The Pyramid Texts is a bold feature debut from directors Paul and Ludwig Shammasian. The monochrome tones meet with the poetic rhythm of an aged fighter’s philosophical monologue that transforms the squared ring into a thoughtful and spiritual space. It offers a different vision to the more common association of blood, sweat and violence as Ray (James Cosmo) records a video for his estranged son. Here is a masterful example of how the intimacy of a characters life can simultaneously have a universal thematic resonance, namely of fear that connects and binds us.

In conversation with PopMatters, Paul and Ludwig Shammasian reflect on The Pyramid Texts as a celebration of words and the dismissive point of view encountered towards dialogue from scriptwriters. They also discuss the challenges of turning writer Geoff Thompson’s monologue into a film, the personal and diverse response to the film from audiences, as well as encountering the ambiguity of who is the author of a film.

Why filmmaking as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

Ludwig Shammasian (LS): Well I started off mainly in photography, so I was in the visual arts already. I still enjoy and continue to do photography now, and obviously while doing photography I started experimenting in videos. It’s just the fact that it’s quite a three-dimensional medium. You get to use photography, but you get to use sound as well, and you get to use story, and for me it was always about telling stories. That’s what I enjoy about photography and it’s what I enjoy about film. I always loved film and when I started experimenting in that medium, it just felt really powerful and a good place to be, and it went on from there.

Paul Shammasian (PS): I was lucky enough to know when I was young that I liked film. I enjoyed the art of film and the art of storytelling through that medium. Some people when they are born like music or playing the guitar, or the piano, and my first love of film came at a young age, and it just developed from there. I was making short films and as I was getting older my friends were filmmakers and actors, so we used to get together on the weekends and do little shorts. I don’t think there was a defining moment, I just think it was something I had always been involved in from a very young age.

Have your experiences as filmmakers influenced the way you watch films as spectators?

LS: I thought that it would really change the way I watch and experience films, but strangely I don’t think it has. I watch films and I genuinely just switch off from being a filmmaker and try to appreciate the film. I tend not to think: Oh, I would have done it like that. If I enjoy the film what I normally think is: Wow, how did they do that? Or: That was fantastic! I’m glad that is the case because film can be so immersive, and what I look for in a great movie is to get lost in the story, to be lost in this moment. I still have that and so I just try to switch off and enjoy it if I can.

PS: I tend to look at films and appreciate them more because I look at the craft that’s gone into making them. Sometimes I’ll watch a film and I can take things away from it. I can sometimes learn and appreciate how simple something is, or the techniques they’ve employed in making a scene more emotional to forward the story in interesting and intriguing ways. So I think it influences me and I do get lost in it. But I am also looking at how they’ve achieved a certain state of emotion through their craft, and I actually enjoy looking at it from a professional perspective.

The way in which the character in The Pyramid Texts expresses his identity and emotions through speech crafts a film that is a celebration of words and language.

LS: The Pyramid Texts is obviously a monologue, and when it came to us it was a 30- or 40-page continuous stream of dialogue. Geoff [Thompson] didn’t write it as a stage play, a lot of people think that was the case, but he actually wrote it as a monologue and wanted us to turn it into a film. That was the initial intention and when I read it I knew the intention was for us to look at it as a movie.

But after the first page or two I literally forgot that I was reading something that could become a film. I think partly because it was so different, partly because it was a monologue, but also it wasn’t in a traditional script format. It was just dialogue and we were not looking at much direction on the page, and so I became lost in those words, lost in the character and lost in the story.

So that’s what did it for me emotionally. I couldn’t stop reading it and I finished it thinking that it was probably the most incredible thing I’ve read. We’ve read quite a few scripts over the years and of all the scripts we read that year, it was the most powerful.

So the next question was how do we make this into action because that’s what we do. We weren’t going to turn it into a stage play because we make films. Can it be made into a film and could we do it as a 90-minute piece able to sustain the audience? That’s when the questions started coming to us.

But in terms of answering your question, I think in this particular film the words and how they’re said are incredibly important. Interestingly, we hardly changed a word, which is very rare. I called Geoff and said: “This is literally word perfect. It’s just perfect.” Then I said to him: “We are going to find out one day that you didn’t write this.” It’s almost like a masterpiece written a hundred years ago that has been lost — it was a compliment and I was having a joke with him, but there was that thought in the back of my mind that this was some hidden masterpiece. That’s how compelled I was to want to make this into a movie.

PS: I’d like to add that it is poetry because when I re-watched it, I was always picking up on how something that he [James Cosmo] says at the end references something that he says at the beginning. People who have seen it a second or third time have said they didn’t realise there was a connection between certain metaphors he was using — talking about wrapping the hand to wrapping the child.

