a confidence unsullied by a needless desire to impress. To date, he has several albums worth of material and he continues to record at a relentless and fearless pace, keeping time with the many twists and turns that find their way into hip-hop-based music. The gorgeously dreamy single “Amanhã” (2016) presents an artist who has crossed the threshold of adolescence into the mannered and reflective reserves of adulthood. That same year’s “A Fórmula Mágica Da Paz” redesigns Teddy Pendergrass funk into a souled-out hip-hop jam of lustrous romance.

Building a musical narrative with the luminous colours of his native Brazil, Terra Preta continues, along with the pantheon of like-minded artists, to provide hip-hop with its most enduring and imaginative constituent: an earnest voice fuelled by a raging and passionate soul.

* * *

Please tell me about your life growing up in Brazil as a child and teenager.

Well, I’m the kid who survived the chaotic 2000s. My parents are from the northeast region in Brazil and they came to São Paulo in the ’80s. They were very religious, so my first few years of life were more disciplined. Ever since I was little I identified myself with the choirs and did everything to sing in the church. That was the part that made me more focused; I didn’t care much about the rest.

My parents have always kept me close when they were married, so I can say that I was well protected. Their mentality was that I should stay away from the troubles of the outside world, so at home I didn’t have TV, I couldn’t listen to mundane songs, nor play with toys that resembled weapons or that indicated violence. But inevitably, I was facing violence, seeing people being shot…The situation was so intense that when I was six, I found my neighbour Robertão’s dead body in a dump right in front of my house. I thought it was a soccer ball and asked a lady to pick it up for me. When she pulled it up, instead of a ball came his head.

That sort of situation was common for anyone who lived in the outskirts of São Paulo at the time. These were the cold years of the transition between the ’90s and the 2000s.

When I was 11-years-old my parents didn’t go to church anymore, so things got easier for me. I started listening to music that I wasn’t allowed to listen to before. Later, in my teenage years, they split. We had changed the neighbourhood in search for a better atmosphere, but things weren’t much different than the last place. In my junior year my school was so violent that one day some UN representatives went there to pay a visit, as there had been two homicides of students within the school year.

I literally felt like I was living in hell and the only thing that could take my mind to a different place was whenever I listened to hip-hop, spending hours writing poetry and lyrics, while imagining a different future for myself. I was always afraid of being shot or getting involved in some sort of mess, so that was the best way to distract myself: reading, listening to music and writing.

How were you first introduced to hip-hop and what were some of your first musical influences?

I first listened to rap in1996. It was “Thug Luv” by Bone Thugs & Tu Pac and that became engraved in my head. I was too young to understand what was going on, but I was so stunned by their flow. That beat was sick! I had no idea what genre that was. Those gun-cocked sounds and twelve caliber shots that were sampled in the song created a really tense atmosphere with which I connected. That reminded me of all the places I grew up in. Then, around 2000, when I moved to a new neighbourhood, Grajaú, I became familiar with the people from the new school and in very little time and I met some other guys who enjoyed rap-music.

Together we formed a rap group. We were some sort of Wu Tang Clan from the neighbourhood and we got ourselves some notoriety by singing at some events at our school and throughout the city. Side by side with these guys I had the opportunity to listen to all kinds of rap from the early ’00s. Me and my friend Ezse watched the Yo MTV show that spoke about the vinyl culture in hip-hop. So we decided to roam the city looking for some old records. We ended up knowing more about hip-hop history and listened to all kinds of music that wasn’t really from our time. That helped me achieve a ‘macro’ vision about music. It was then that I started to understand more about the roots of hip-hop culture.

Your album Homem Figa Vol. 1 was produced by Stereodubs. You’d been making music before that, but this album was your proper introduction to the Brazilian public. What kinds of ideas and influences were you exploring on that album?

I had already sold 8,000 copies of my first mixtape, Milionário em Treinamento, via direct approach, and was in a frantic rhythm through São Paulo trying to get my work known around. At that time I got to know Léo Grijo. He, along with DJ LX, had already produced Flora Matos’ album and I was interested in the sound they were doing; I thought it would be an interesting idea to do something in that sense. Having a full record produced by a sole team was just what I needed.

My getting along with Léo was almost immediate and since we met in Studio, things flowed really fast. We didn’t have much time to think about the aesthetics or influences we wanted on record at the time. When they presented me with a beat I just wanted to know if that was musically grand and if I could sing in an original way atop of it. Despite doing something that was out of my comfort zone, I ventured into different styles such as reggae.

It happens that I’m some sort of chameleon when it comes to music; I can analyze the interesting elements and rapidly incorporate my own essence into it. They gave me direction and the notion of what the songs needed. I was some sort of piece of charcoal being worked upon in those studio sessions. I ended up writing on top of all the instrumentals they provided me at the time, and the rest was only a matter of arranging things in the best possible way.

Your rapping method is heavily influenced by an R&B singing style. How did that develop?

