It’s too early to mourn the passing of Koyama Press since they’re not scheduled to close shop till 2021. But it does add a bittersweetness to each new release, like starting the final season of your favorite TV show, or really your favorite network, since Koyama’s new release list is like a prime-time schedule heavy on returning hit series. Keiler Roberts, Michael DeForge, and Patrick Kyle have each been with the press for several years, and all have new works premiering.

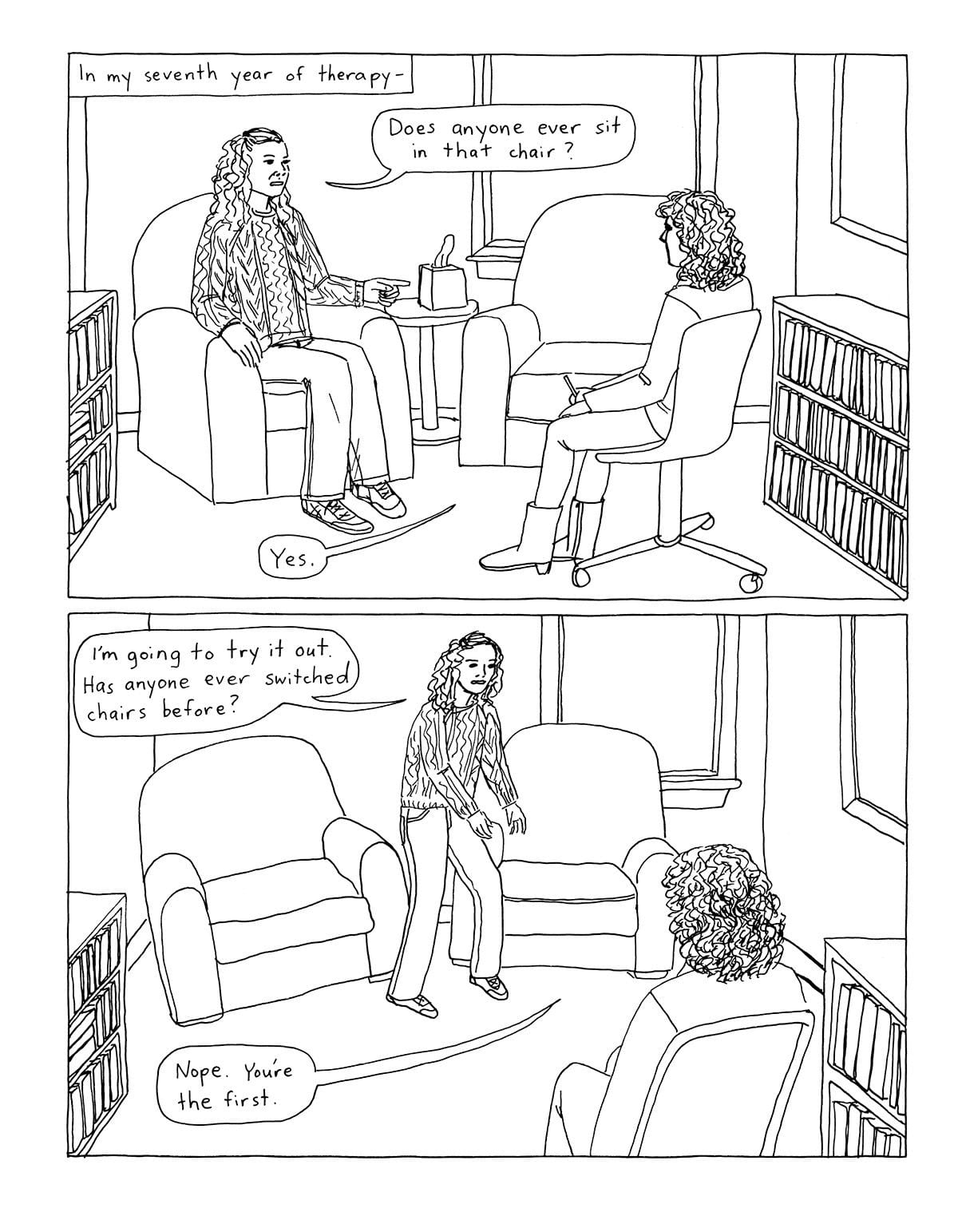

Only Roberts’ Rat Time is literally a continuing saga, picking up where her graphic memoir Chlorine Gardens left off last year. She draws her school-age daughter Xia a little taller here, but the rest of her cast of family and friends are the familiar minimalist line drawings of before, their world still composed of the same thin black lines as the gutters framing it.