Having a film that’s so heavy with dialogue is one of the most difficult things to accomplish, and when you sit down with other scriptwriters they’ll say that you should be able to watch a film mute, and it should make sense. Dialogue is only to forward the narrative, but it should do no more. But the interesting thing is when you can achieve the opposite.

I remember when I heard that and then watched, for example,Pulp Fiction, where for ten minutes they are talking about their Big Macs and French Fries. They’re talking about what the metric system is, and I thought: This is so unique, it’s so different, it’s so engaging. So the actual dialogue is vital to the feel of The Pyramid Texts and what the purpose is.

LS: I would like to add that there was no reference of another film like this. There are many films that are one-handers: Buried [Rodrigo Cortés, 2010], Locke [Steven Knight, 2013] and I think there’s a new film called Nightingale, which is probably actually quite similar to this one. I haven’t seen it yet, but the ones we know of like Locke and Buried, they’re talking to other people. They are one man, but they are interacting, usually on the phone. In this film, he was literally talking to a camera or to himself, and so the words were very important.

As Ludwig has noted, cinema is an inclusive medium and so this restrictive approach to dialogue you’ve encountered could be seen to do film a disservice. The brilliance of film is the way in which it merges the art forms and allows for a nuanced approach to storytelling.

PS: Completely! I think there is a balance between having a lot of words and having an action film. If you go in one direction and you go all the way with it, say for example with The Pyramid Texts, then you have to have an actor that can actually deliver it. Already you are limited by how many actors can pull off a one-hander monologue for such a long time.

If we think about Shakespeare, he crafted whole stories with just words, but the stories were fantastic in themselves, yet few actors could do it well [except] Laurence Olivier or Richard Harries. You could comfortably watch them read a phone book and it would just be amazing. So I’m always careful because you can write something with a lot of words, but you have to find the right actor that can comfortably deliver it.

I’m the opinion that I love those moments when an actor can express themselves honestly with a piece of dialogue and there are no other cuts. It’s the chance to see them perform a scene which is very emotional, and there’s nothing else going on. I look for those moments in a film and I think those are the moments that hit me the hardest.

For example, Born on the Fourth of July [Oliver Stone, 1989] is one of my favourite films and there’s a scene in it where Tom Cruise goes to the family of the soldier he’s sure he killed in Vietnam. They convince him that he didn’t, but he knows in his heart that he did. He has this monologue that’s just on him where he’s finally going to say to the other family: “I think I’m the one that shot your son.” Without scenes like that I think a film would be quite dull. Not that it was, but in the sense those are the emotional parts that speak right to you as a human being, and films whether an action piece or not, it’s just great to have moments where the words are speaking to you.

It was quite interesting whether we could take that with The Pyramid Texts and sustain it for 98-minutes. That was a challenge in itself and I thought: Are we overdoing it? Is it going to hold up? Thankfully it did, because as you said the words were a narrative in itself.

A filmmaker once made the comparison to me that the writing of the script is like composing the score, while directing is standing on the podium conducting the orchestra. In your minds is there a musical dimension to the filmmaking process?

Secondly, James’ performance is poetic with its own musical rhythm. The words are entrancing, almost as if they exist on a different level of consciousness. So there is the separation between the visual and the verbal, but the film merges these levels of consciousness that lend it a power and allows it to work in the form it’s in.

LS: It’s interesting that you pick up on that. We went through many stages of working out how we were going to present the story, and the one thing that we always tend to do when we want to translate the script onto the screen is look for the simplest and most powerful way of doing it. If you sum up our directing style then I think those two words [the visual and the verbal]… We say those to ourselves often, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we’ll be doing the same thing on each project. We allow the film to tell us what’s the right way of translating it onto the screen, and for us simple and powerful on this film was not stripping the direction back to the minimal, but working out what were the most powerful things on the screen — it’s James, it’s the words, and we didn’t want to be ostentatious in the way we directed it.

We wanted people to get lost, to fall into a trance because we felt that was the most powerful way to interpret it, rather than being all MTV and fancy about it. Our initial thought was: Wow, a monologue, 90-minutes. It might be a bit boring for people, so let’s counter that with making it a bit flashy. But we quickly realised when we sank into that visual world that it would counter it and we just wanted to just sink in with those strengths.

I don’t know if that answers your question, but it’s probably, well it’s not probably, it is why we shot it in black and white because it was a very colourful place, and again we didn’t want people to get distracted. In the same way, shooting in black and white, slowly getting closer and closer to our subject, not repeating a shot drew us towards James and his character. Also by keeping the takes quite long and allowing the words to just permeate over you, we wanted everything to be in synch.