That was Tu Pac’s fault. He’s the one to blame for my singing and rhyming. When you listen to “Changes”, “Ain’t mad at cha”, “Do for Love”, and “Dear Mama”, there’s always some R&B artist in the chorus. Because of this, I began to formulate in my mind that I could rhyme and sing in my own songs. In the ’00s, R Kelly gave me the base, then Nelly made the whole thing fun, 50 Cent did this in an intriguing way by being gangsta at the same time. Later on, Trey Songz and Drake showed that this could be done with a master’s touch, so I was just convinced that singing and rhyming would be imprinting my own artistic identity on whatever I laid my voice on. Definitely, I am the guy on both verse and chorus.

There are a lot of Brazilian rappers who use traditional Brazilian music in their hip-hop. Homem Figa Vol. 1 flirted slightly with traditional Brazilian influences. But have you thought about making hip-hop music even more heavily influenced by traditional Brazilian sounds?

Yes, a guy that’s been doing it a lot is Rincon Sapiência, and I’ve been watching a lot, ever since Marcelo D2 made that a world trend. In my mind, it was always a vague idea. I like Soul, R&B. When I think about something with percussive elements, I have the feeling that the music is going to lose that hip-hop weight; that’s why I lay low about exploring regional music elements with a standout percussion element. Either way, if I ever find something that can allow me to blend these elements in a balanced way, I will be sure to jump in without thinking twice. The important thing is to have a sense of objective for everything and to keep it all in its right place.

While other hip-hop artists are exploring a minimalist approach in their music, your hip-hop grows increasingly heavy; there’s a strong emphasis on the “bottom-end” with harder beats. Your music often seems to refer to the “bass culture” of reggae. Can you discuss this element in your music?

Right now my musicality goes to where world music is going. I don’t make music with a regional appeal. The world is Dancehall, the world is Trap. I want to dominate these things as well. When I listen to “Unforgettable”, by French Montana, I think “Wow!” I can be more free-spirited, more Afro. But since I have a passion for lyrics with punch-lines, my challenge is to have something contagious, but I also want people to listen to the lyrics and think “what did he mean by that?”

That’s the great dilemma at the moment, so I chose to take a little time before releasing material. I want to reach that level of shocking people with each line while making them dance at the same time, with all the rhythms and melodies; the perfect fit for the voice in the beat.

You have flirted with some English lyrics in your music and it sounds like you could perhaps do an English-language with no problems (your English accent is quite fluent). Have you considered recording an English-language album?

That is a dream I wish to make real, soon. I’m training so that someday I can collaborate with international artists and I really want to live in California in the future. I’ve been listening to North American hip-hop my whole life without having any idea of what they were saying in the lyrics. I was just fascinated with the videos, the approach and the way those artists were behaving themselves, so when I listened to music, I just absorbed the phonetics of it. I was working on it step-by-step and it ended up giving me some notion about how to use the words. I believe that if I take my chances on R&B, it’d be easier because there isn’t such a great complexity in the words in that realm. I believe in that possibility.

What are your ideas and feelings about the hip-hop culture in Brazil? Also, how is your music received by the public in your homeland? And have you ever performed live outside of Brazil?

We are in a constant evolution. We came from a really difficult epoch [in Brazilian hip-hop]. People followed a hip-hop manual and whoever didn’t commit was persecuted and ridiculed. When I first started singing melodies over the beats, it caused the audience to react in a bad way. They only wanted to listen to rhymes and hear protest. I was seeding on sandy soil at that time. I always had to do everything twice to prove my worth, but today people are much freer to do the music they like and if you’re really good and if you have a good strategy, you will have your place. I still haven’t left the country, but I have fans in Angola, Mozambique, Portugal and other countries where they speak Portuguese.

Your most recent material, “Girlfriend” and “MMXVII Flow” explores trap music and electronica. What direction are you taking your music in now? What kinds of music do you find interesting at the moment that are influencing your work right now?

Trap music has been my vice for some time now; I feel comfortable singing some melodies and I also have a flair for rhyming. It’s a really free style of music, so I can sound either pop or visceral, depending on the situation. But for now, people don’t associate trap with well-developed lyricism.

In “MMXVII Flow” I’m sending a message about making trap and driving listeners crazy with punch-lines. I can craft melodies that stick in the mind while having something to say as well. That is an advantage. I come from a generation in which, if you wanted to rhyme, you had to have content and think well enough before speaking anything. I feel like I’m a little bit ahead in that matter and I’m solidifying my spot, ready to dominate in every sense.

Are you currently at work on a new album? What can we expect of you and your music in the near future?

I have over a hundred songs on my HD, but I don’t want to make the mistake of going out and publicizing everything in any way possible. Right now I’m patiently recording more material every day to have something that seems reliable. I think about making an album that feels well developed, where the songs tell a story and the album as a whole creates a panorama, especially in these current days, where everyone just wants to put out a knockout single and then just move on to the next one.

I believe I can be more creative and give something more special for people — not only a fast food meal. I’ve been around long enough to understand that the fastest one doesn’t always arrive first, so I want to give my audience something consistent.

Many thanks to Enrico Ribeiro for his translations for this interview. His contributions to PopMatters, past and present, are deeply appreciated.