In 1966 George Harrison’s passion for Indian music was continuing to grow. He took his sitar with him on his honeymoon in Barbados and practiced while his wife sunbathed. On their return to England he enthused to Maureen Cleave in the Evening Standard about Ravi’s Festival Hall concert: “I couldn’t believe it. It was just like everything you have ever thought of as great all coming out at once.” He explained his struggles to play sitar cross-legged—”I wish I could sit on the floor like Ravi”—and revealed that he had considered going to India for six years to study properly. Dreamily, he told her, “Just before I went to sleep one night, I thought what it would be like to be inside Ravi’s sitar.” Among the four Beatles, it was Harrison who led the fascination for Indian music, and he encouraged the others in the same direction. John Lennon also enthused about it to Cleave: “It’s amazing, this—so cool. Don’t the Indians appear cool to you?… This music is thousands of years old. It makes me laugh, the British going over there and telling them what to do.”

On April 6 the Beatles returned to Abbey Road Studios to create “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the most startling leap forward of their whole career. Lennon’s song, an aural recreation of an LSD trip, takes its lyrical inspiration from Timothy Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience (using lines different from those included in Ravi’s soundtrack of the previous year). It opens with a tanpura drone, has no modulation and stays on a C chord throughout, with McCartney’s bass guitar reinforcing the drone. “This was because of our interest in Indian music,” said McCartney. “We would be sitting around and at the end of an Indian album we’d go, ‘Did anyone realize they didn’t change chords?… Wow, man, that is pretty far out.’ So we began to sponge up a few of these nice ideas.” With this song, the drone was relaunched into the mainstream of Western popular music culture, and it is easy today, habituated as we are by its ubiquity in electronic music, to underestimate its impact then. As Ian MacDonald wrote, it was “like an unknown spiritual frequency tuning in.” Another psychedelic ingredient was the series of saturated tape-loops that were mixed into the song live—inspired, like Conrad Rooks, by the cut-up technique. One of these loops contained a sitar phrase played backward. Lennon’s voice was even treated in order to sound like a Tibetan lama declaiming from a Himalayan mountaintop.

Harrison’s song “Love You To,” recorded the following week, makes its Indian influence even more explicit. It is like an Indian classical recital reshaped as a three-minute pop song. The opening passage on unaccompanied sitar, played by Harrison himself, represents a brief alap, and with the entry of the tabla segues into a medium-tempo gat in teental, before stepping up to a fast gat for the last 20 seconds. The scale has flattened third and seventh notes and is thus in Dorian mode—or, as a north Indian classical musician would put it, Kafi thaat. Indeed, his melody is based on a typical phrase of Raga Kafi. The tabla player Anil Bhagwat, who had been recommended by Ayana Angadi, was asked by Harrison to play the same rhythmic cycle as Ravi had used on a specific album track, almost certainly Dhun-Kafi from Ravi’s album In London, which features an alap followed by medium and fast gats in teental. The resemblance is closest from about 2 minutes 30 seconds to 3 minutes 5 seconds in Dhun-Kafi, and both pieces open with an arpeggio on the sitar’s sympathetic strings. The most likely scenario is that, after hearing In London, George asked his sitar teacher to show him Raga Kafi, and then he worked out his own composition based on it. The result is still pop music, with overdubbed guitars, vocals and tambourine, and it is a composed piece, not improvised. Moreover, the rhythmic cycle is not authentic. It is teental quarter-sliced into beats to the bar, and it does not run continuously throughout, as it would in Indian classical music, instead stopping three times for breakdowns, while the penultimate chorus comes in a beat early (on the twelfth beat rather than the thirteenth). But the song reveals that Harrison had absorbed a great deal from listening and from his initial lessons.

These new Beatles songs did not see light of day until Revolver was released to British radio in July, by which time the smoldering timber of “Norwegian Wood” had set off what Ravi came to call the “sitar explosion” in the world of rock and pop. In 1965 there was just a handful of pop stars tentatively exploring Indian music. In 1966 it became the flavor of the year.

When the Byrds had toured America in a motor home in November 1965, they took with them one of the newly available compact cassette players. They had just two tapes, which were on constant rotation, rigged via a Fender Showman amplifier to reverberate throughout the bus. One was John Coltrane, the other Ravi Shankar. Steeped in these sounds for a month, they recorded two new songs in December that took pop into the territory of modal improvisation. “Eight Miles High” is based around a recurring four-note guitar phrase lifted from Coltrane’s Village Vanguard recording of “India”—itself an interpretation of Indian music. McGuinn plays long jazz-tinted solos on a Rickenbacker electric twelve-string against a bass-guitar drone, and the lyric has a deliberately druggy double meaning. If that was the Byrds playing Coltrane, then the second track was their Ravi Shankar number. “Why” has two extended guitar solos with a loosely Indian feel, again improvised modally by McGuinn on electric guitar over a bass drone.

