Paco Ignacio Taibo II has been called Mexico’s “de facto minister of culture”. A literary icon with over 80 books to his name, he was recently appointed director of the Mexican government’s national publishing house, Fondo de Cultura Economica – a move which has been described as akin to “a somewhat younger Noam Chomsky being appointed US Secretary of State.”

Five decades ago, in 1968, he was cowering in a tiny room with a poster of Tokyo’s Ginza district on the wall, unable to sleep for fear the Mexican army would burst into the house and arrest him. His fears were shared by hundreds of thousands of other Mexican students – the ones who hadn’t already been arrested or murdered by the army, that is. In the wake of a tremendous 123-day long student protest movement for democratic reforms, crushed only by the gunfire of Mexican soldiers and the arrest and torture of thousands of activists, Taibo was fortunate to have miraculously avoided either fate.

Yet survivor-guilt haunted him (as it did so many others of his generation). He struggled to return to classes, and after getting in a fight with a professor who made fun of the student movement, he dropped out. He wrestled for years with what sounds like a form of PTSD from the experience. Eventually he rebuilt a life as one of Mexico’s most renowned writers and cultural doyens, culminating in his latest appointment by a reformist government that is in many ways the inheritors of 1968’s legacy.

Water drop by qimono (Pixabay License / Pixabay

His classic account of the student movement of 1968 – ’68, originally published in 1991, with English translation by Donald Nicholson-Smith in 2004 – has now received a timely reissue, with an updated author’s note contextualizing this important book in the wake of Mexico’s latest political upheaval.

Taibo has struggled with this subject matter before. In 1982 he published a strange yet poignant book titled Calling All Heroes: A Manual for Taking Power. Its subject was also the student movement of 1968, but he approaches it obliquely, with a strong dose of the fantastical and magical realism.

Its protagonist is a crime reporter who, pursuing a murderer while the political turmoil of ’68 rages around him, is surprised when his target turns around and stabs him; he spends months recovering in hospital. In this loose allegory for the experience of embattled students, the narrator drifts in and out of consciousness, summoning an army of superheroes – Sherlock Holmes, Wyatt Earp, The Three Musketeers, and others – to confront the tyrannical Mexican state and use their powers to free its people.

The Shifting Tides of Memory

Calling All Heroes revealed a lot about Taibo’s struggle to come to terms with the student movement’s apparent defeat in ’68. In it, there is a dialogue between the narrator of the tale and Taibo himself. Taibo writes to the narrator about his inability to write about the events of ’68 – “All material that goes into literature should be allowed to cool. I have never been able to write while stories were still hot. One has to let the bonfire go out before walking on the ashes… I don’t believe I’ll ever write about the past year.”

Yet he did eventually produce just such a book. ’68 is a powerful paean to the student movement, a breathless first-person account of the movement as he experienced it.

A central theme of Calling All Heroes is the blurry line between fact and fantasy; memory and imagination. The story weaves together real events from that tumultuous year with others imagined by its feverish protagonist. In ’68, Taibo tackles the shifting nature of memory in more straightforward fashion. He opens the book talking about his inability to forget what happened that year, and the ways in which the experience was burned into his consciousness. His account resonates with anyone who has been part of history’s powerful moments, and who knows how deeply formative these moments can be, haunting participants for the rest of their lives:

“Damn it, almost fifty years have gone by and I have a much clearer recollection of the debates over whether the silent march should indeed be silent, the meetings in the Mixcoac market, and the nights lulled to sleep by the two mimeograph machines we had at Political Sciences than of whatever happened in my life a month ago.”

The narrative power of ’68 belies the fear he expressed in his previous book that the memories were fading. Far from it – here he recalls images, moments, scents and feelings with an immediacy that is dulled in no way by the passage of 50 years.

The Movement

Taibo’s account in ’68 is fast-paced, breathless, and inspiring. Unlike the fantastical Calling All Heroes, ’68 is a more straight-forward first-person narrative history of the movement, from Taibo’s perspective as a participant. He’s achieved a rousing success, evoking the spirit of a movement and the sense of what it was like to be part of the fast-paced process of changing history.

He describes the movement with love and respect, honest about its warts and failings but loving them too. Events moved so quickly over those 123 days that there often wasn’t time to do things right or think things through; actions counted louder than words, and often serious mistakes were made. But these were taken in stride; the students learned, adapted, and propelled their movement continuously forward.

