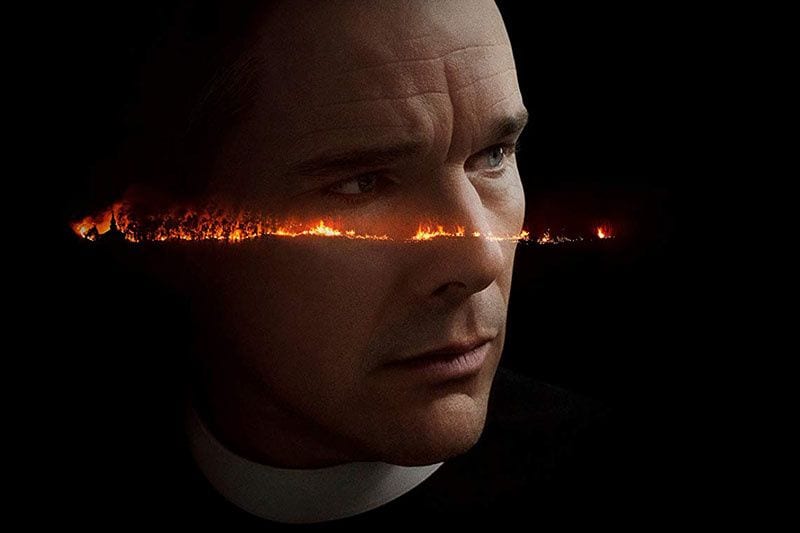

Paul Schrader‘s intellectually inclined First Reformed (2017) tells the story of Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke), a solitary parish priest at a small church in upstate New York. When approached by a pregnant parishioner played by Amanda Seyfried to counsel her radical environmentalist husband, Toller begins to re-experience his own tormented past. The encounter leads him to question the meaning of his own future and whether mankind will be granted God’s forgiveness, the interrogation only compounds his feelings of despair that forges an ambiguous future.

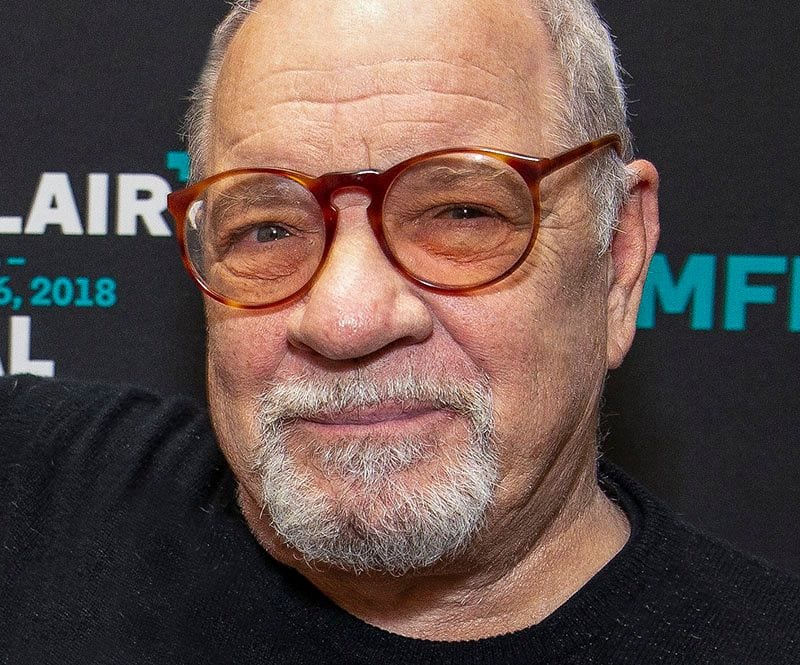

While Toller’s encounter dredges up his own past torment, First Reformed bridges Schrader’s intellectual past with his present. “I had written a book about spirituality in cinema when I was a graduate student,” [Transcendental Style in Film, University of California Press, 1972] he explains. “But I had never made a film in that way, and I always said that I never would.” Speaking with PopMatters, Schrader explains the reasons for going against his original decision, and reflects on the legitimacy of spirituality in the cinema, and how a state of permanent transition is impacting our knowledge of film and the practice of filmmaking.

Why film as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

Well, I think it was just a generational thing. Maybe it wouldn’t be film today; if I was younger it might have been novels or plays. I really came of age in the European cinema of the Sixties and that was the cinema that really defined me, and made me want to be closer to movies as a critic. And so, when it came to that moment to move from non-fiction to fiction, it was just logical that I would move onto a script.

Over the course of your filmmaking career, how has your understanding of cinema changed?

