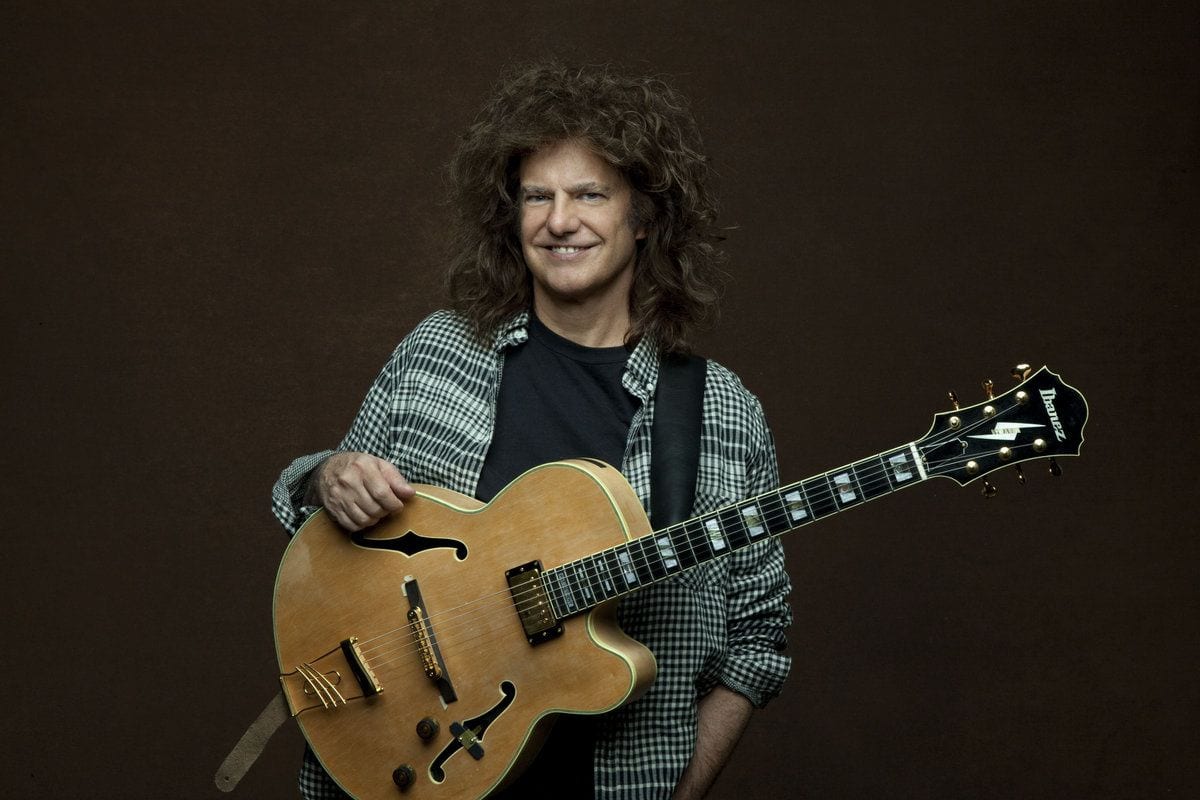

Guitarist Pat Metheny is the jazz world’s most multi-faceted star. He straddles accessible sounds for non-aficionados while still maintaining credibility as a creative and original voice. With his Pat Metheny Group, Metheny created music throughout the “smooth jazz” era that was melodic and easy on the ears, using pop hooks and Brazilian sway. At the same time, he kept busy with more daring projects allying him with the iconoclast Ornette Coleman, the composer Steve Reich, and an array of jazz-world peers. Metheny has been keeping his artistry nutritious as well as tasty—never a simple balancing act.