“The Movement was, in fact, many things at once. For thousands of students, it meant an unmasking of the Mexican state as an emperor with no clothes. It meant the occupation of schools and the creation of libertarian common spaces based on assemblies. It meant family discussions in thousands of homes. It meant crisis for the traditional ways of misinforming the nation, a confrontation with leafleting, with the live voice, and with the rescuing power of rumor as alternatives to a controlled press and television. It also meant violence, repression, fear, prison, assassination. But above all, far more than anything else, it meant the reengagement of a generation of students with their own society, their investment in neighborhoods hitherto unknown to them, discussions on the bus, a breaking-down of barriers, the discovery of solidarity among the people, and, as they made it past the gray perimeter of the factories and reached those who were to be found within, the closest encounter yet with a mass of ‘others.'”

This point Taibo returns to repeatedly. One of the things the Movement taught to him and others was that as students they were but part of a vast nation, and for the first time they began to see that nation for what it was, and to see themselves as part of it. It was working-class factory employees; it was poor Indigenous women in the marketplace; it was rowdy technical school students who preferred films and tequila to political discussions.

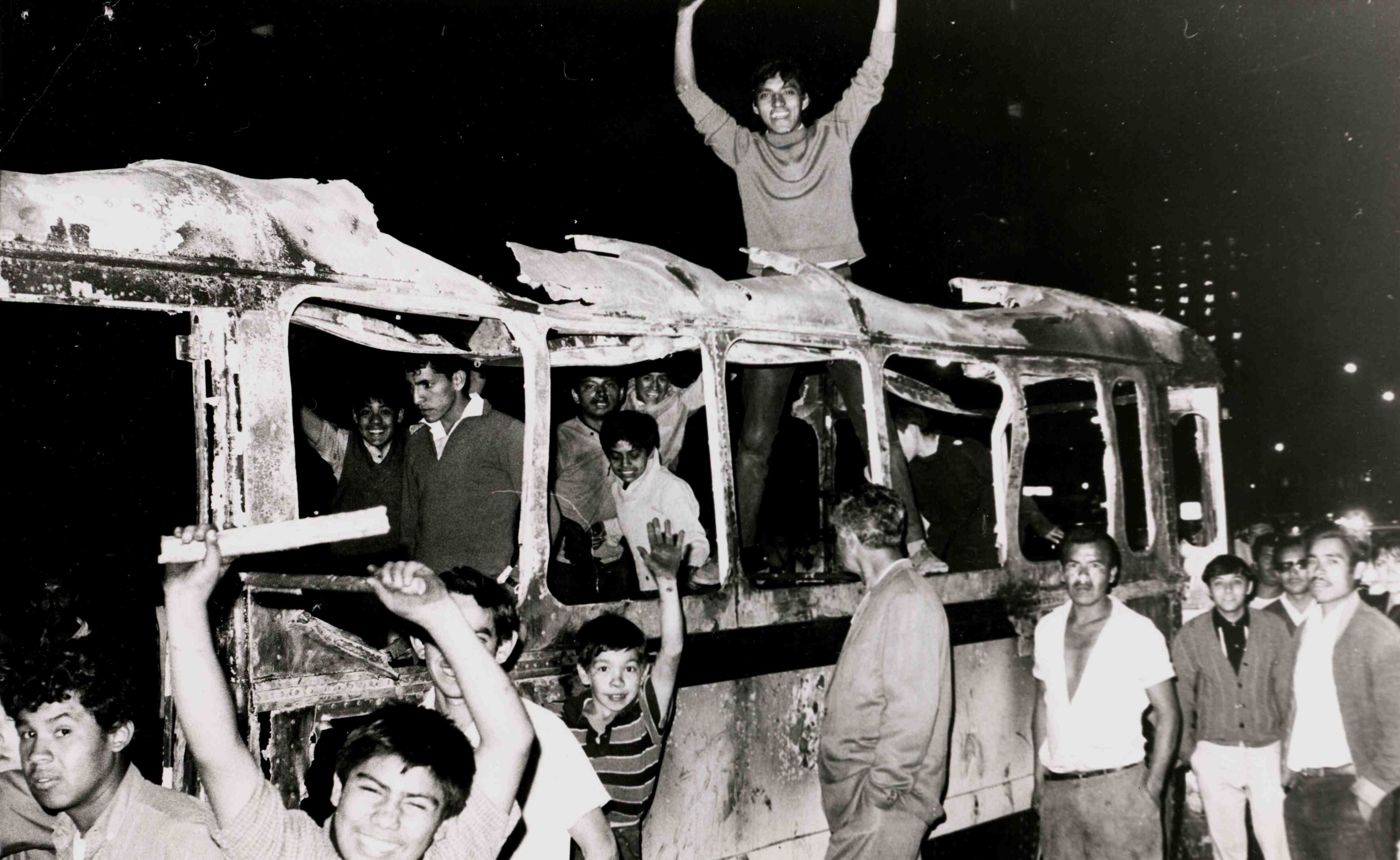

Students in a burned bus. 28 July 1968. Photo by Marcel·lí Perelló – my personal archive, Public Domain. Wikipedia.