Movies are in enormous flux and I used to think we were going through a period of transition. Now I think that we are in a period of permanent transition, and every year is going to be different, with different models of distribution, different ways to make films, and virtually everything we have learned in the last hundred years doesn’t apply. So every time you do a new film, if you really want to press yourself, you have to figure out, other than actually doing them right now, what is it like to make a crime film in the year 2016? What is it like to make a spiritual film in the year 2018? And then you address it in that way.

In regards to genre cinema, there’s the supposition that they chronicle social angsts and preoccupations across the decades. However, is this a characteristic of not just genre film, but more broadly of the cinematic art form to portray the period in which films are made?

It’s certainly true. I can flip on the TV and if there is an old movie on, I can usually guess within five years when it was made.

Interviewing Agnieszka Holland I asked her, “Across the decades, the feel of film has changed. For example, the American gangster film of the ’40s has a different feel to the gangster film of the ’70s onwards. Do you believe this shift is caused by more than technological developments, and may reflect a changing aesthetic?” She offered: “I think it is something that is more mystical — a mystery that is included in the particular film, and which doesn’t age.” Would you agree that there is a spiritual element to cinema?

I think cinema is inherently anti-spiritual. Its two great engines are action and empathy. You see an image of a person or a place and you empathise, and then that image starts to move. Action and empathy are not really in the transcendental tool kit, and so when you decide to work on the contemplative side, you are working against the two most powerful creative, commercial engines of the medium.

Movies were not made to be static, and so you have to be very careful because you can do some magical things when you work on the slow side, but it is a very tricky dance. I don’t think that cinema is inherently spiritual, I think it is inherently visceral.

What was the genesis of First Reformed? And to speak about themes, are you attentive to specific ones from the outset or is it a journey of discovery?

I would say I know it from the beginning and this film in particular had an intellectual birth. I had written a book about spirituality in cinema when I was a graduate student, but I had never made a film in that way, and I always said that I never would. Then about three years ago after a conversation with Paweł Pawlikowski, who did Ida (2013) (2013), I said: “Okay, it’s time now; it’s time to do that script you always said you wouldn’t write.” And so I made an illogical decision to go there. Then it was just a matter of thinking about it and re-watching the two dozen or so films of that nature that had meant something to me, and saying what is the best structure and format?

What was the reason that made you feel this was the time to go against your original decision?

It was two things. One was my age; I was going to be seventy next year, but also it was the dramatic drop in the cost of making a film. I always felt it would be financially irresponsible to make one of these films in America. The European counterparts all had subsidies of some sort, but we do not, and if I were to ever have tried to make a film like this, it would have been financially irresponsible. It would have failed and I wouldn’t work again, so I just didn’t want to go there.

The cost of making these films now has dropped so rapidly, and I made this film in twenty days. When I began my career it would have taken forty-five, so half as much, and so films that were much too financially irresponsible, are now going to appear more responsible. So I began to think: Yes, it is possible. It is now the right time in my life to make this movie. But it was also the right time with film technology for me to make this movie.

Cinema is a communal language and in spite of the film process being unoriginal, it is the capacity of the individual filmmaker to bring something unique to a film. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on this in relation to those films that influenced First Reformed.

All any artist is ever doing is collecting influences, sources and experiences, and putting them together. That’s what we do and any artist that says that’s not true is lying. So you start thinking about your influences and I picked up the character from Diary of a Country Priest [Robert Bresson, 1951], and I picked up the journal from Country Priest and Pickpocket [ibid]. I picked up the premise and opening shot from Winter Light [Ingmar Bergman,1963), the ending from Ordet [Carl Theodor Dreyer,1955], the barbed wire from Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood (1979) [directed by John Huston], and on and on. I picked up stuff from Taxi Driver [Martin Scorsese,1976] and as you mix up all these influences they start to create a new object. One of the amazing things about First Reformed is it’s made with so many old film techniques, yet at the same time feels of this moment.

What is the place of storytelling within the contemporary world, and the value of cinema as not only a medium that offers an escapist pleasure, but something that can resonate more deeply? And do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect for both the filmmaker and the audience?

Well, there are a lot of different reasons to go to the cinema and I’m just happy as the next person to be diverted and entertained. But there’s nothing wrong with being an elitist, and nothing wrong with wanting to appreciate the best and to strive for it. It can happen that way, but life changes us all the time… and so you could have a film that changes you, or you could have a film that changes you very little.

First Reformed is released in UK and Irish cinemas on Friday 13 July 2018 by Picturehouse Entertainment.