When the two tracks were released as a single in March 1966, Columbia Records announced the invention of a new musical form called raga rock, “derived from the sitar music of Ravi Shankar.” At the press launch McGuinn brandished a sitar, even though it had not been used on either track, and the event was delayed while the band struggled to tune it backstage. A wryly skeptical report in the Village Voice made it back to Ravi in Bombay, the cutting annotated in an unknown hand, “The Raga Rock? Do you believe it?” He needed to, because in June World Pacific rush-released a cash-in album of pop covers entitled Raga Rock by a session band billed as the Folkswingers featuring Harihar Rao. Harihar guested on sitar amid a wail of fuzzbox guitars. If Ravi heard it, it is unlikely that he was impressed. The Byrds, however, were influential, David Crosby in particular. Renowned as a creative catalyst, he came to epitomize the brash, hedonistic side of the Californian counterculture. As Jackson Browne put it, “He had this legendary VW bus with a Porsche engine in it, and that summed him up—a hippie with power!” He used that power to tell his friends about Ravi’s music.

Another Californian group channeling its Indian fixation through Western instruments was the Doors. Keyboardist Ray Manzarek was, through another band, signed to World Pacific’s pop subsidiary Aura Records, and at Dick Bock’s suggestion he attended Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s transcendental meditation classes at a house in Pacific Palisades. There, in the summer of 1965, he met both Robby Krieger, who was about to join UCLA to take a course in Indian music, and drummer John Densmore. As Manzarek later wrote, “The Doors needed the other Doors. And we found each other in India.” The foursome was completed by his friend Jim Morrison. Their first demo (without Krieger) was recorded at World Pacific, and from the outset their sound was shaped by an Indian sensibility. They spent the first half of 1966 developing their repertoire in Los Angeles clubs, including the now iconic song “The End,” which was conceived as a rock version of a raga. It has a modal structure, mostly staying on one chord, starts out slow and serene, and gradually develops over eleven minutes (an unprecedented length for a rock song) to its tumultuous climax. Krieger alternates his guitar melody line with playing open-tuned strings as though they are chikari drone strings on a sitar, and there is a moment when it shifts to double time that was likewise inspired by the jhala phase of a raga. “I got the idea for that from watching Ravi,” says Krieger. “It’s not based on a specific raga, just the structure and feel.” They also worked on “Light My Fire,” which features a guitar solo modally improvised by Krieger using fingerings copied from sitar technique. This became their first massive hit.

Pop music’s Indian flowering was, if anything, thriving even more across the Atlantic. “How about a tune on the old sitar?” asked a Melody Maker headline on May 7. The new offering from the Yardbirds, “Over, Under, Sideways, Down,” had a guitar distorted to sound like a sitar—not that the effect was exactly convincing. So did the Birmingham band the Move, who were reported to be playing “Brum-raga” sitting cross-legged on the stage. Others incorporated a real sitar into their arrangements, although they tended to follow the example of “Norwegian Wood” in using it merely as a decorative element, usually replacing the role of a lead guitar. “Paint It Black” by the Rolling Stones was driven in this way by Brian Jones’s sitar riff, offsetting a drawling vocal line by Mick Jagger, whose accent, according to Melody Maker, was becoming “progressively more curried.” Jones had taken up the sitar after trying out George Harrison’s at his home. Meanwhile, Donovan had put sitars on his latest album, and a cover version of Simon and Garfunkel’s “A Most Peculiar Man” was released by Adam, Mike and Tim with sitar lines played by Big Jim Sullivan, one of Britain’s busiest session guitarists. Sullivan took sitar lessons in London from Nazir Jairazbhoy and subsequently recorded two albums of Indian-spiced pop covers. By 1968, the concept of vinaya having apparently passed him by, he had rebranded himself as Lord Sitar.

On the other side of the world in early 1966, Ravi was largely cut off from this trend. When he eventually caught up, it bemused him. Using Indian music to make pop songs, he said, was “like learning the Chinese alphabet in order to write English poems.”