The student movement could propel mass rallies of tens, even hundreds of thousands onto the streets, but they all knew it would require connecting with that other Mexican nation in order to achieve whatever amorphous, uncertain victory they were aiming toward. They sought to branch out, sending propaganda teams to meet with workers and trade unions and proselytize in the factories.

Taibo recounts these adventures with a combination of deep, passionate respect for what they did, coupled with the wry sarcasm born of years of hindsight and wisdom. In the factories and working-class neighbourhoods, he recalls, “we were strange birds who showed up, then took off after showering the factory with unreadable pamphlets that the employees of the Azcapotzalco refinery or the workers at the Vallejo or Xalostoc plants would later use for ass wipes.”

There’s a profound innocence to the idealist strikers, recalled with pristine clarity by Taibo decades later.

“What was going on? For those of us who had got our politics out of books, political reality was a completely new school. All we knew was that there was a Movement and that it had to be defended against those who sought to destroy it with clubs and bazooka fire, and protected from those who wanted to suffocate it with words, slow it down, and halt it.”

Toward the end of the movement’s 123 days, they finally began to connect with that greater Mexican nation. In fits and starts, small bands of workers and delegations from trade unions began to meet with the students and show up at rallies. They were on the cusp of that breakthrough, he feels, and perhaps that’s what drove the government to inflict its final, desperate, murderous strike against the movement.

The Tlatelolco Massacre

The slaughter of students and other civilian protesters at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Mexico City neighbourhood of Tlatelolco has been written about extensively. In brief, a government scheme saw police provocateurs disguised as students open fire – after a pre-arranged signal from the military — during the rally on 2 October 1968. In response, the military opened fire on the crowd of 10,000 and killed an indeterminate number of people. Eyewitnesses say deaths were in the hundreds; authorities were later accused of hiding and destroying bodies.

This was the bloodiest single day of repression during the student strike, but it wasn’t the only one. Students were arrested, tortured, and killed throughout the duration of the strike. To be on the streets was to constantly be at risk of getting picked up by a van of undercover police, Taibo writes. During one fierce 12-hour battle that ensued when Mexican troops tried to storm one of the campuses, dozens of students were killed while resisting the more heavily armed soldiers. In a poignant image, Taibo recalls a friend of his leaping on top of a tank and pummeling it with an iron pipe.

“I wanted to capture the moment in a poem but could not,” writes Taibo in ’68. Yet in a way he has – the narrative of ’68 has a truly epic, poetic quality to it, carried along almost lyrically in vivid imagery and stirring metaphor.

“Where Were You?” The Guilt of Survivors

A central element of both ’68 and Calling All Heroes is survivor-guilt. Taibo hammers it home in Calling All Heroes, emphasizing the suffering that came from having lived through the revolutionary hopes of ’68, only to have them dashed and then have to live on through the years of shattered dreams which followed. Whatever the fears and stresses of the fraught struggle, dodging plain-clothed police squads and defending campuses with stones and clubs against state troops armed with bazookas, the true suffering for many came from living on in the wake of defeat.

“I know several people who spent ’69 in sleeplessness,” Taibo writes to his narrator in Calling All Heroes. “I believe I was one of those who allowed anguish to follow them and change them…it was ’68 that changed me, but I changed in ’69. I became disagreeable. I became more calculating in emotional things. I learned to be afraid of emotions. You also withdrew inside yourself, as if by building a shell you could preserve the valor of ’68, which threatened to escape from our bodies.”

That is the grim, hopeless mood of the survivors in Calling All Heroes. Its protagonist deals with his crisis by re-imagining the struggle; by conjuring up an army of fictional superheroes to do the work the student movement could not, and to defeat once and for all the corrupt forces of the state. When he tells them about the impending arrival of his army of superheroes, the narrator’s friends express the skepticism of ruined idealists: “Are there really any heroes left?”

The narrator of that book, recovering in hospital after having been in a coma for a lengthy period of time, requests accounts from his friends to fill in historical gaps. These too are full of bitterness: “We got together Saturday after Saturday to see if it still felt the same as it had during the Movement,” writes one. “And even though it didn’t, we did it again every other week to say it had all been a mistake and that the parties, even with the familiar faces there, weren’t worth a nickel compared to a meeting, a brigade day, and those gatherings.”

Another writes him about how she can no longer bear the city – “how beautiful it had been in ’68 and how shitty the streets and the people and the city were in ’69…Honestly, we might have been better off falling to the ground.”

In ’68, Taibo finds a different form of solace in the march of history. He and other veterans of ‘the Movement’ finally achieved some degree of vindication with the 2018 landslide victory of left-leaning presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). This crushed the mainstream parties, including the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) .which had held power autocratically since the Mexican Revolution. ’68 was actually first published in Spanish in 1991 – as the PRI still held power – but in a sense the book’s publication marked the beginning of a renewed civic mobilization which was to eventually dislodge the PRI and lead to the landmark events of 2018.

