A rat sitting on the author’s shoulder calls Passing for Human a “neurological-coming-of-age story“. The rat, an embodiment of Liana Finck‘s debilitating doubts and self-criticisms, is of course wrong. Though her life is inevitably experienced through what she only indirectly identifies as Aspergers, Finck’s tale is a multi-generational creation myth, biblical in scope and tone. Her focus is often much more on her parents and how their struggles eventually formed the foundations of her own. While events seem real, their telling is also magically real, combining matter-of-fact facts with literalized metaphors that assume the role of ongoing characters in a personal fairy tale.

The two rats nibbling at her shoulders appear multiple times, even compelling Finck to ball up and throw away her first two attempts at “Chapter 1”, resulting in a new title page, epigraph, and first chapter start appearing anew on page 63, and then again on page 107. Though the rats eventually vanish (a sign of hope for Finch’s mental state), the do-over book structure continues for a grand total of five distinct chapter ones but no chapter twos or threes or fours. Since each new chapter one is presented as a necessary corrective for the failures of the previous attempt, it seems Finck finally gets it right—or at least her silenced rats finally think so.

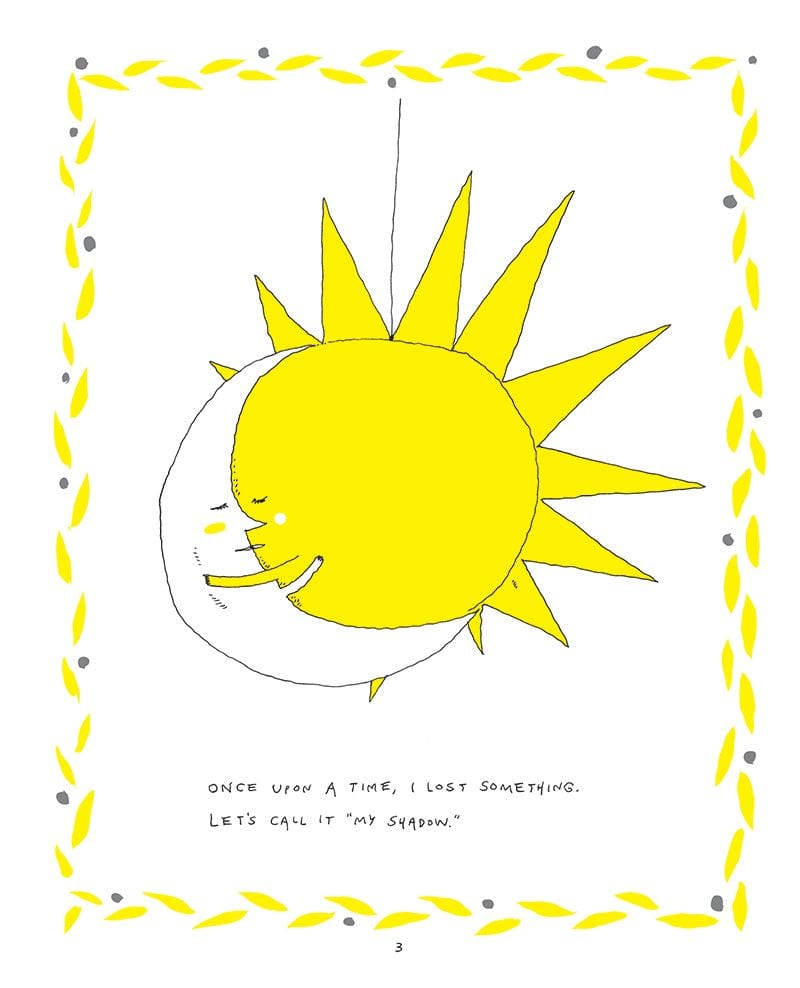

While the rat conversations are easily understood at Finck wrestling with her insecurities, particularly her internal editor, other unreal characters are more ambiguous. She introduces her mother’s “living shadow”, one that “can move, and talk, and think on its own”, early in the first first chapter. Rather than providing rat-like commentary, the shadow takes a central plot role, supporting or departing or returning at key points in her mother’s life. At various times the shadow seems to represent her creativity or her soul or her confidence or her ambition or her guardian-angel-like instincts or even an emotional crutch holding her back. Other times it’s a full-fledged character who can let her down or whom she can reject or pine for.

