Pola Oloixarac’s Dark Constellations is what the late Michael Crichton might have written if he had grown up in Argentina and fancied himself a high postmodernist. As a rule, I dislike such comparisons: let artists speak on their own terms, and not be described as a mix of this and that other creator. But there are times when comparisons truly suffice and are more elegant in their brevity than in their attempts to pinpoint just who and what this “new” voice is. Oloixarac is certainly a new powerhouse in the contemporary literary scene; an Argentinian living between Miami and Buenos Aires, writing for the top Anglophone lit mags, penning opera librettos in between dense novels about intellectual life and politics that are inevitably described as philosophical.

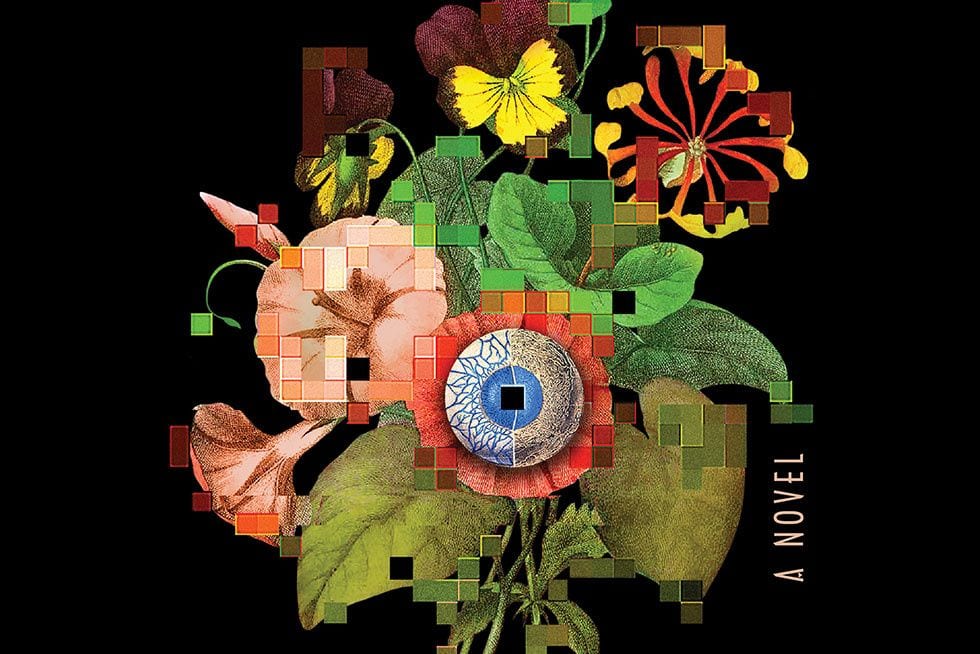

Oloixarac is both highly educated and adept at traversing the narrative ins and outs of intellectuals’ lives, as she showed in her first novel Savage Theories (Soho Press, 2017). But in her turn toward experimental, literary speculative fiction—or what some critics and the market call “slipstream”: science fiction that doesn’t want to generically self-identify—she exudes all the qualities of thought-provoking writing without managing to provoke thought. As a result, Dark Constellations is a bland novel stuck between genres and ideas, switching between timelines that unfold in 1882, the 1980s-90s, and 2024. It should be fascinating, and at times it is; it is beautifully written, the language limpid and poetic when it needs to be, sparse and rugged when the scene calls for it. But Dark Constellations is ultimately a mess of references, of tried stories, and old tropes pining in their mashedness for pastiche, but never coalescing into anything as artful and intoxicating as the mystery plant at the novel’s heart.

In the 1880s, we encounter Niklas Bruun, a botanist in search of Crissia pallida, a hallucinogenic plant that looks like “a reorganization of human eyes—of the entire human face”; his search brings him to the Empire of Brazil and through encounters that blur boundaries between bodies and biologies. In the 1980s-90s, we follow the Brazilian-Argentinian Cassio Brandão da Silva, a chubby nerd genius and computer hacker, and an asshole to women because his crush once dissed him; he grows up, gets in trouble for hacking in college, and gets recruited into financial success as the brains behind a new tech company, Stromatoliton. Sounds about right for the Southern Cone’s iteration of Silicon Valley.

In 2024, Piera joins Stromatoliton as a biologist working on a project to sequence DNA alongside data gathered through government surveillance and newly implemented citizen registries, the whole purpose of which is to create a cache of data that can theoretically predict individuals’ actions and life courses—not unlike Philip K. Dick’s precogs in “The Minority Report” (1956). Cassio and Piera’s tales intertwine, with Piera showing some sexual interest in Cassio and the former agreeing to help sabotage his company and the biosurveillance technology for the good of humanity (he recalls the ethical commitment to democratization he had during his hacker days) and his dick.