In recent years, the guitarist has demonstrated particular eclecticism. He’s been composing and performing for his “orchestrion” (a set of mechanical instruments triggered by his guitar), appearing as a sideman with many other great musicians (such as trumpeter Cuong Vu, a former member of the Pat Metheny Group), fronting the Unity Group with saxophonist Chris Potter, young bassist Ben Williams, and astonishing drummer Antonio Sanchez, and playing compositions by John Zorn. At the same time, he was playing and touring regularly with a new quartet that is arguably the most versatile regular group in his career: Sanchez, wunderkind bassist Linda May Han Oh, and pianist Gwilym Simcock. In concert, this band played tunes from across Metheny’s catalog with an openness and sense of exploration that the old Pat Metheny Group never tried to match.

From This Place is Metheny’s first studio recording of new tunes in six years and the first outing fo the touring quartet. Coming off touring, he presented the musicians with new compositions, seeking to capture the adventure of tackling them fresh in the studio. That approach, alone, would have been fairly conventional. Metheny decided to add another element. With these recordings in hand, he brought in arrangers Gil Goldstein and Alan Broadbent to create an orchestral accompaniment to be layered atop the quartet’s existing work. The leader explains that he was thinking of the classic recordings made in the 1970s on CTI Records, where great players like Freddie Hubbard and Milt Jackson were given studio sweetening of this sort.

Those CTI records, of course, could also be schmaltzy, going a little too far—precursors to the candy-coated jazz that Metheny has been so adept at sidestepping.

The better comparison than those CTI records might be the second half of drummer Terri Lyne Carrington’s superb 2019 release, Waiting Game, on which subtle orchestration was added after the fact to a similarly-instrumented quartet’s exploratory improvisations. Although the tracks on From This Place are composed—and, indeed, they are generally tuneful in the vintage Metheny mold—Goldstein and Broadbent have composed gentle cushions that shade, highlight, and emphasize all the elements of these performances, including the solo sections in which the members of the quartet are in conversation with each other. The Hollywood Studio Symphony effectively becomes a fifth player in that conversation. Most of the time.

It has always been a challenge for musicians to fuse the rhythmic surprise and spontaneity of jazz with the textures and orchestral possibilities of classical music. Here, the orchestra rarely surges into the foreground with its own agenda. To an even greater extent than with those CTI dates, the production keeps the strings subtle and gauzy. The quartet and the strings are not equal partners as they are on the recent recording Sun on Sand from saxophonist Joshua Redman and Brooklyn Rider. Rather, the quartet is the star, playing the themes and shooting the musical fireworks into the sky.

The surest Metheny-style pleasures are here in spades: catchy melodies and a thrumming rhythmic excitement that nods toward pop music even as it grows complex. “Pathmaker” has a fleet theme that lets the guitar and piano lace together ingeniously, but it lets the orchestration kick in under a swaying secondary section that gives Metheny and Simcock a platform from which to launch lyrical improvisations. The quartet will nudge away the strings in moments of urgency and then open up room for them again, organically. In its last minute, the performance gives the orchestra its own coda too. “Wide and Far” is another patented Metheny romp, with Sanchez playing a quiet double-time groove that urgently pushes a gorgeous set of chord changes. The orchestra can be a bit more active here without getting in the way, particularly as its low brass brings out the bottom of the tune. Both guitar and piano are given generous space to stretch out in improvisations.

An even more compelling collaboration happens on the Latin-groove-driven “Everything Explained”, an uptempo number where the quartet is in such command that the orchestra’s involvement feels integral and sewn into the fabric of the arrangement. After Metheny’s solo, Simcock duets with Sanchez for a glorious few minutes, where the arrangers understood not to get in the way, bringing the larger group back later when the leader is flying and the strings and woodwinds make more sense.

There are special guests on two tracks. A standout moment features Meshell Ndegeocello singing gently on a Metheny ballad. It is as quiet and pretty as either artist has ever sounded, with Ndegeocello’s tone and Metheny’s acoustic guitar acting as natural partners and the strings present without treacle or sentiment. The singer is deployed gorgeously, her voice layered in gracious call-and-response, bouncing from one channel to the other, sometimes doubled. It is a piece of music that sounds very little like either artist’s previous work while, somehow, being distinctively theirs. It’s the shortest thing on From This Place, and its one miracle.

