Heavily treading the line between childishly playful and bizarrely ambitious, just months ago, Daniel Lopatin, aka Oneohtrix Point Never, delivered Age Of, his 10th and most “accessible” album to date. In his world of recondite, contemplative, and always utterly challenging electronic soundscaping, “accessible” primarily refers to his newly found penchant for collaborating with alternative music giants, such as James Blake, who co-produced and mixed the album, and ANOHNI, whose debut solo album, 2016’s Hopelessness, he helped produce. One could also mention the number of vocals, often delivered by Lopatin himself, found on this album, and also many songs’ clear, relatively coherent structure, a concept also new to the experimental music ingenue.

This trajectory from almost inconceivably abstract toward the perceptible has seen Lopatin develop a penchant for knowable narratives. Over the past two years alone he added David Byrne and FKA Twigs to his list of associated acts, released a song he initially wrote as a demo for Usher (Age Of‘s “The Station”), delivered another tune that was “meant for Pixar” (“Toys 2” is the name, naturally), and won the Soundtrack Award at Cannes for his first fully cinematic delivery, the music for the Safdie brothers’ revered arthouse film Good Time.

Now, possibly on the precipice of transitioning from electronic visionary into a household name, Lopatin, at 35, is embracing the possibilities. Even with added structure, Age Of is in many respects his most wide-ranging record, an all-but-impossible-to-describe concoction, combining everything from inarticulate screams of Prurient (noise artist Dominick Fernow) and Anohni’s hankering howls, upright bass distortions, digitalized organ loops, fuzzy jazz backdrops, flickering and echoing synthesizers, the timbre of an obscure electric wooden experimental instrument called a daxophone, and plenty of harpsichord, which is the album’s prevalent weapon of choice.

Despite the mostly straightforward melodic exposition, songs still end abruptly or ascend to an amalgam of overlapping sounds, unbearably tensely woven but only very loosely hanging together. All this, certainly, comes by design – Lopatin, who is in the process of creating a manifesto for an artistic approach he calls “Compressionism” (“It’s dealing with the overload of knowing about too much stuff, about being exposed to too many historical inputs, and then turning it into some kind of coherent jumble,” he said in an interview for the New York Times), is also in the process of recreating the entirety of human history, as seen through the eyes of a distant civilization coming in contact with it for the first time.

His fascination with the ephemeral and the universal in human nature is evident at every turn on Age Of, for which he chose a peculiar cover — a painting of three Stepford-esque, mid-20th century women staring in ecstasy at a MacBook, which reveals itself to them by opening up, its monitor producing intense glow. The artwork is a painting by Jim Shaw, called The Great Whatsit (2017), and Lopatin admittedly instantly saw a connection between Shaw’s approach to seemingly timeless human fixations, and his own compression of all of human history in some 75 minutes, the length of his MYRIAD live performances.

“It’s the sort of grandeur of staring into nothingness at a lack that needs to be filled, a fundamental desire for an answer… Jim swaps in a MacBook for what could have been some other object 10 or 20 years ago. It could be anything, and it would still glow,” said Lopatin in an interview for Art News. However, Shaw’s painting is but the tip of a fast-melting iceberg for Lopatin. In order to complete his latest expression, he devised MYRIAD, a live performance of (mostly) Age Of, in which he assembles the pieces from the album so as to accompany what he calls the four epochs of human civilization: the Age of Ecco, the Age of Harvest, the Age of Excess, and the Age of Bondage.

The images accompanying the epochs on the promotional materials for MYRIAD look like early Andersen fable illustrations, another dive into the historic(al) for Lopatin, who tries to chew on the notion of history itself in his dozen-or-so “concertscape” live MYRIAD performances in 2018. In Lopatin’s words, the idea for MYRIAD came from watching 2001: A Space Odyssey, his favorite film; however, in MYRIAD, instead of aliens prompting the apes to evolve, he imagines a post-civilization, barren universe, inhabited by nothing but advanced artificial intelligence exploring what human history was about and learning all the information from “our total sum output of everything we ever put on the Internet”, said Lopatin in an interview with the Red Bull Music Academy, the main logistical sponsors of the MYRIAD tour.

It is an utterly bleak scenario, but a compelling artistic theme nevertheless — imagining all of humanity from beyond the event horizon, beyond all of human history. With this in mind, however abstract, the epoch make sense. By acknowledging them Lopatin investigates the human condition as a historical whole, from its primordial days of unison with the nature, all the way to the cataclysm, caused by what he believes is the insatiable need for fascination, consumption, excess, and waste. The Age of Excess is often equated with capitalism in his interviews, though it would be a mistake to perceive this work as political — rather, it is a philosophical rumination on the very meaning of existence and the way history is formed, the way narratives emerge and what they may mean for different entities (in this case literally as OPN takes the perspective of an intelligent and non-human machine).