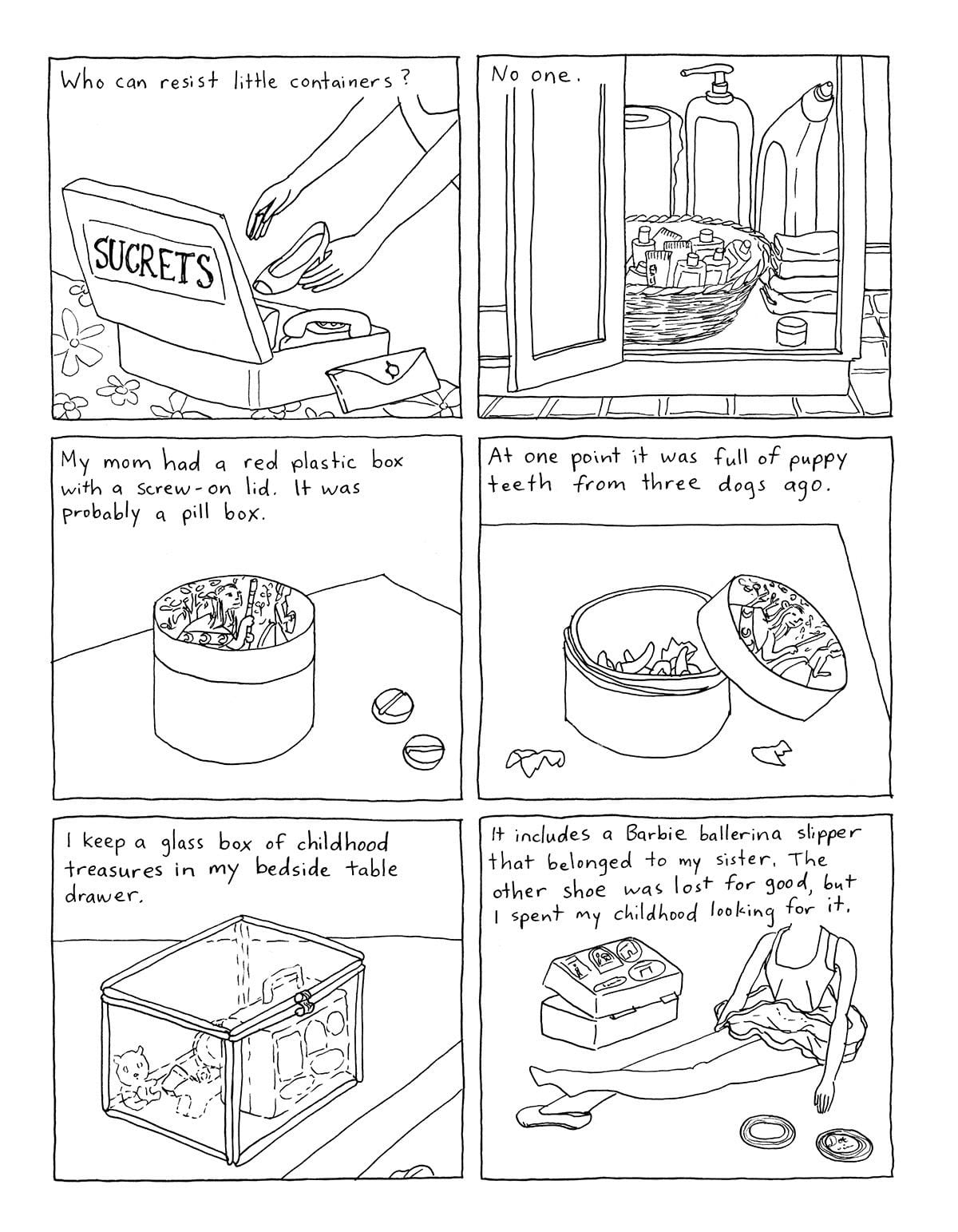

Though the effect is a species of realism, Roberts has no patience for crosshatching, leaving the interiors of her shapes intentionally flat and shadowless. Though animals and Barbie doll faces tend to be more precise than humans, when Roberts fully breaks style with a suddenly detailed and naturalistically rendered image (always, it seems, of a dead family pet), it’s a reminder that the rest of the book’s rough shapes and choppy lines are not determined by the limits of her skill but by the choices of her stripped-bare aesthetic.

