On the day Alex (Gabe Nevins) first went to Paranoid Park, a skaters’ hangout in Portland, he worried that he wasn’t ready. His best friend Jared (Jake Miller), Alex recalls, “laughed and said, ‘Nobody’s ever ready for Paranoid Park.'” It’s a caution Alex writes down in his notebook but cannot heed. He’s drawn to the Park, which he describes with a tinge of rapture: “One appeal of a place like Paranoid is the kids that skated there,” he says as the camera shows boy after boy completing the same airborne maneuver. “They’d built the Park illegally, all by themselves. Train hoppers, guitar punks, skate drunks, throwaway kids. No matter how bad your family life was, these guys had it much worse.”

Alex knows something about a bad “family life.” At the start of Gus Van Sant’s lovely, darkly evocative Paranoid Park, his parents are separating, still angry enough that they’re disinclined either to maintain a united front or pay much attention to Alex and his little brother Henry (Dillon Hines). A bright, restless, vaguely disillusioned high-school junior, Alex seeks community and identity among the skaters, skilled and self-assured, “throwaway” but possessed of a beguiling grace.

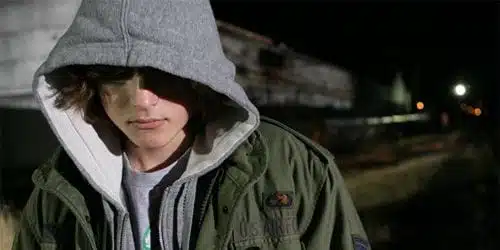

Alex’s fascination with the skaters provides the movie with long minutes of gorgeous imagery. Shot by Christopher Doyle and Kathy Li in a fluid style that illustrates Alex’s infatuation, the skaters appear in grainy slow motion and blurry close-ups, their loose jeans and casual athleticism framed by shafts of sunlight, under Nino Rota’s enchanting score for Giulietta degli spiriti. Approximating Alex’s perspective even as it follows him in shimmery, fluorescent-lit school hallways and dusky sidewalks, the handheld camera never presses for revelation, even in close-ups. His face pale and pained, Alex struggles to say what he means even in his notebook, his pencil scratching the page repeatedly, marking down the title “Paranoid Park.”

The Park is significant not only for the sense of belonging it promises, but also for the respite it offers from his diurnal life. When he speaks with his father, en route to a divorce with his mother and moving his things out, the camera keeps so tight on Alex’s face that dad remains nearly unrecognizable in the background, hugging his tattooed arms as he complains about Alex’s mother. “I never in a million years wanted anything like this to happen,” he says, dutifully.

At the same time, Jared is less and less visible, distracted by his efforts to “get laid.” (“What I really wanted,” Alex says in voiceover, “was to skate with the hardcore freaks at Paranoid Park.”) Even less compelling is Jennifer (Taylor Momsen), Alex’s cheerleader girlfriend. “Jennifer was nice and everything,” he sighs, “but she was a virgin, which meant that she’d want to do it at some point, and then I knew things would get all serious.” Though she wonders that their first time is so unclimactic (“Do you think we should do it again?”), she’s also pragmatic. Slipping on her bra and jeans as the camera shoots from behind Alex’s head, still lying on the bed, Jennifer walks off the shadowy screen as she calls a friend to report: “We totally did it. It was fantastic.”

Alex is less enthusiastic, in large part because he’s haunted by a night at Paranoid. Though he tells no one about it, he broods on it, the story emerging slowly, in seemingly scattered flashbacks. Based on Blake Nelson’s young adult novel, the movie realizes Alex’s desperate, poetic subjectivity in layers. His halting voiceover is perfectly unmatched with the uneven editing and skips back and forth in time. “I’m writing this a little out of order,” he says, “Sorry. I didn’t do so well in creative writing, but I’ll get it all on paper eventually.”

It’s not until late in the film that you realize he’s reading a confession. It begins at Paranoid, where he meets Scratch (Scott Patrick Green), older and scruffy-bearded. He invites Alex to the railroad yard for a beer, and the boy goes along, mostly, he says, to ride a freight train. This one night out changes everything for Alex, when he’s accidentally responsible for the death of a night guard at the tracks. Left alone and unnoticed when the older skater runs off, Alex soon faces questions from Detective Lu (Daniel Liu), who comes to see him and his fellow skaters at school.

Assembled in an empty classroom, the kids shift in their seats (like Nevin, these mostly nonprofessional actors auditioned for Van Sant via MySpace). Lu explains they’re not suspects, but rather, “I’m trying to get to know about the skateboard community.” A kid in the back calls out, “It’s not like a community. It’s not like we know each other.” Corrected and plainly unable to get through, the cop tries again, laying out photos of the body (which was cut in half by a train), in full grisly color. The boys smirk and snort, like they’ve seen too many TV shows with more affecting imagery. Alex looks at Lu, their gazes locked. “I had tried to put this part out of my mind,” he says in voiceover, “but Lu’s picture brought it all back.”

Alex struggles with what seems an inevitable sense of guilt and remorse, but he’s also hopeful that he can elude actual consequences. Not because he doesn’t feel bad, but because he didn’t mean to do it. Remembering the night, he distinguishes between knowing he should “tell the truth” and wondering what that truth might be. “My body didn’t care,” he recalls, “My body only wanted one thing to get the hell out of there.” He’s not looking for redemption or even to do the right thing. He only wants the night to go away, so he can go back to Paranoid without being reminded of what happened.

Only his friend Macy (Lauren McKinney) notices that “something’s happened.” Alex nods but can’t say, only offers an approximation of what he’s feeling. “I just feel like there’s something outside of normal life,” he says, almost urgently. “Outside of teachers, breakups, girlfriends, like right out there, like there’s like different levels of stuff and there’s something that happened to me.” She suggests that apologizing will ease the burden. He should write it in a letter to someone he trusts, she says helpfully, even if that person doesn’t read it. Macy’s making her own shy bid for his attention, but Alex can’t see that. His view remains limited and warped, teenaged and confused. And so the film closes with still more images of skaters, these reflected in wide-angly convex mirrors, beautiful and frightening and seductive.