For the MYRIAD tour, Lopatin directs a band of live musicians for the first time. His small ensemble is brought to life by the Brooklyn minimalist composer and piano virtuoso Kelly Moran, multimedia and acoustic artist Eli Keszler, and keyboardist Aaron David Ross. As a quartet of musicians whose scope of expertise stretches well beyond soundscaping, these extraordinary artists imbue MYRIAD with organic livelihood and coherence it may not have were it not for their understanding of the magnitude of the idea. MYRIAD tour, consisting of merely 14 dates, kicked off in the New York Park Avenue Armory, in partnership with the ever-innovative Red Bull Music Academy. The venues it has graced are emblematic: the Barbican London, the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Montreal’s Monument-National, the Cent Quatre in Paris, and London again at he Roundhouse, are some of the places Lopatin took, or will take his shows, to.

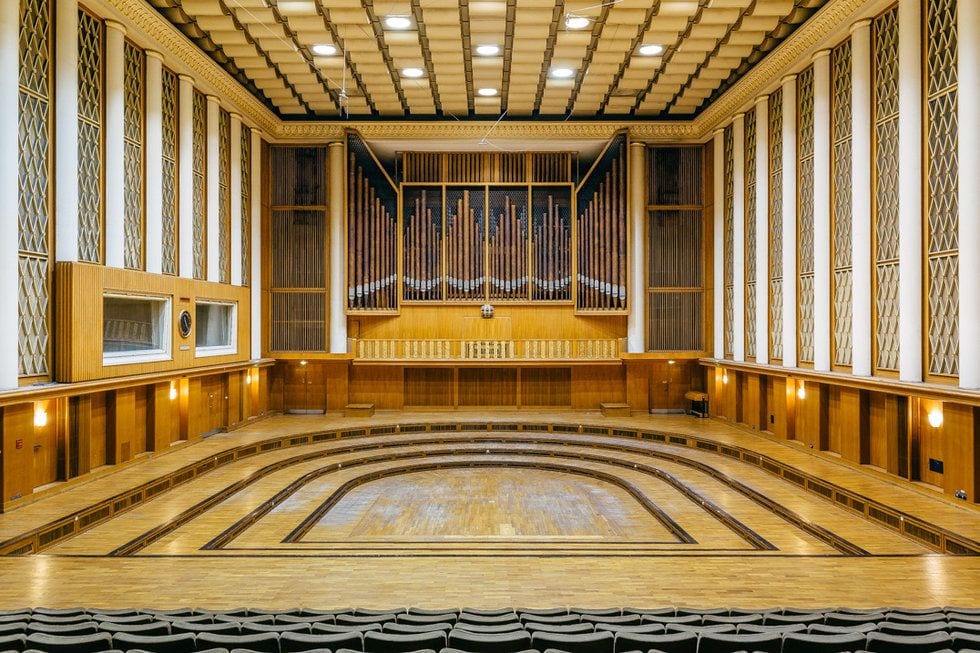

On this list, Berlin is no exception. On September 20, MYRIAD was made part of the month-long Red Bull Music Festival, held in the iconic Funkhaus. Designed by the famed German Bauhaus architect Franz Ehrlich, what had been a vacant building complex of a defunct plywood factory, turned into East Berlin’s prime location for the GDR radio transmissions and broadcasting in the 1951 (and kept its function until the unification of Germany). Acoustically impeccable and architecturally formidable, today Funkhaus is world’s largest connected studio complex, overflowing with historical curiosities, peculiar narratives begging to be told after a single glance at this glorious monument. One of the stories concerns Ehrlich – it is said he used the deep red limestone from the demolished Reich Chancellery to build the floors. On what would be the second-to-last warm evening in Berlin in 2018, hundreds of people huddle to smoke and chug a quick drink outside the entrance to the Great Recording Room 1, the trapezoidal auditorium with a gigantic concert organ towering above the “tub”, a U-shaped cascade construction allowing the musicians to be surrounded by the audience. The room itself has 250 seats, but many more rush to sit everywhere on the hardwood floors around the tub, and the hall looks like it’s swarming.

The room itself is astonishing, soundproof, and foolproof in every aspect. The 40-foot ceilings feature plywood cladding and half-columns coming in dozens, shades of goldenrod yellow wood dominating this vast space made up entirely of repetitive patterns adding to the symmetry. The walls are also covered in wood and stucco ornaments for ideal sound absorption; top to bottom arrays of pristine, identical white pillars are separated by webs of metal mesh. Inside the walls, woven horse hair and Stasi wire taps (located behind every clock in the complex, the large black timekeeper on the left side of this hall included) can be found. Yellow, grey and lush, dense brown are the only colors perceptible, their interplay forming an austere, authoritative setting . The intricate and unbearably symmetrical cladding of every part of the studio elicits varied emotions, among them the intense fear of being trapped inside, the walls closing in while you are breathless in awe.