Photo by PixelAnarchy (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

The Movement Carries On

’68’s epilogues also carry a riveting and inspiring story. The first one, written in 1993, outlines the fascinating process by which veterans of the ’68 movement came together 25 years later to reconnect and remember. What emerged from this was a reignited movement, of a sort – the now well-connected and well-established survivors (like Taibo himself) organized and began pushing for an official inquiry into the events of ’68. They secured felease of government archives and documents that would reveal indisputably what had happened and by whom, and official assignment of responsibility.

A Truth Commission was struck, and the battle was rejoined, with right-wingers and government functionaries trying to slander the activists past and present. The inquiry assumed a catalytic role in generating a renewed demand for democratic reforms. Veterans of ’68, now with families and children, took to the streets once more.

This lengthy epilogue makes some important points about the historicization of the movement, which Taibo observes has assumed mythic proportions. But what’s wrong with that? “[A] myth is not necessarily a lie,” he writes. “[G]enerally speaking, the myth is the rumor-borne truth of those that got screwed (after all, the victors control national television).”

In fact, he points out, for the democratic struggles which continue today, what is needed is not demythification, but remythification. He rejects the sober skepticism of “objectivity hounds”, observing that these myths “have energized thousands of Mexicans in their ongoing struggle for full democratic rights. I am thus in favor of the fantasy, the antiauthoritarian myth of the Movement, along with the accompanying bloody-mindedness with which that Movement fought for democracy. I am in favor of saying it yet again: It is not over yet. As for objectivity, I don’t give a royal shit about objectivity. Because, when you get down to it, this is a myth that gives them a major pain in the ass.”

A second epilogue, added in 2003, picks up the tale, relating how the long-dominant and repressive PRI party was finally defeated in the polls in 2000, and how the facts that have emerged since have revealed incontrovertibly the government’s role in the Tlatelolco massacre. For the latest edition of this slim, powerful book, Taibo added a further author’s note in 2018, recounting the “electoral revolution of July 2018” that brought President Obrador to office, and which he hopes “will open a great door between past and present.”

“I have walked recently through the city streets, no longer a dinosaur witnessing the terminal spectacle of our extinction as a generation: instead, this is a reunion.”

Reading ’68, one cannot help but think of the ongoing protests in Hong Kong – a world away and a culture apart, yet a very similar ethos resonates. The Mexican student protests had no real central leadership; a very loose and organic notion of what their demands were – ‘democratic reform’ – obfuscating attempts by the authorities and government to bribe or buy out its non-existent leaders. No matter how the state attempted to counter or malign the protestors, they bounced back resiliently, coming together in ever larger rallies and marches despite all the state’s usual tactics. No matter how often the state flexed its muscles, and how hopeless things looked, the students continued to vote in favour of continuing their movement.

It took unprecedented slaughter and repression to finally crush the movement; one can only hope that a similar fate will not ensue in Hong Kong. Whatever happens, there is a potent lesson in ’68 and the context in which it re-emerges today. Even brutal repression cannot stamp out rebellion and change forever; and the ghosts of a movement often return to finish the work they started when their opponents least expect it, underscoring the inevitability of change. Even if it takes decades to bring it about.

As Taibo reminds us about the great and perhaps never-ending struggle for liberty and against tyranny, and as evidenced so clearly in the student movement of ’68: “Every time someone declares it forgotten, transcended, resolved, or dead and buried, it comes back.”

Photo of Paco Ignacio Taibo II: FotosEspecial (Courtesy of Seven Stories Press)

Sources Cited

Cooper, Marc. “Paco Taibo’s Republic of Readers” The Nation. 15 April 2019

Nelsson, Richard. “How the Guardian reported Mexico City’s Tlatelolco massacre of 1968“. The Guardian. 11 November 2015.

Taibo II, Paco Ignacio. ‘68: The Mexican Autumn of the Tlatelolco Massacre. Seven Stories Press. October 2019.

Taibo II, Paco Ignacio. Calling All Heroes: A Manual for Taking Power. PM Press. Paperback. 2010.

- '68 by Paco Ignacio Taibo, II - Penguin Books Australia

- by Paco Ignacio Taibo

- '68 by Paco Ignacio Taibo, II: 9781609808495 ...

- '68 by Paco Ignacio Taibo II: 9781583226087 ...

- '68: Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Donald Nicholson-Smith ...

- Paco Ignacio Taibo II - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

- Paco Ignacio Taibo II | Cinco Puntos Press | Independent Book ...

- Paco Ignacio Taibo II — Restless Books

- Paco Ignacio Taibo II - Wikipedia