(courtesy of Koyama Press)

On the back-cover blurb, Lisa Hanawalt calls Roberts’ books “diary comics”, but I disagree. For an actual example of a diary comic, checkout Eleanor Davis’s You & a Bike & a Road (2017) which was composed as an actual diary one entry at a time. The flow and arc of Rat Time are too artful to be the product of daily happenstance. These aren’t snapshots in a family photo album either. Roberts wanders unannounced into memories ranging from playing with her childhood dolls to teaching her first catastrophically bad community college course. The transitions are brief and intuitive, providing just enough structure for the juxtapositions to do the storytelling. (Xia plays with dolls too; skeletons are more useful than cadavers when teaching drawing.)

Maybe “story” is the wrong word. Although the one- and two-page family vignettes are punctuated with scenes in her therapist’s office as Roberts continues to struggle with bipolar disorder and early stages of MS (plot points carried over from last season), the story doesn’t feel plotted and certainly not dramatic. Roberts is aiming for the opposite effects, rendering a kind of gently comic, low-suspense universe made more realistic by its absence of artifice.

When Roberts attempts to write fiction, it has an uncanny resemblance to the nonfiction of her life. Even when she plays dolls with Xia (it must be an inheritable trait), Roberts can’t escape mundane realism. That’s a good thing. Though she foreshadows the book’s likely closure point when her narrator declares, “I’m either going to figure out how to write fiction or get a better idea of why I don’t,” neither of the promised outcomes transpires. That’s because foreshadowing is for fiction. She already knows why she doesn’t write fiction. It’s too contrived. So is traditional memoir, which is why she’s a master of understatement and inference.

Roberts doesn’t have to tell her readers that these recollections of dead pets are really about her aging parents and the not-yet-detectable decay of her own body. Stating it would make it too dramatic, too obvious, too much like fiction. The pets are also about the pets. Roberts’ mother worries she touched the dog more than she touched Roberts as a child, but that’s okay. The transitory companionship of animals is superior to human companionship in many ways.

(courtesy of Koyama Press)

Some of the most touching moments in Rat Time are full-page, uncaptioned images of pets and humans in quiet contact. Since backyard burials and memorial photos are an ever-expanding multi-generational tradition, it’s good that pet shops provide an endless supply of dogs and rats. (The Roberts family has a thing for rats.)

The phrase “Rat time” originated as the after-dinner time when Xia played with her pets. After she cycles through a few almost identically named rodents, “rat time” comes to resonate with absence too. While Chlorine Gardens readers will recall the recent death of Roberts’ grandfather, Rat Time only nods at it through his unacknowledged absence and her grandmother’s unremarkable singleness. This is just how things are. No need for drama or commentary. When Roberts showed Michelangelo’s Pieta to her first Art History class, she was embarrassed because she had nothing to say about it. Though “Let’s all just look at it for a few minutes” isn’t the best lesson plan, it’s not a bad life strategy.

Roberts takes us through a curated set of vignettes, creating a fragmented but still cohesive flow of events that resists the norms of plot while still providing its pleasures. There as many small and touching and gently comical moments in this story. There’s a fond memory of a self-effacing professor and her imaginary Dear Gratitude Journal filled with ironic absurdities. She makes her therapist laugh by saying their work here is done. There are cooking and tampon catastrophes. She makes a list of things that make her cry and a list of things that makes her happy.

The story has the logic of a list, as though Roberts is still assembling it, still thinking through each entry even as she jumps to the next. The past has that open-ended feel too. That self-effacing professor accidentally lost a ring while lecturing, and the sound of it bouncing away stays with Roberts. She still wonders if the woman ever found it. One of my favorite images is Roberts sitting on her bed surrounded by open books with the narrated caption: “It doesn’t bother me to read parts of books and never finish them.” Again, not a great lesson plan, but it’s the only life strategy there is.

(courtesy of Koyama Press)