Paul Auster, the man who wrote a novel based on a wrong number, does not own a cellphone. He writes, rewrites, drafts, and revises – but does not own a computer. Yet there is one electronic format that Auster has decided to embrace: “I stopped smoking, and I switched to electronic cigarettes. I vape now.”

The man who wrote the films Smoke (Wayne Wang, 1995) and Blue in the Face (Auster, Wayne and Harvey Wang, 1995) vapes.

“My friend Art Speigleman was the most dedicated smoker I’d ever known. He smoked in Olympian quantities, and he was the one who switched to e-cigarettes first. I tried it, and I realized it was a good substitute.”

Blazing new trails, Auster has now released the manuscripts of his New York Trilogy, featuring handwritten and typewritten drafts of the three novels—City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room—previously available only by visiting the archives of the New York Public Library. But unlike e-cigarettes, they are not meant as a substitute, but rather a way for readers, like Auster’s characters, to investigate the mysteries of writing.

First published in 1985 and 1986, the New York Trilogy is, like Auster himself, simultaneously old-fashioned and hip and not what readers may have been expecting. He included a fictionalized version of himself in the story, something Brett Easton Ellis and Stephen King have done since. He made detective stories surprising and weird before The Usual Suspects (Bryan Singer, 1995) or Twin Peaks (Mark Frost, David Lynch, 1990-91). He blurred the boundaries between fiction and reality in ways that Charlie Kaufman has since made mainstream.

As Auster puts it, “A friend of mine, when he read Ghosts, said, ‘Do you know what this is? It’s a book about reading a book.’ And I thought, yes. I hadn’t consciously thought of that as I was writing it. But when my friend said this, it’s been hard for me to think of it in any other way.” Yet, despite that seemingly dry description, Ghosts is still a heart-pounding page-turner.

With the release of the New York Trilogy manuscript, the three novels bring newer and even deeper levels to understanding Auster, yet they are still only pieces. “There were many stages of each book,” says Auster, “But these are snapshots, I suppose, of each book at one moment or another.” The manuscript is large and lavish—as Auster puts it, “Vivid. You can see, for example, the difference between pen marks and pencil marks.”

Sure, New York Trilogy is a collector’s item, but it is also a potential resource for fans and scholars. “We went into the archive where all my papers are stored,” Auster says, “Because I kept changing the titles of the books as I was writing them, I think different versions were stored in different places. We took what seemed to be the most interesting example of each book.”

As we speak, Auster’s contradictions continue to unfold. Despite the title New York Trilogy, the novels were not originally conceived as a trilogy, and they were not composed as linearly as their neat binding suggests. Auster explains, “I wrote City of Glass straight, as a novel in itself, without any other connecting novels in a series. It derives a lot of its materials from work I did in my early twenties. I was trying to write a big novel then, and I couldn’t figure out how to do it. It was a mixture of what is today City of Glass and Moon Palace,” released later, in 1989.

[Courtesy SP Books]