We meet Finck’s shadow too, another unreally real character with the same ambiguous qualities as the mother’s. It even narrates the final chapter one, in a reversed world of white lines and letters on black pages. No surprise, the two shadows know each other and together fill-in missing details from the previous chapters, explaining where they went and why during periods when Finck and her mother lived shadow-less.

If this doesn’t sound like your standard memoir, it’s not. Finck infuses her storytelling with so much genre-bending invention, it’s not clear whether Passing as Human is a graphic memoir at all. It begins with a prominent, hand-written disclaimer: “some names (including mine) have been changed. Some facts have been tampered with. All characters, especially my parents, are seen through my eyes, when I was younger.” Sure enough, Liana is called “Leola” in the text, an easy enough substitution—but to what end? The switch disguises no one, not even in the rudimentary Roman à clef sense where a reader need only decode a set of names to unlock the references.

Finck also labels a central boyfriend “Mr. Neutral”—unless we’re to understand that those letters are literally printed on his t-shirt as they appear to be? Either way, it’s not a name, it’s commentary, and no cause for a disclaimer. But I wonder whether Finck’s concern is in the “graphic” rather than “memoir” half of her genre label. Is a misleadingly inaccurate drawing of a someone still a factual depiction? Is getting something wrong the same as fictionalizing it? Finck’s character (it’s unclear whether this is Liana or Leola or what the difference might be) admits as she draws Mr. Neutral: “I didn’t get the nose right, or the hair—and then I thought maybe I can pretend I was just trying to draw an abstract shape … I can’t decide when lines are the right lines—and whatever I was drawing becomes a scribble.”

Lynda Barry paved this path almost two decades ago when she playfully coined the term “autobiofictionalography” to describe her own almost-memoirs. Also, like Barry, Finck longs to “draw the way I did as a kid”, which is perhaps why her style is so aggressively rough, with figures defined by only the barest, black lines, faces and anatomy evoked more than fully sketched. Even when she draws shadows, either as characters or as actual darkness, she highlights the haphazard patterns of her penwork. Even in her black and white world, nothing is simply and solidly black.

The artwork is a comic in the cartoonish sense of simplified and exaggerated illustrations warping and arranging autobiographical material freely. But where Barry’s equally dominant words seem factual, Finck’s divisions are less clear. Yes, the visual content is inevitably warping, is inevitably from a point of view in both a literal and psychological sense. But the fantastical elements aren’t limited to the visuals. And what exactly does it mean to “tamper” with a fact?

James Frey was labeled a fake when details in his 2006 memoir were revealed to have been untrue. It turns out he wrote A Million Little Pieces as autobiographical fiction, but when he couldn’t get it published, he presented it as memoir instead. Finck is doing nothing of the sort. Or so I overwhelmingly assume—though there’s no key here for decoding which facts are facts and which are tampered facts. Did her mother impulsively quit her job at an architectural firm to marry Finck’s father and move to the country to design and build that surreal, half-circle of Finck’s childhood home? What if anything in there has been tampered with? But happily in this case, Oprah Winfrey’s initial defense of Frey (she later withdrew it) still stands: “The emotional truth is there.”

I also suspect that the decision to label Passing as Human as a “graphic memoir” rather than a “graphic novel” (an already ambiguous term, since it sometimes is understood to include nonfiction) was a marketing one. If Finck were working with a prestigious but smaller, comics-focused press such as Drawn & Quarterly, Fantagraphics, or Pantheon, I wonder if the words “graphic memoir” would be on the cover. Since comics are still suspect in some literary circles, Random House may be playing it safe by evoking the comics subgenre with the highest literary credibility.

But whether “memoir” or “novel”, Passing for Human is foremost “graphic” in its artful use of the comics form. “The most important part of a story,” writes Finck, “is the blank space. You look at it and see what you want to see. Most storytellers don’t know this. They are dazzled by words.” Finck dazzles with her minimalist lines, which include the simple grids of her panels and gutters. And her plot is an artist’s plot, a kind of mystery or vision quest: “A drawer doesn’t draw because she loves to draw. She doesn’t draw because she draws well. She draws because once she lost something. And by drawing—she will find it again.”

I can’t say whether Liana or Leola Finck finds that ever-lost something-or-other through the fictional sketches of their mostly-true memoir. But I can say it’s a pleasure to be invited on the journey.