When Art Spiegelman’s Maus II premiered at number 13 on the New York Times nonfiction best sellers list in 1991, graphic memoirs became the comics form’s most prestigious genre. Since Maus II had been listed on the fiction list until Spiegelman wrote a letter to the editor describing it as “a carefully researched work based closely on my father’s memories,” the change happened literally overnight.

Frank Santoro would have been 18 and starting his first self-published comics zine then. According to his graphic memoir, Pittsburgh, he was more interested in Spider-Man and Aeon Flux than documenting family memories. But not only is the 40-something Santoro able to explore those memories now, he’s capable of expanding the limits of the genre in the process.

I’ll admit part of the memoir’s appeal to me is personal: I grew up in the Pittsburgh area (Penn Hills); the author and I are similar ages (okay, I was 25 in 1991, but close enough); and my parents divorced, too (though mine didn’t wait till I was 18). Unlike Spiegelman, who opened the door to the graphic memoir genre, or Alison Bechdel, whose 2006 Fun Home raised it to even higher literary prominence, Santoro’s subject matter is unremarkable in summary. He’s one of a demographic of kids whose empty-nest parents divorced while he was a first-year college student, and he places the continuing history of his parents’ estrangement at the center of his memoir.

Though specifics add flesh to that familiar skeleton of a family story, Pittsburgh offers more than just “story” in the usual sense. Santoro’s graphic memoir is most significant for the “graphic” half of the term. It’s a comic, but a comic that cannot be translated into another medium (including prose summary here). Its story is told not simply in pictures, but in a style of image-making that has no counterpart in prose or film or other medium.