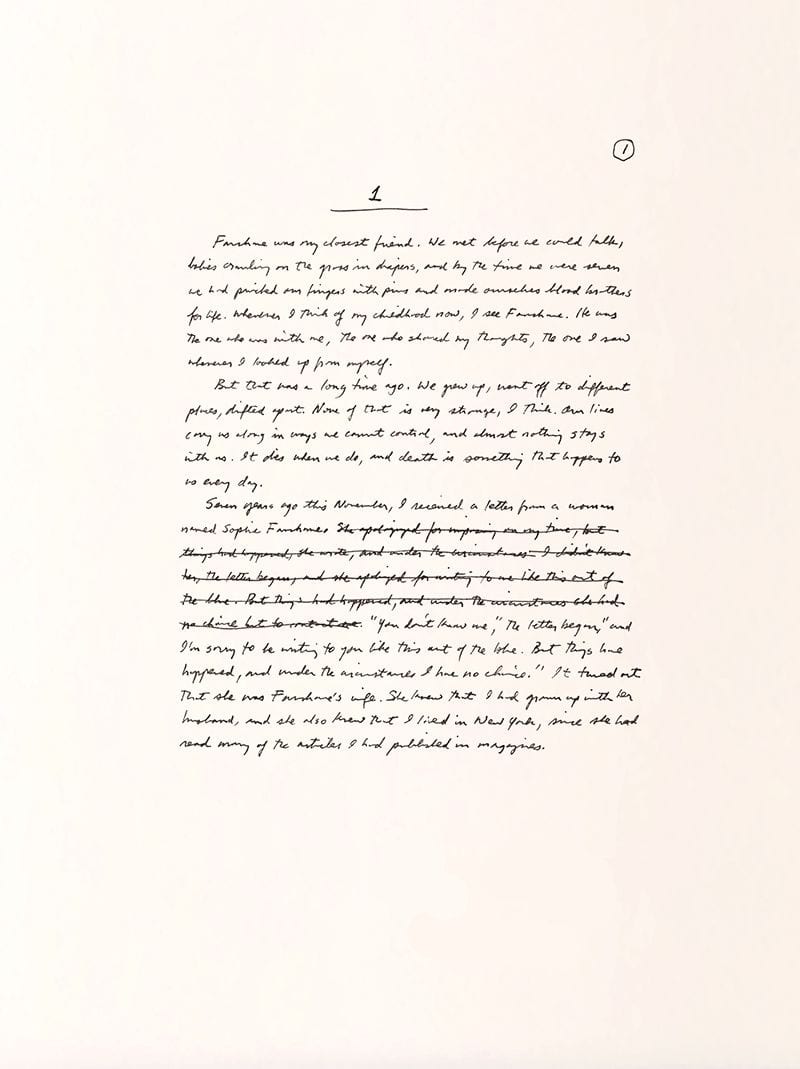

“I went back to these manuscripts from my early days in college and pulled out a number of passages that I wound up using in City of Glass. The footsteps in the street, the conversation of ‘Don Quixote’, and other elements as well had been simmering inside me all those years, and I managed to find a place for them in the novel.”

The manuscript, then, provides yet another layer of meta-commentary—the stories within the story, now a manuscript about the manuscript, packaged as a red notebook, an image that occurs separately in each of the three novels. If he had not already released a collection titled The Red Notebook (Faber and Faber, 1995) it would be a fitting title now. Yet Auster doesn’t see the manuscript in the spirit of James Joyce’s famous quip, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.” Auster insists that he never thinks about “these things”: “I don’t worry about what people think or how they’re going to interpret it. Life is too short to worry about other people’s thoughts. I don’t concern myself with that. It’s a blunt but true answer.” Literary analysis, Auster says, “serves a great purpose, but it’s for other people. It’s not for us.” Writers, he says, “need to keep our heads in our work.”

