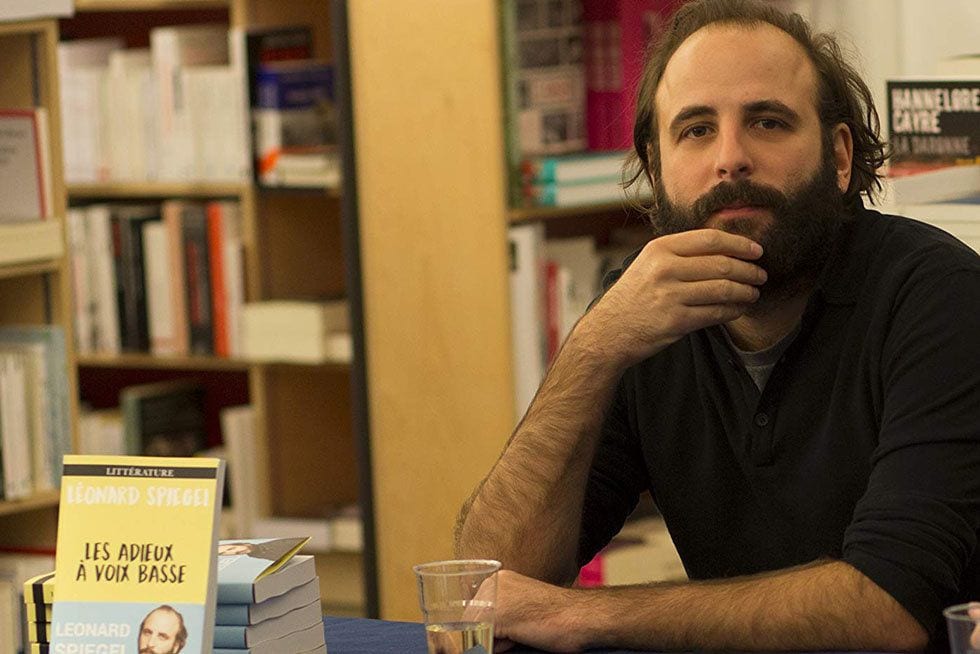

“Fewer readers, more books.” “I reject this materialistic society.” “These are narcissistic times.” Those are just a few of the cheery bon mots being lobbed around in the opening minutes of Olivier Assayas‘s argumentative but thin wannabe literary salon of a movie. A number of them are provided by the movie’s most irritating yet nevertheless liveliest character, Leonard (Vincent Macaigne). A slightly slovenly novelist who doesn’t have the energy to go online to see what people are writing about him. He can hardly be bothered to pull the thinnest of veils over the autobiographical slurry constituting his increasingly unpopular novels. He likes to proclaim his work “autofiction”, as though he were a Gallic Karl Ove Knausgård, but it seems more like the blatant navel-gazing blogging he despises so.

This habit irritates some of those around Leonard, not just his thinning readership. His agent Alain (Guillaume Canet, somewhat anaesthetized-seeming) doesn’t quite have the heart to tell Leonard that his books just aren’t selling and that maybe it’s time to try something else. Meanwhile, Alain’s wife Selena (Juliette Binoche), a popular but somewhat over-it TV actress, is peeved at Leonard’s barely fictionalized writing since the two of them are having an affair. Sure, it’s Paris, and it’s not as though he isn’t having his own thing on the side—a tryst with his house’s youthful new blonde digital-publishing maven, Laure (Christa Theret) that feels so preordained it might as well have been part of her new-hire training. Nevertheless, Selena would rather not rock the boat.

What Selena does want to do is the same as just about everyone else in Non-Fiction (Doubles vie): Argue. Whether the characters are lounging in bed, at a restaurant, or circling around each other at a party so bristling with tension that you’re just waiting for a wine glass to get thrown, they are verbally battling. Politics ripple through at times, but only on a superficially cynical level, to the consternation of Leonard’s grumpily earnest wife, Valerie (Nora Hamzawi), who works for a similarly earnest Socialist politician reviled by the movie’s salon set for being, well, they’re just not sure what.

Like people everywhere, for the most part, they argue and complain. Like people in publishing everywhere, they lament that nobody seems to read anymore. This begins somewhat interestingly, with Leonard essentially refusing to acknowledge that the world has changed, and Alain jousting with Laure over the virtues of print versus digital. But things spiral rapidly into a kind of irrelevance, as the arguments fill the kind of apocalyptic ebooks-are-coming worries that were far more prevalent several years ago. It’s difficult to imagine anybody in today’s publishing world expressing the kind of naïve digital utopianism (“tweets are modern-day haikus”) issuing from Laure without being laughed out of the room.

Assayas, who normally has a well-attuned ear for cultural nuance, radiates tensions of societal displacement throughout his sometimes spiky but more often rambling screenplay. In one promising scene Leonard gets pilloried at a bookstore event for writing fictionalized versions of people without their consent. But that fails to go much of anywhere besides Selena insisting that he not use their affair for his work. Similarly, Alain musters a sharp counterattack on the idea being foisted on him that the digital flood is inescapable by noting, “No one asks us, then it’s too late.” Which is about as cogent a summation of 21st century disruption as have ever been uttered.

Beyond the vague sense of everything being at something of a hinge point, from these potentially fracturing relationships to the nation’s once-hallowed literary culture rotting from within, there is not much holding Non-Fiction together. Assayas’s light touch with dialogue, a screenful of committed performances, and at least one solid meta-joke (wondering who they can get to perform the audiobook of Leonard’s novel, Alain suggests “Juliette Binoche”) make for a fast-moving and occasionally thoughtful romantic dramedy.

But from the filmmaker who gave us Carlos (2010) and Clouds of Sils Maria (2015), that hardly seems like enough.