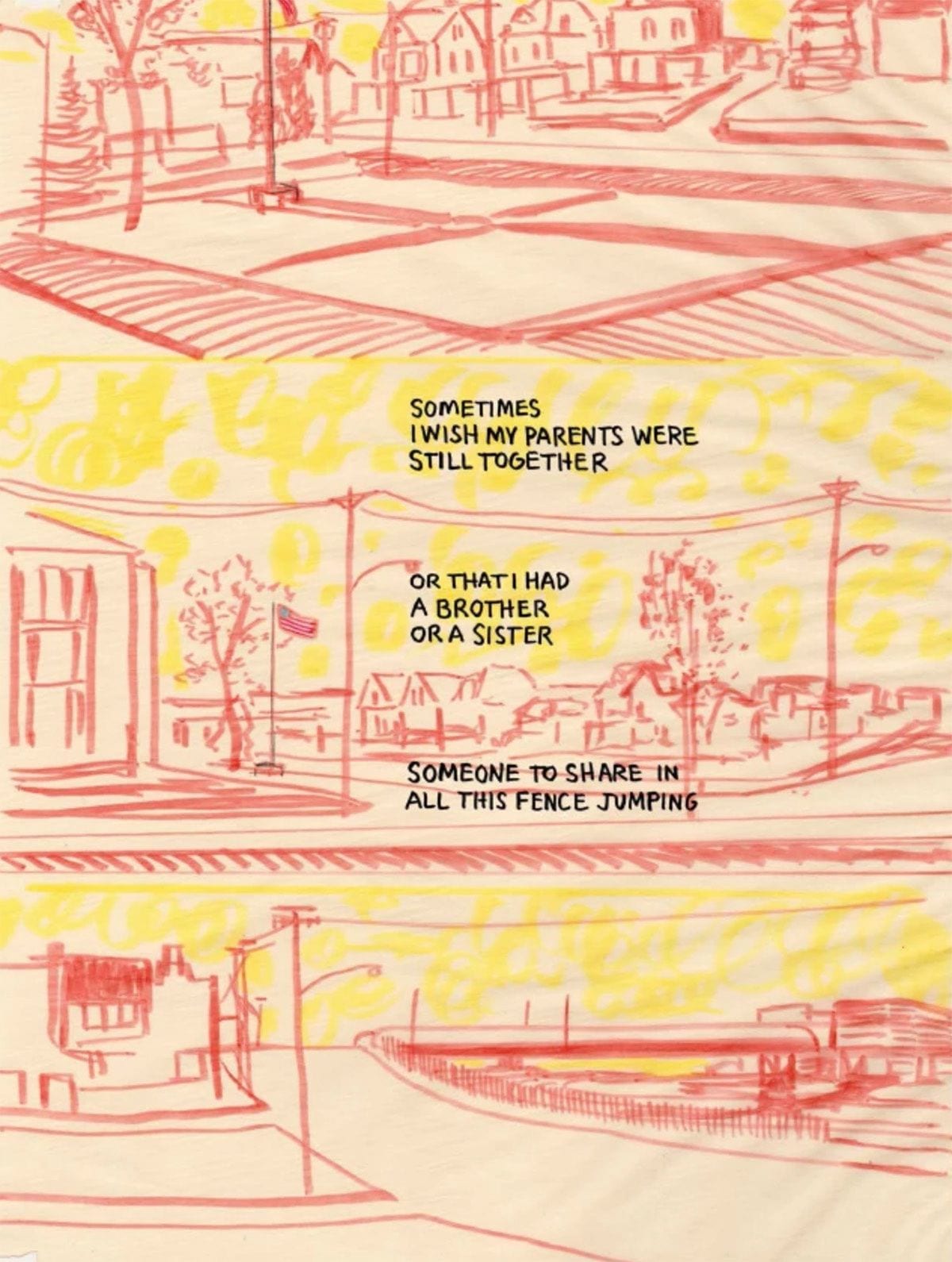

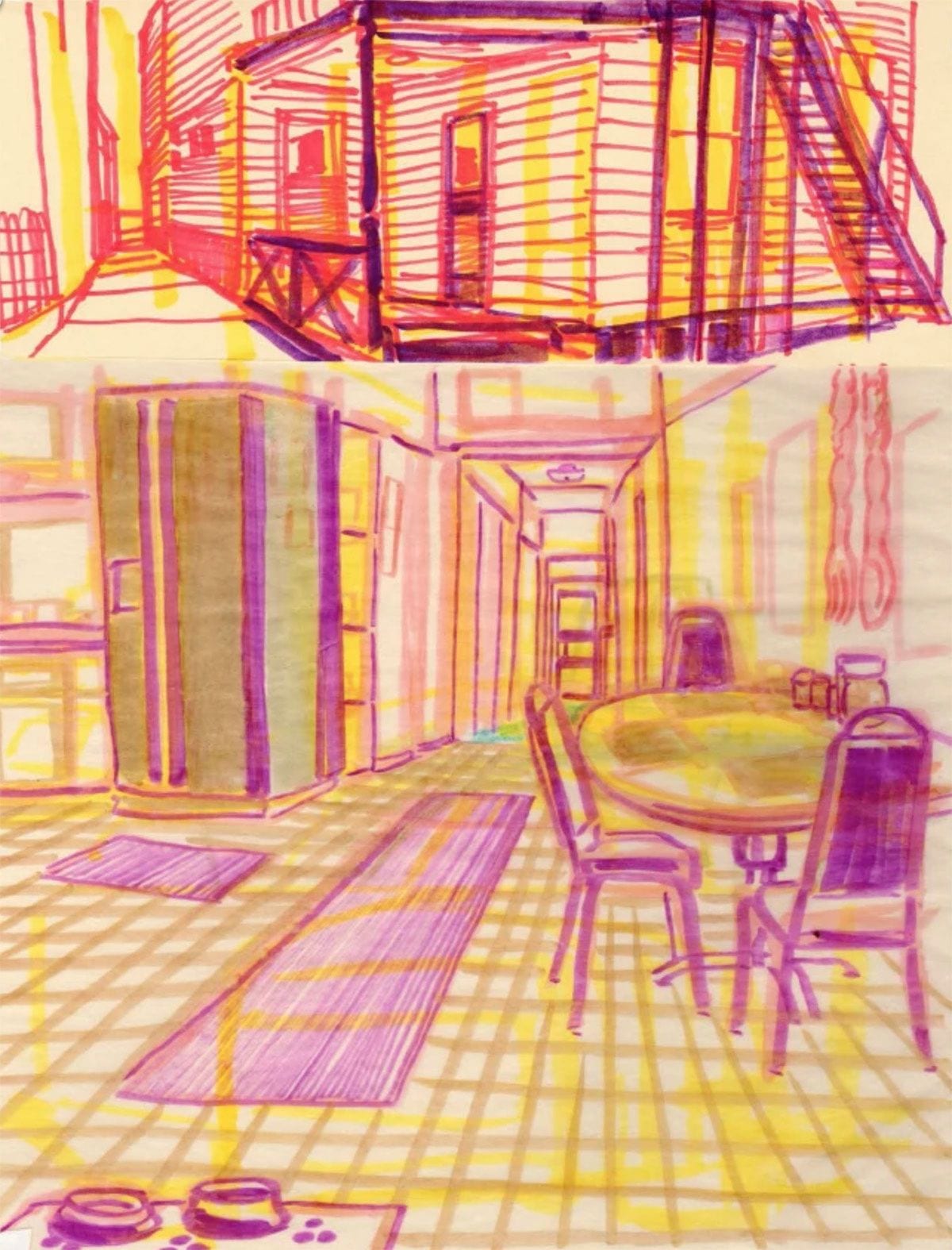

Open to any page and you’ll find the photo reproduction of a yellow piece of paper covered in colored marker. The paper looks like the kind of yellow construction paper I used too, that we stuck under magnets on refrigerator doors across American suburbia. Santoro even shows the wear of wrinkles on the paper. Those imperfections could be corrected in Photoshop, but he’s aiming for the opposite aesthetic. His pages look like they’ve been lifted directly out of his childhood.