This was our debut feature and when we sat down to work out visually how we were going to conduct, as you call it all the pieces, we just listened to the story and the project itself. This influenced us to then direct it in the way that we did and that’s why we didn’t over-score it. We love powerful music, but the most important thing for us is to earn those moments. It’s great because a lot of people have picked up that it wasn’t over-scored, and when it did we felt like it had been earned. It is all about earning those moments, earning the big moments and the ending, but you have to allow for that onscreen and not rush it.

When I interviewed Carol Morley for Starburst for The Falling she explained: “You take it 90 percent of the way, and it is the audience that finishes it. So the audience by bringing themselves: their experiences, opinions and everything else to a film is what completes it.” And if the audience are the ones that complete it, does it follow that there is a transfer in ownership?

LS: I’ll just answer it in a very simple way. Particularly with this film or the ones that have powerful messages, they will resonate differently with different people, and we have certainly found that with the reactions we’ve had to The Pyramid Texts. On the first screening, we did I remember one guy came up and apologised because he had to leave really quickly after the screening. Later we found out he was so moved by the film that he went home, woke up his children and just wanted to tell them that he loved them. That’s how powerfully it hit him.

Since the screening at BAFTA I’ve been messaged by certain people saying it resonated in relation to the themes of fear — feeling ashamed to feel fear, what it means to feel fear and how you can use fear to move on with your life. So I guess people at different stages of their lives will relate to the film in different ways. It has universal themes, but I think it definitely goes deeper, and that depth is related to the person watching it and how they personally interpret it.

PS: Everyone to a certain degree experiences fear, but in different scenarios and circumstances. So just because of the concept alone, all audiences will have connected to it, taken it from the film and applied it to their own life.

It’s quite an interesting question. So do you mean how it resonates with them or when you say ownership, does that mean resonating?

In the cinema the director is regarded as the author, but does a film exist before it is seen by an audience? Film, in spite of being in a permanent form as edited and scored, is actually impermanent. This is because our response can differ each time we watch a film based on our current mindset and the memories it stimulates. So the process of a film being watched by an audience changes the film because it is the individual spectator that creates its identity, leaving film in a permanent state of flux.

PS: Oh I see, that’s a really fascinating concept because who is the auteur or author of the film? The director would have one view or message, but that message is essentially their own. It makes sense to them, but when it comes out and someone else views it, then it will take on a completely different meaning. I don’t think there can be one…

This is going slightly off the subject, but that’s always fascinated me, who is the author of a film? You can’t discount the contribution of an actor and so you could have Quentin Tarantino having made a film with Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder, and suddenly their contribution is invaluable. Suddenly it becomes two artists in one group. Film has so many contributors, and those contributors are artists to a certain degree.

The Fisher King [Terry Gilliam, 1991] also comes to mind. Many would say Terry Gilliam is an auteur in his own way, but then you add Robin Williams into that film and suddenly you are adding another huge individual voice to that project. Painting is different because you have one artist behind the canvas. The question you’ve just raised is really interesting because even if there’s one artist, it can take on a completely different meaning because they’ve now released it and it’s gone into a different life.

LS: That’s three dead comedians you’ve mentioned in the past…

PS: I know. But I’m just saying, because those were the three that popped to mind. The point with Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor was that whatever film they were in, if you see all their films together you can see a common thread. So no matter which director directed them, it didn’t matter because they came in as Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, and it was undeniable that they brought with them their own artistry.

I know there’s a story that Marlon Brando would do three takes of a scene and he would pay attention to which take the director shouted “Print”. He would do one where he’d really dig deep, that was above and beyond what was in the script, and he would do another that was exactly what was written on the page, no more, no less. If the director printed that one he would say: I’m just going to coast this. Why try harder because they are not seeing what I’m trying to do?! So it’s interesting as to who’s responsible for a film because who is responsible for a film?

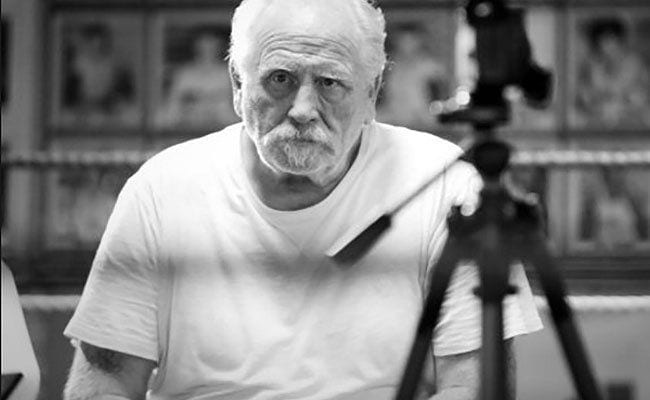

The Shammasians on set of The Pyramid Text

The Pyramid Texts released on iTunes, Amazon, Google Play on 28 April 2017.