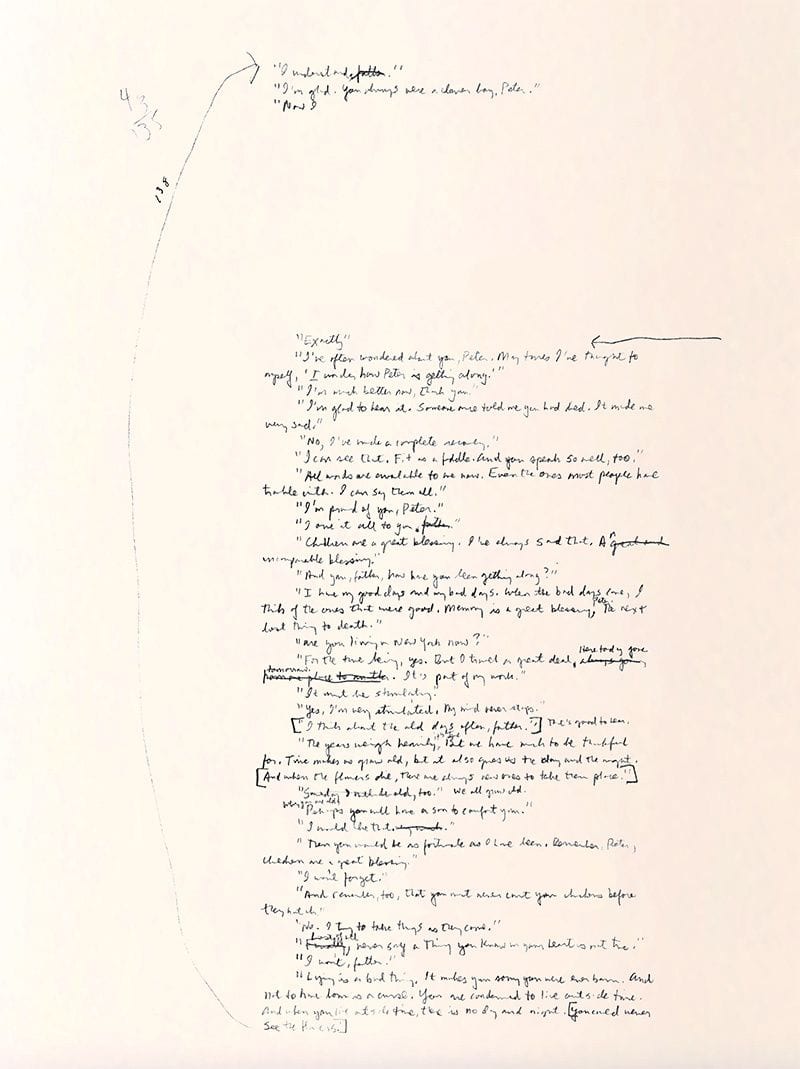

Still, the early drafts create additional layers of meaning, especially hearing Auster explain the changing titles that complicate the collection. The titles, like the characters in the stories, share overlapping names and mistaken identities. City of Glass was initially titled New York Confidential, The Locked Room was called Ghosts, and Ghosts was Black outs [sic]. “The second book was based on a play that I wrote in the seventies called Blackout and it was three characters in a room, a story of a man coming to listen to the report compiled about him.”

So far, so Auster-esque—except Auster didn’t like the play, and it was never performed.

[Courtesy SP Books]

“But after I finished City of Glass, I thought, ‘Hmm, that old play somehow resonates with the book I just finished.’ I revisited the play and understood that I could tear it apart and build it back up as a fulcrum between the two larger books, not that any of them is very large. That’s how the title ‘Blackouts’ got used—during the play, the lights go out, Boom!, and then the action continues.” Once Auster realized he had two interrelated books, he “knew there had to be three, and then The Locked Room grew out of writing the other two books. I was following my nose and blundering blindly in the corridors of my imagination.” In that sense, Auster sounds like his own protagonists, and the manuscripts themselves, despite the notes and details, demonstrate some of the progressions and histories behind each work.

Is it possible, though, that “Black outs” might still be the better title, with its overlapping meanings of power, alcohol, and stage and film transition, consistent with the color motif in a story featuring characters named Blue and Black? Auster seems game: “There were also black outs during bombing raids in cities. I think that’s the principle meaning of black outs. And black out shades, so that light doesn’t come seeping through windows when bombs are falling.” So maybe it is a better title.” And isn’t the title Ghosts better suited to The Locked Room, about a writer named Fanshawe who disappears, leaving his manuscripts and life behind to haunt the unnamed narrator? Auster remains playful but noncommittal: “I love making up titles. I just make them up for the fun of it. I have lists of titles of things I’m never going to write. Sometimes I give them to friends. I say, ‘Do you like this one? Here, take it.'”

Close readers will notice other differences in the drafts. The opening line of what’s called Ghosts here, but that readers know as The Locked Room, appears in the manuscript as “Fanshawe was my closest friend“; in the published version, it reads, “It seems to me now that Fanshawe was always there.”

“Well,” Auster says, “it’s a better sentence. You get an idea, but you haven’t formulated it clearly yet. And then, when you have lassoed that idea, you can mull it over more quietly and really think through the ramifications. That blunt statement evolves into something a lot more subtle.” In other words, does the revision sound more like a Paul Auster sentence than the original? “Yes, exactly. And those, of course, were my first novels. I had written fiction, hundreds and hundreds of pages, but I had never really found my way of doing things.” His style, he said, has “evolved over the years, and I think it keeps evolving.”

