A flock of owls perch on a telephone wire, around the corner from a humming UFO that has just touched down in a small desert town and beckons you aboard. A single white owl appears in the dreams of alien abductees at 3:33 a.m. It’s a brown owl that turns out not to be any kind of extraterrestrial emissary at all, simply an illusion created by a tree branch.

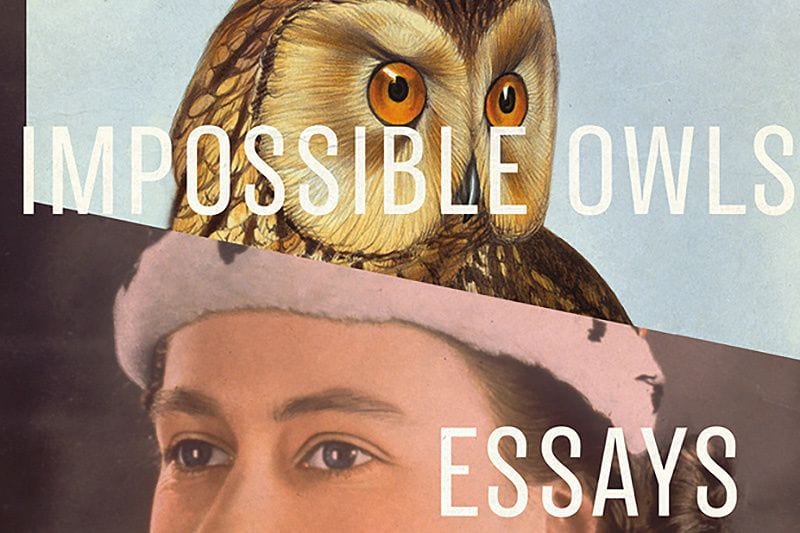

These are just some of the wise avians encountered in Impossible Owls, the debut essay collection from former Grantland and MTV News contributor Brian Phillips. Phillips’ book rises from the rubble of those two outlets—Grantland, which was known for its longreads, folded in 2015, and in 2017, MTV News scaled back its online presence following a short-lived rebrand—and carries forward their spirit of enthralling nonfiction. The scope of Impossible Owls is broad: its eight essays run the long-form gamut from sports writing to travel narrative, pop culture criticism, and memoir. What holds these styles together is Phillips’s smart, readable prose as well his obsession with all things alien—the foreign, the puzzling, and the paranormal.

As the title suggests, the owl is an important creature for Phillips, although the owls he encounters on his travels and in his research are never quite real owls. Rather, they are hallucinated, misremembered, and, more than once, aliens in disguise. “The more real an owl appears, perhaps, the less likely it is to be what it seems,” he writes in “Lost Highway”, an essay about (among other topics) alien abductees living alongside the forgotten parts of Route 66, one of whom is convinced that owls are not of this world (116).

This negative correlation between seeming and being fascinates Phillips, and he finds it permeating our strangest myths, be they conspiracy theories (the underground ziggurat in Alaska that could power half of North America must exist — otherwise why would the government cover up all traces of it?) or the rules of etiquette (the real power of the British Crown, he argues, arises from a calculated balance between shows of restraint and shows of extravagance). But Phillips is no staunch empiricist, nor does he want to shatter delusions or expose machinations. He is content to remain in a wide-eyed and owl-ier place.

Throughout Impossible Owls, Phillips lets not only owls but all sorts of fauna take the lead and guide him to geographic and intellectual limits. It’s as if, faced with a glut of possible subjects, he has decided simply to go where the animals are. There’s the goldfish in a bag that sums up what it feels like to be 17 years old; the tiger in an Indian preserve obscured like the Mona Lisa by throngs of tourists and their flashing cameras; and the watchful vultures in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that kick off a rumination on small-town paranoia.

In the opening essay, “Out in the Great Alone”, Phillips quite literally follows teams of dogs across the Alaskan tundra while covering the Iditarod, a thousand-mile-long dog-sled race held each March under the most grueling weather conditions. He keeps pace with the “mushers” from above, in a rickety bush plane, which, he stresses, is often a more dangerous place to be than on the ground. What starts off as a niche sports piece becomes a lengthy profile of humanity in extremis, and not so much the humanity of the racers, but that of the people who inhabit the remote villages that serve as checkpoints. Phillips meets many Alaskans there who all share an awe at what he calls the “vast and terrifying cosmos of personhood”, a heightened awareness about the uniqueness of simply being a person, brought on by living in a place where there are so few (30).

Despite the many animals sighted and remote areas traversed, these essays are not about the wild; on the contrary, they’re very much about people, and sometimes about a specific person — Phillips himself.There’s a Gonzo ambition underlying Impossible Owls: more than once, Phillips risks life and limb to bring us reports from the edge of civilization. The book has been marketed as a kind of Pulphead of the new media age, and it’s true that Phillips shares some qualities with essayist John Jeremiah Sullivan — specifically, an approach to journalism that emphasizes the writer’s prowess. However, since Pulphead appeared in 2011, a slew of essay collections by writers like Rebecca Solnit, Roxane Gay, and Samantha Irby have made space for a different kind of personal writing that more often exists online instead of in mythic dude magazines like GQ. This stylistic shift and increased participation by women may be what differentiates the print and internet eras as much as anything else.

At times, Phillips reaches for the baton of new journalism, and at others, he steps back, sensitive to the changing context. And then there are times when both impulses unwittingly and unfortunately collide, as in the penultimate essay, “Once and Future Queen”, in which Phillips unpacks all kinds of symbolic heaviness in Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton’s body language during her visit to the Yukon territory. The intention is good: he wants to see past the breathless press coverage and consider the experiences of royal women within a more relatable continuity of womanhood or even personhood. But there’s a Jamesian gaziness in stylishly plumbing the psyches of aristocratic women, and the piece reads as though queendom were another frontier for Phillips.

Phillips is at his best when his need to parachute into exotic environments doesn’t get in the way of the empathy and patience that his essays otherwise model. Over the course of Impossible Owls, it becomes clear that there’s a difference between hunting for aliens and acknowledging that they might exist and that you can’t know for sure. More often than not, Phillips makes a case for the latter—for an awed agnosticism that can seem out of step in a world where so many people search doggedly for unique and uncanny subjects to claim as their own. But there are times when he joins the hunt, in spite of himself. After all, the owl is a bird of prey.