The story of Aaron Sullivan is out there. It’s been out there for some time, a sad narrative supporting a sad statistic. Chances are, you’ve read or seen hundreds of stories like it in the local papers, on the local news. “Gone too soon.” “His whole life ahead of him.” The story is here. By most accounts, an argument led to hurt feelings, which led to a gun, which led to tragedy. It’s a microcosm of so many of the parts of day to day life that we wish we could pretend didn’t exist.

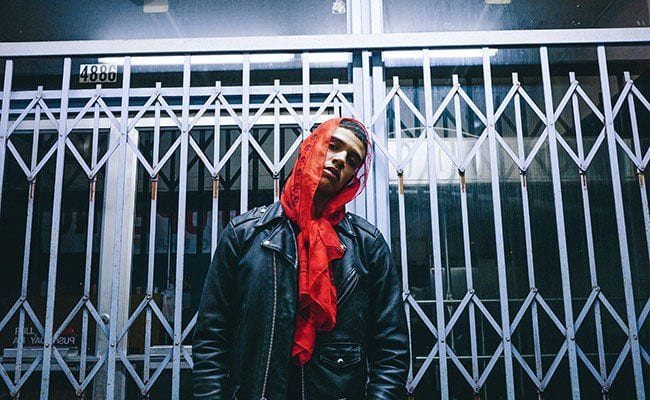

Aaron’s brother, one Porter Ray Sullivan, is using his debut album for Sub Pop to make sure we can’t pretend any such thing.

There’s a haze to Watercolor. It’s the haze that comes with memory, the slight fuzziness to the past that keeps us from remembering every detail but allows us to remember the important bits all too clearly. The production exists largely in the clouds, an unassuming wash of synths and beats that never begs for attention or distracts from Porter Ray’s message. Porter Ray’s rapping style is relaxed but quick, a style that emphasizes the intellectual bent to many of his rhymes, but intentionally fails to prepare you for the full weight of his message.

To be sure, it hits hardest when you’re not ready for it.

Aaron is referenced by name throughout Watercolor. He’s Porter Ray’s “brody” throughout the album. He gets a full eight bars on “East Seattle”, a picture in an album full of the temptations and consequences of hard living in Seattle. He gets almost all of “The Mirror Between Us”, a shattering account of losing a brother to gunfire and a friend to jail, a document of the crushing transience of personal relationships. And then there’s “Navi Truck”, a track which on the surface has nothing to do with Aaron. “Navi Truck” is actually about the women in Porter Ray’s life, those who have wronged him, those he has wronged. A little more than halfway through, we find out that he had a baby with one of these women: a son named Aaron. In the context of the song, it’s a small detail, but given the tales told throughout the album, it is a mark of the complexity of the lives that Porter Ray, his friends, and his family lead.

If it doesn’t sound fun, that’s because it’s not. Most of Watercolor is a grim, heavy listen. The tracks that aren’t about the big events in Porter Ray’s life are about the everyday injustices, the trappings of street life, the difficulty of trying to do the right thing and coming up short. The title of “Sacred Geometry” — one of the more upbeat numbers here — is a reference to the apparent symmetry of motion when trying to make something of yourself. Two steps forward, two steps back, or, as the Palaceer of labelmate Shabazz Palaces puts it: “What goes up, gots to come down.”

There is hope to be found. “My Mother’s Words” builds a rap around a recorded conversation that Porter Ray has with his mother; a mother who clearly, despite all of the hardship she and her family has been through, sees great things on the way for her boy. “Careful, you signed your deal / Success will blind you still,” Porter Ray raps over and over again, words of caution amidst words of hope as if he is reminding himself not to forget. The track ends with an extended monologue from Ms. Sullivan; “You have become the educated scholar I always thought that you would be all along. And it didn’t take a school to get you there,” she says, and you feel Porter Ray’s pride, pride in his mother, pride in himself.

Sometimes Watercolor is so subtle and unassuming as to risk being too easy to ignore, but it never actually gets to that point. Porter Ray might fall into rap tropes every so often, but he also finds his way out through those touching points of family, tragedy, and where the two intertwine. Mostly, it’s a fascinating listen that requires a few times through to really connect with the vibe before you can fully appreciate it. Give it the time, though, and you will appreciate it, and maybe you’ll even appreciate your life a little more, too.