Other elements in the manuscript are less straightforward, including what looks like math problems, sometimes scratched out, on the backs of pages and in the margins. Auster doesn’t quite remember what he was calculating, but “it could be the number of chapters. I was always keen for those books to have an odd number of chapters. I know this sounds strange. Thirteen chapters in City of Glass, nine in The Locked Room; Ghosts has no chapters at all, no breaks even. Because if you have an odd number of chapters then there is a chapter that is dead center, and that appeals to me. I’ve since abandoned this obsession, but for a while I was fixated on having a book with an odd number of chapters.”

But despite the affinities for odd numbers, doubles, and what seem like novelistic games, Auster doesn’t see himself as many readers and critics do. “Poor Quinn”, the main character in City of Glass, is a “man without friends, without any life at all. And he’s in mourning. There was a theater adaptation done in England. I read an interview with the playwright who did the adaptation, and he said, ‘When I read City of Glass when I was very young, I thought it was very clever, a clever book. But now that I’m older and a father, I understand the pain and suffering and grief behind it,’ and I thought that was a remarkable thing for him to say. That for me is what’s behind the story, this absolute melancholy after [Quinn’s] wife and son died. We never know how. He’s been cut off from the things he cared about, and he’s surviving in this posthumous life.”

But aren’t the novels filled with astute observations, narrative curves, and breaks with convention? “Everyone thinks I’m this clever fellow, but I’m not!” Auster insists, laughing. “I’m very down-to-earth and full of feeling and I tear up frequently. I’m not a cold calculating machine that puts out clever books. It’s all very deeply felt.”

With all the possibilities the manuscript provides, it also suggests that the next generation of writers may not have such archives, since many default to word-processing without hand- or type-written drafts, or any discrete drafts at all. “But I, being an old dinosaur that I am, still don’t have a computer. I still write all my books by hand, and I still type them up on my old manual typewriter, probably manufactured in 1960, in what was then West Germany.”

So do writers lose something by forsaking longhand and typing? Despite his own inclinations, Auster doesn’t think so. “I wouldn’t say anything. What works for one person doesn’t work for another. The only thing that matters is what it looks like in the end.” Auster isn’t prescriptive. “Everyone is different, and everyone needs a different way of doing it. When I’m writing with a pen, I feel like I’m scratching words into the page, and that the words are flowing out of my hand, which is connected to my heart and my mind. It’s a very physical process for me.”

Like the era of the typewriter the days of wrong numbers – especially Auster-esque portentous wrong numbers – seems over. But Auster disagrees: “I still get wrong numbers all the time.” Because, of course, it turns out that he uses only a landline. I had desperately wanted to quote from the beginning of City Of Glass to kick off our interview:

“Is this Paul Auster?” asked the voice. “I would like to speak to Mr. Paul Auster.”

I assumed he’d heard it a million times, and that when he wrote those lines he must have imagined that they’d come back, another ghost, to haunt him. He hadn’t. “When I dreamed of becoming a writer when I was very young, it never occurred to me that you’d do anything but write the books, send them to the publisher, if you were lucky enough to have one, they would print the books, and that would be that. This idea of doing readings and interviews, it never occurred to me. But it is funny.”

If celebrated author Paul Auster never envisioned his future as a famous writer; if celebrated smoker Paul Auster never imagined himself vaping, what else lurks in his locked room? “Well,” Auster concludes, “I’ll tell you a secret: I’ve never really thought of myself as a novelist. I think of myself as a storyteller. And I think I’m much less influenced by novels than by more primitive forms of storytelling, like fairy tales.

“4321, the latest novel I published, that immense book that nearly killed me, that came out early last year? It’s 900 pages, tight print, and it’s all telling. All telling. Everything the teachers tell you, about ‘show, don’t tell’? You know, it’s such garbage. Anyone who would tell a writer that there’s one way to do things is a fool.”

Going by the multiple versions of the New York Trilogy manuscripts, Auster understands that there are many ways to do things, and it’s clear that he has found many different pathways to tell his stories. Even without a GPS device.

*

Limited quantities of New York Trilogy are available from SP Books.