Similar things could be said about Lopatin’s MYRIAD performance — no surprise he chose this venue. By the time his quartet is one stage with their, well, myriad instruments, the room has turned deep blue. Two drooping, amorphous sculptures hang from the ceiling, the works of Nate Boyce, a collaborator of Lopatin’s who also delivered the blinking visual collages accompanying the show on the two giant screens behind the band. Beside those two visual elements, everything else is pure acoustics; the dancers from “Black Snow” or the black blob seen at the Armory, are omitted from this show, largely due to a lack of space (those sitting closest to the performers were less than 10 feet away). Without much ado, Moran launches her vivid harpsichord, deliberately fully Baroque in melodic structure, and Lopatin brings the sublime futuristic noise, juxtaposing the palpably historical with his abstract ruminations on the end of history as such. The sounds soar and echo over a dozen or so speakers positioned with precision across the venue, so as to offer the kind of aural experience which truly is indescribable.

The songs off Age Of, gilded by Kezsler’s feverish experiments with wooden percussions and some keyboard improvisation from Moran and Lopatin, should sound familiar but the opposite is true. Even with the album released months ago and (however vague) in-depth explanations about what the “concertscape” is about, even with the deliberate use of classical instruments and heavy reliance on the derivatives of Bach’s work on harpsichord, MYRIAD is a completely alien experience. Despite much of the music germinating from the works of Max Richter, Bjork, Peter Gabriel and Brian Eno, all the purposefully recognizable elements are there mostly to trick you into trying to label what you’re hearing. All of the music presented over the 75 minutes of extended Age of tunes and specks of carefully curated content from Lopatin’s back catalogue (R Plus Seven, for example) is too expansive to be minimalistic, too aggressive to be ambient, too structured (indeed) to be experimental, and certainly too erratic to be simply “electronic”.

This lack of coherence, if not of structure, is most likely Lopatin’s bottom line — once history physically ends, all that is left is speculation. Everything is familiar yet distant, and whoever gets to interpret what is left of a civilization, will be creating an impression of this history on their own. Historiographer Keith Jenkins’ has called history itself “promiscuous” and subject to any interpreter’s own impressions and beliefs. And this is exactly what Lopatin’s band delivers with MYRIAD – a vast sonic journey familiar only insofar that it is a simulacrum of a civilization on the precipice of universal doom (or the fourth epoch, in his mind), an experience anyone could interpret however they wish, so long as they understand they are merely scratching the surface. Despite great musical prowess and melodies pleasant and structured enough to seduce anyone, there is no “product” here, no real “message” to be taken and dissected.

The challenges that come with this high end concept are many, and they are here by design — it is often argued that Lopatin sees history as a sequence of separate events merging in a “funnel”, collected and disseminated by the Internet, or a cyclical concept in which humanity repeats its mistakes until it becomes extinct. “Retrofuturism” is a word often thrown around and misused, and while it does come to mind, it would be reductive to describe MYRIAD’s sound that way. If anything, it feels as if Lopatin is trying to challenge the notion of history being either finitely sequential or infinitely definably cyclical; his melodies compress the whole of human condition in a single continuum, in which all of existence is undisputedly part of the same experience, regardless of the perspective.

All these ideas leave plenty to absorb, and the band doesn’t shy away from continuously daring you to do so, be it through classical harpsichord arrangements, designed to evoke sentimentality, or extended sampled timbres rippling for what seems like ages without ever really taking off, maintaining the state of plateau which slyly induces discomfort. In terms of the music itself, Lopatin’s vision has long been beyond the binary “good” or “bad” music labeling, but here he at his best when he’s at his most structured. “We’ll Take It” and “Black Snow” may be the closest he has ever come to a traditional song layout, but these tunes, both lyrically and melodically, convey messages which could otherwise be lost in the more abstract melodies, many of which are slightly improvised live.

Given how much effort he has invested in this celebration of epistemological skepticism, it’s good to have a fallback, a shortcut of sorts, if you happen not to be in the mood to think too much. Otherwise, all 75 minutes are airtight and the decision to not make the show longer than that is a welcome one. If you follow the rabbit hole and try to devise a narrative from the angelic sounds and frequently demonic, disturbing imagery that accompanies it, you may find yourself gasping halfway through.

It is genuinely strange to witness a tightly woven performance in which barely a toehold is offered to anyone seeking to be guided toward a meaning, inside or outside the sound but this is precisely what Lopatin aims for — and his band, their vision, pulls it off. Their insistence on audience’s deepest introspection is all but unbearable, and the experience is knowingly unpleasant at times, but chances are you will leave the venue deeply moved, possibly with a fresh perspective on life itself, which is the rarest of artistic commodities nowadays. But Lopatin knows that already, too. He just doesn’t want to make it too obvious.