* * *

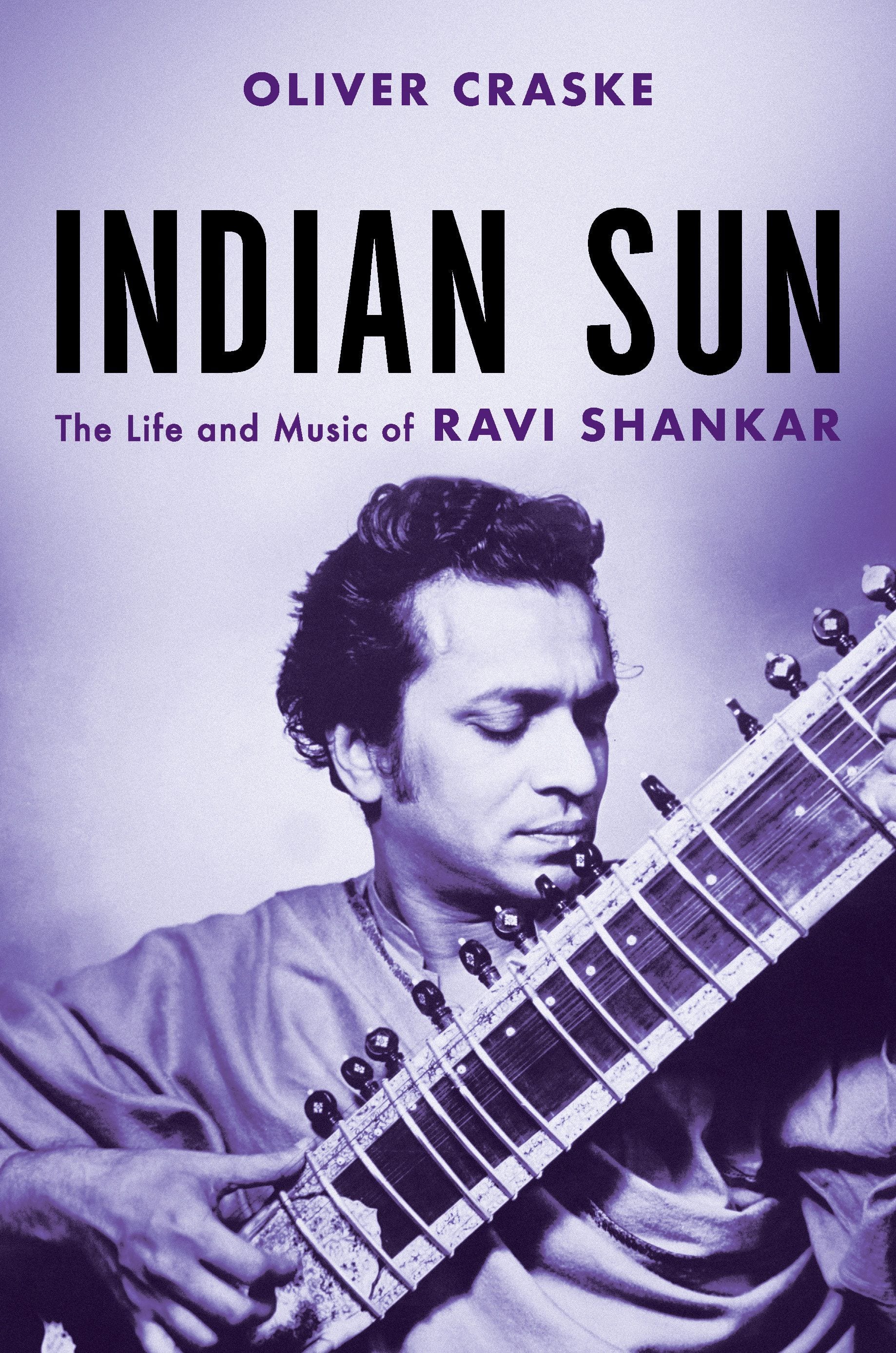

Oliver Craske is a writer, editor, and the author of Rock Faces: The World’s Top Rock’n’Roll Photographers and Their Greatest Images. He first met Shankar in 1994, worked with him on his autobiography (Raga Mala, 1997), and was encouraged by him to write his full story after his death. He lives in London.

Excerpted from Chapter 14, “The Sitar Explosion”, from Oliver Craske’s Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar (footnotes omitted). Published by Hachette Books. © 2020 Hachette Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

- Ravi Shankar obituary | Music | The Guardian

- Oliver Craske | Hachette Book Group

- Indian Sun - Oliver Craske - 9780571350858 - Allen & Unwin ...

- Rock Faces: Where Everybody is Beautiful and Nobody Grows Old ...

- Oliver Craske : NPR

- Ravi Shankar - Home

- Ravi Shankar - Wikipedia

- Indian Sun by Oliver Craske | Hachette Books

- Oliver Craske (@ocraske) | Twitter

- Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar eBook: Craske ...