The storylines following Cassio and Piera converge nicely, but leave the question of their relation to Niklas. (Oloixarac did something similar in Savage Theories; we’ll see if it continues to be her thing.) There is little tangible connection, but the search for Cassida pallida and the knowledge it might unlock, the new world it anticipates, resembles Stromatoliton’s search for new methods of biopolitical control. Moreover, the stories in Dark Constellations all take place on the verge of techno-scientific breakthroughs that exist within the context of particular imperial times — a preceding moment of exquisite transformation in scientific knowledge. If the late 1800s saw the consolidation of imperial powers and the emergence of wholly modern sciences, and the late 1900s saw the transformation of modern capitalism into neoliberal (neo)imperialism abetted by the technological advances gained through the scientific leaps of the postwar, post-atomic world, it is not far-fetched that Oloixarac imagines a new world transformed by biosurveillance computing technologies in a very near future when Latin America has risen to geopolitical and economic prominence.

In the end, and as a result of the further solidification of neoliberalism such that the global markets ultimately care little if the Global South or the Global North (as messy as those conceptions are) holds the cards, Oloixarac points out that none of Cassio’s actions to thwart Stromatoliton and the state-and-corporate-controlled privatization of its biosurveillance technology mattered—at least at the macroeconomic level: “A war had erupted inside the economic machine, and nothing had changed.” Oloixarac smartly pinpoints the design and story of neoliberalism—to carry on and grow stronger, whatever the market’s temporary variations and crises—and she figures economy as a biological entity that evolves and adapts, like a virus or a slime mold or a stromatolite to its changing conditions. This is perhaps the only useful critique the novel makes: a former hacker with the gender-political leanings of a #GamerGater, enamored of Piera because she is both “more Snow White, more Monica Lewinsky” than any woman he has known, decides he has principles after all and fucks over the company he built the tech for, leading to the “democratization” of biosurveillance data and the technologies for tracking it (ignoring, of course, that the democratization of information is always stratified and has, historically, always been useful for ends just as nefarious as they are benevolent).

Dark Constellations is almost a vignette from a Roberto Bolaño doorstopper, pared down and then stretched out to fill the requisite length required to be printed as a novel. It is two and a half novellas, only one of them remotely intriguing, thrown together in an e-doc and emailed directly to the printer. Alone, Piera’s story is the opening chapter of a Crichtonian techno-thriller; Cassio’s story is the mopey beginning and end (no middle, no story, no character development) of a mediocre Gibsonian cyberpunk novel; and Niklas’s story is the only interesting one among the bunch, which has a bit of Poe’s 1838 Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket to it. On the whole, though, individual paragraphs and scenes in Dark Constellations hold brief attention, but for the most part these are the ones that blur seemingly into non-fiction by giving, for example, a plausible history of the rise of the start-up industry and its outgrowth from Nazi emigres to Argentina who came to prominence under Peron’s dictatorship, or by providing a possible road map for South America’s rise to global prominence via biosurveillance technology and a geopolitical strengthening of the region against Euro-American interests.

But the characters are lifeless and drab, used up copies from three decades of novels just like this—or, well, the various parts of this that resemble the things that have inspired Oloixarac. The story is what you might expect from a TV movie you started halfway through after dinner with your in-laws, your partner’s father already snoring in his La-Z-Boy, even though the pseudo-action of it was meant for him. But Oloixarac is going for something grander than William Gibson’s 1984 Neuromancer (which gets a name drop from Piera, who seems Oloixarac’s double), or Paolo Bacigalupi’s novels, which it seems to be a poor slipstream imitation of, and she would likely find the comparison to Crichton insulting (despite Crichton’s often prophetic, if sometimes pedestrian and tediously technical, visions). She interweaves narratives, timescapes, and even perspectives (an occasional “we” or “I” in an otherwise wholly third-person story; shifting tenses that hardly seem a translation error) to grasp at something like literary complexity—only, without crafted purpose. It’s thus a novel that takes a month to read; not because it’s difficult and writerly, not because it demands the reader sit and reflect, not because it is so packed with genius that you just have to breathe and think about what it all means, what its implications are, and what great truths Oloixarac is digging out of humanity’s dark past and haunted present; but because it’s an exercise in generic, narrative, and aesthetic tedium.

Dark Constellations is the worst of slipstream and of attempted postmodern experimentality at a time when attempts to be the Pynchon or Nabokov of the ’60s are, frankly, boring. The novel does nothing—says nothing unsaid by every movie, TV show, comic book, Twitter thread, and TED Talk since the Patriot Act—and will be a critical hit all the same.

At least it has a cool cover.