In the 1970s, China faced a population crisis with potentially devastating consequences. Still years away from economic transformation, the government feared exponential population growth would result in Malthusian collapse and chaos. In possibly the most far-reaching social engineering project in human history, the Chinese government decreed each family would be allowed just one baby. Those in rural areas, where there was more need for workers, could have a second one, so long as they were born five years apart.

The One Child Policy was in effect from 1979 to 2015. In that time, families accused of breaking the policy were fined, harassed, and even had their homes demolished as a warning to others. Women underwent forced sterilizations and abortions in untold numbers.

An audience award winner at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Nanfu Wang and Zhang Lynn’s One Child Nation is one of the few serious examinations of the policy’s human costs. Because its scope is overwhelming, Wang (director of the 2016 activist documentary, Hooligan Sparrow) and Lynn start with a micro rather than macro focus. Born in a remote part of Jiangxi province in 1985, Wang was immersed in Communist Party propaganda about the policy from her childhood. She shows footage of operas, parades, TV shows, and posters (whose maniacally grinning message could be boiled down to “The One Child Policy is Great!”), pointing out herself in a chorus singing one of the painfully hectoring songs.

Having lived in America for years, Wang returns to her home village after realizing she had never truly thought about the ramifications of the policy. “Becoming a mother felt like giving birth to my memories.” In her village, she interviews everybody from relatives like her younger brother (whose existence used to embarrass her, thanks to the power of propaganda), to the old village chief about what they remember about the early days of the policy and what they did. ©

(Sundance Institute / IMDB)

As with many government-dictated mass-casualty catastrophes which use ordinary people as tools, the responses range from defensive to resignation, from uncomprehending horror to soul-scouring guilt. “Policy is policy, what could we do?” says the worried chief before his wife castigates Wang for trying to get him in trouble. Wang’s younger brother wonders whether, if he had been born a girl, he would have been “discarded” and left to die like so many others in the traditionally patriarchal society. A family planning official proclaims the policy right, calling it a “war” and insisting that otherwise, China would have “perished”.

One of the movie’s most stunning segments shows Wang’s visit to her old midwife. The serene-seeming 84-year-old woman describes in nightmarish terms the tens of thousands of sterilizations and abortions (mostly very late-term, with babies induced and then killed) she performed on unwilling women, many of whom had been kidnapped, tied up, and dragged into the clinic “like animals”. Attempting to “atone for my sins”, she now only treats infertility, showing two entire rooms in her home wreathed in banners sent by thankful couples.

Despite the stark, riveting power of its personal narrative, One Child Nation could have used more debate on whether the ends justified the means. On one side are the female babies dropped in baskets in marketplaces to die from exposure or starvation, and the forced abortions, which seem more like Handmaid’s Tale butchery than proper medical procedure. (Wang notes in an aside that the policy’s punishments feel no different than American anti-abortion laws, as both to her are about controlling women.) On the other is the argument like that proffered by Wang’s mother, who chides the filmmaker for after-the-fact moralizing, reminding her of the time’s rampant starvation and saying that unlimited births would have led to “cannibalism”.

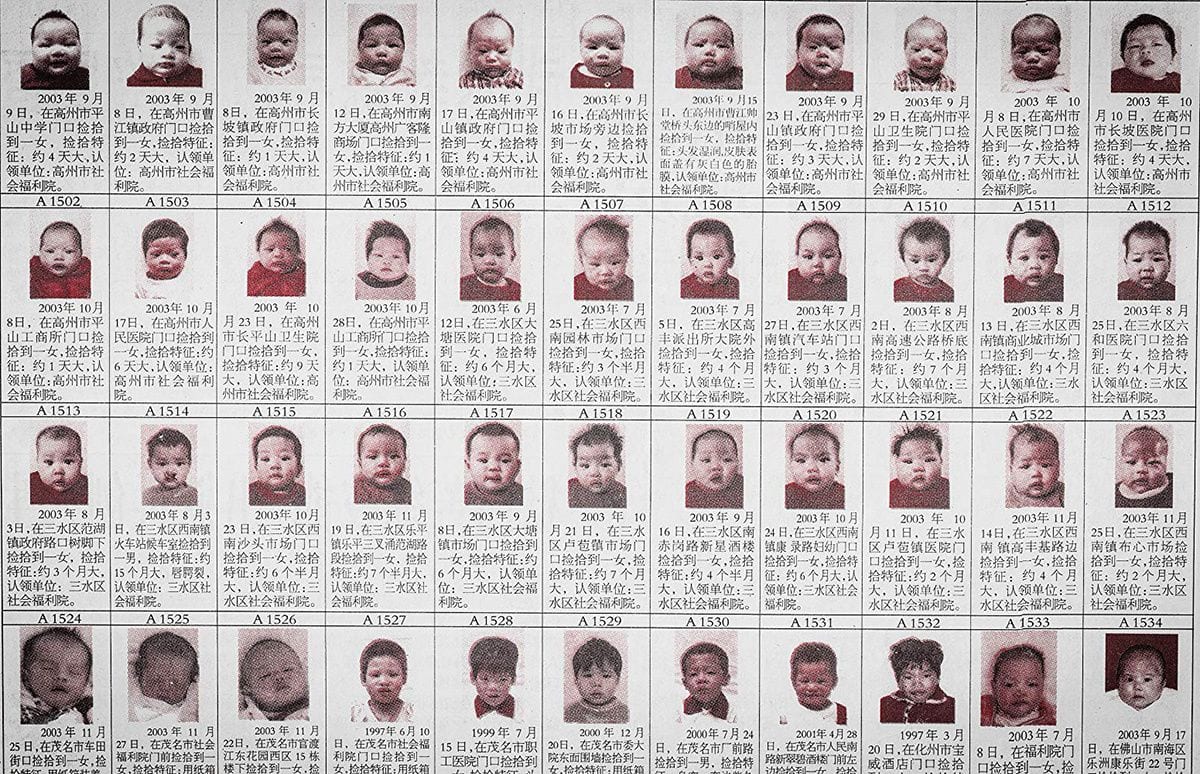

The filmmakers then turn the corner and discover another side to the story, one that has only rarely been told, and even then has led to censorship and threats. She discovers stories of an underground network that trafficked unwanted babies to orphanages. Many of those babies ended up being adopted by Western countries. Although at first this appears to be a win-win solution to the problem of excess births, Wang and Lynn discover that there is a far uglier, seamier side to it that is both shocking in its ugliness and yet utterly unsurprising for anyone even remotely acquainted with the corruption endemic to modern-day China.

Quiet and spare, One Child Nation is a brutal story, made more bloodcurdling—like so many documents of 20th-21st century atrocities—by the seeming nonchalance with which it is told.