“The Past in Us” is a feature for harmonica player Gregoire Maret, and it certainly begins differently from most of Metheny’s music—with a short “concerto” section for Simcock and the orchestra playing a lyrical but slightly sanitized opening. May Han Oh’s entrance injects deep feeling, and Maret’s melody is sad and lovely, with Metheny weaving around it—again on his acoustic guitar. The combination of strings and band here sounds a bit more from another era, maybe like a nice soundtrack from the 1960s. But it still works.

There are other tracks where the combination of orchestra and band is less optimal. “Same River” is built on an utterly grooving bass line from May Han Oh, and the orchestra enters quietly on top of it before Metheny’s slightly synthesized melody line begins. Here more than on most cuts, the extra strings seem to be gooping up the works, yes, sounding like some of the those CTI sessions from the 1970s, but not in a good way. The tune doesn’t need the extra drama, particularly when the best part of it is rhythmic energy between bass and drums. Metheny’s guitar synth loves to soar over the extra sound, but this performance begs to be decluttered.

“America Undefined”, the opening and longest track, is a tricky composition that works like a charm when the quartet is on its own, with Sanchez at his best and the sense of band interaction clear, but it feels bogged down when the strings interfere. The last five minutes, which are a fantasm of sound effects and gradual orchestral swell (presumably relating to the composition’s title), are the weakest stretch of the recording.

A couple of other tracks demonstrate how the orchestra’s strings can cause the classic problem: too much sweetness. The closing tune, “Love May Take Awhile”, sounds like an old-fashioned jazz-plus-strings session. It is a pretty ballad, but it is also the track that most downplays the band—it is really Pat With Strings. The orchestra plays a saccharine introduction, and it is largely given the reins in the last two minutes. The moms and dads of the 1960s would have been perfectly comfortable with this track being played on their “easy listening” radio station alongside the 101 Strings or Montovani. “Sixty-Six” begins in that territory, but the bass solo is expressive, and then Metheny’s solo gets a lift from a more active string chart, boosted by Sanchez’s help.

But this is the tricky territory that jazz musicians traverse when they put their bands together with big string sections. The history of using an orchestra to spruce up, legitimize, or sweeten the band catches up with them. That’s why perhaps the best track on From This Place is “You Are”, a chiming texture piece that sounds like it was conceived from the start with the orchestra in mind. Simcock’s piano plays a hypnotic four-note doorbell-like figure, joined over time by bass and guitar. Harmonies thicken the sound, then a guitar counter-melody, with the orchestra joining in a creeping, ominous way. On this track, the musicians are creating a piece that wouldn’t sound as good any other way. And, while the orchestra works on many of the tracks here (and doesn’t on others), this is the only piece that seems born to this approach.

It makes sense that “You Are” is also the only piece here that doesn’t feature sections where one musician takes off in improvisation, supported by the spontaneous accompaniment of bandmates that have toured with the musician for years. In those situations, the orchestra is almost always a bad partner, not having the nimble aural ability to respond in real-time to the subtleties of spontaneity. And while Goldstein’s and Broadbent’s orchestrations here are subtle and were written in response to the recordings by the quartet, they still aren’t as hip and interesting as a great musician inventing something in the moment. There remains magic of sorts to jazz, to the wonders of improvisation.

If Pat Metheny’s groups have been among the most accessible in jazz for the last five decades, it was not because they lacked any of that sparkling magic, that surprise. It’s here on From This Place as well. And the gauze of the orchestra mostly does not mute it. But, equally true: the spark is almost entirely coming from Metheny, May Han Oh, Sanchez, and Simcock. The orchestrations are mostly neutral, sometimes problematic, occasionally great. But: the quartet deserves an album of its own.