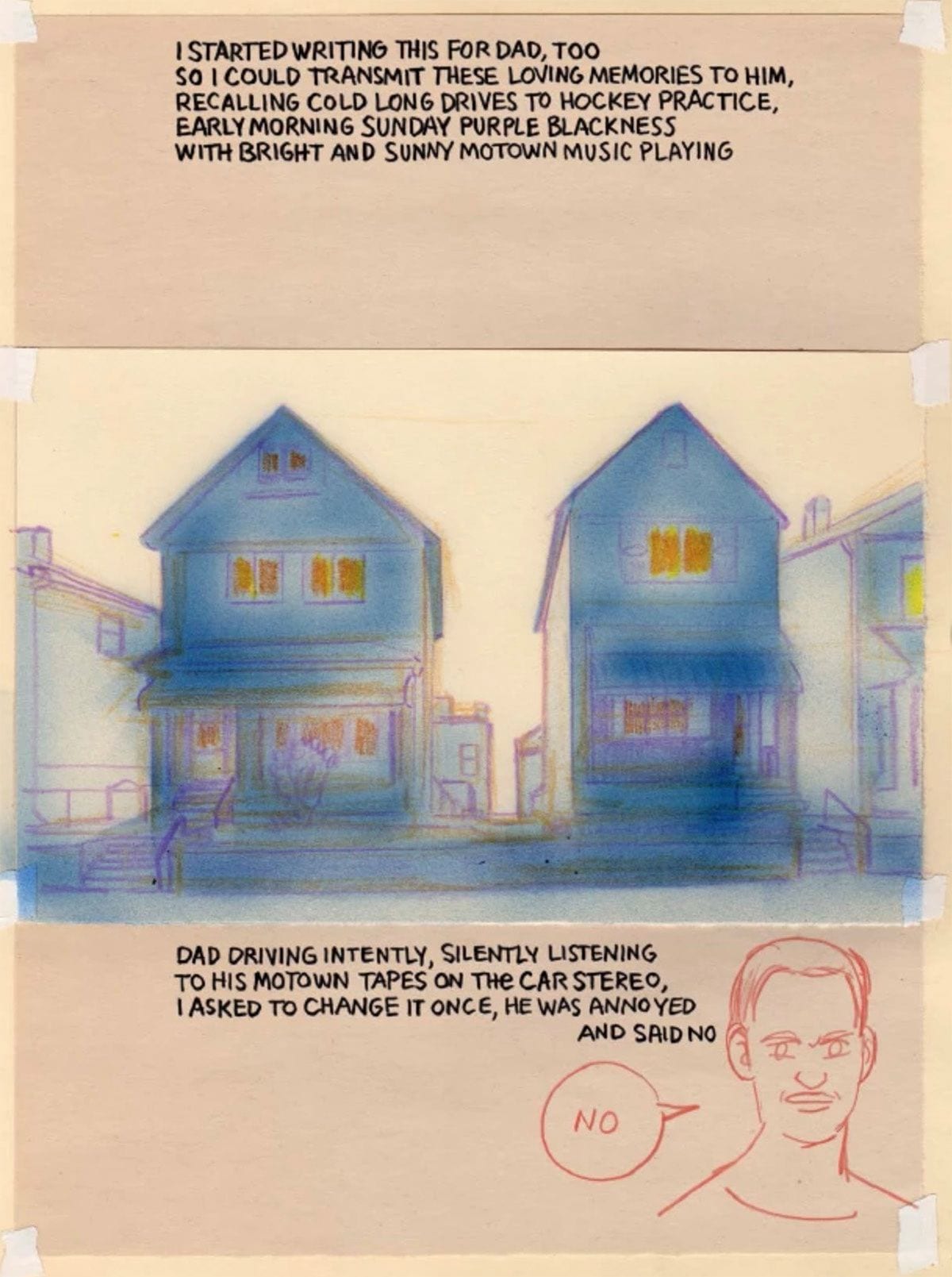

And yet his style isn’t childlike. It fluctuates between quick gestural sketches and carefully crosshatched portraits. Even the most naturalistic images retain rough energy, and the two styles are often superimposed. Traditional comics artists sketch in pencil and finish in black ink, leaving white areas for a colorist to fill later. Santoro overturns those norms. The still-visible bottom layer of his images are colored marker, variously thick- or thin-lined, sometimes gone over with additional marker lines in contrasting color and thickness. The colors—purple, red, blue, yellow, green, brown—seem to have been selected with a child’s intuitive randomness, with no regard for the colors of the real-world objects being drawn.

Santoro also leaves the internal spaces of his figures open, allowing previously drawn images to remain visible. For example, his grandfather sits in a chair and the lines that compose the chair can be seen behind the lines that compose the body. Though the shapes of both sets of lines are naturalistic, the combined effect is not.

Other times Santoro superimposes images with the aid of paper cut-outs and tape. Sometimes the cut-out paper is the same opaque yellow; sometimes it’s tracing paper that mutes but doesn’t block the images underneath it. The always-visible tape is even stranger, as though the entire book were a mock-up of some idealized but forever-undrawn finished version. The effect is odd and oddly poignant. For some reason, the sight of the family dog Pretzel taped beside a drawing of Santoro’s mother on their front porch resonates deeply. Perhaps that’s because the intentionally clumsy construction emphasizes the imperfection, and so the transitory quality, of the moment.

That metaphor runs under every page. His parents’ estrangement reduced his world to a permanently unfinished preliminary sketch. If the structure of his family is so unstable, so provisionary, then his entire universe may as well be constructed of cheap paper that’s held together by bits of tape.

In short, Santoro’s style is idiosyncratic. As it should be. A non-idiosyncratic memoir would defeat its purpose. While that’s arguably true of all memoirs, it’s especially true of graphic memoirs. If Santoro rendered his family members and neighbors in the generalized style of __________ [fill-in any name from the long list of renowned graphic memoirists], then he wouldn’t be documenting personal experiences. Instead, his work would be but a knock-off world peopled by familiar figures who happen to be performing parts in his family story. Though divorce may be a generalized story, the divorce story in Pittsburgh is not, because of Santoro’s artwork.

But Santoro’s approach to that story is effective in literary terms too. There’s a pleasantly odd looping effect to his story, where a handful of moments keep returning in slightly different forms. They’re sometimes retold from a different point of view. (Did his grandmother really threaten to send his mother to an asylum if she married his father? Did his father really leave because he couldn’t bare refereeing his drunk brothers-in-law?) Like the layered pen strokes of Santoro’s images, each layer would be sufficient to communicate the content, but something deeper happens through the accumulations.