The best punk, like the best humor, packs a critical punch, and no music genre has unleashed the weapon of wit more regularly and eclectically than punk has. This should be of little surprise since punk inherited its aesthetic DNA from the most subversively humorous art: dada, surrealism, and situationism. Like those expressive art movements, punk does not so much employ humor into its critical arsenal as express it as its very essence and being.

Humorists have served as the conscience of cultures ever since (and before) court jesters ridiculed omnipotent royalty for its hypocrisy, pomposity, and corruption. From the Sex Pistols’ sneering take-downs of the contemporary royal court to Green Day’s wide-eyed dramatizations of American idiocy, to Pussy Riot’s performative prank-activism against Putin’s church-sanctioned patriarchy, punk continues to fulfill that essential jester role in relation to the powers-that-be of the modern world.

Punk humor is humor with a purpose, even when it is at its most infantile or trivial. To operate it requires an opposition, a source of conflict. That may be a social institution, cultural mores, or music itself, anything antagonistic to the point-of-view of the punk purveyor. Whatever the target, punk humor can attack in multiple ways — directly through lyrics or maybe more obtusely through music style, performance, or image. Sometimes a dance move, hairstyle, or album cover can be the means by which its combative humor is conveyed.

Punk humor, like much social humor, derives its potency from its tribal nature. It’s not intended to be appreciated or accepted by all; indeed, its need for an opposition necessitates that it not be. Instead, it preaches to the choir, offering empowering sustenance to believers and a home for the like-minded. Such a communitarian quality is essential within punk, where its subcultures are made up of myriad outsiders. Punks invariably emanate from the margins of society, where they have felt ostracized due to factors of class, gender, sexuality, or maybe just personality. For them, punk humor validates their outsider lives and perspectives, sometimes challenging them in empowering ways.

As the likes of Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, and George Carlin have demonstrated, some humorists not only remind us—or introduce us to—truths that the ruling class would prefer we were unaware of or complacent to, but they can provide different ways of understanding and digesting reality. By stripping away the obfuscating ideology propagated by establishment powers, subversive humorists operate as alternative documentarians and historians. They see so that we might re-see. The deepest punk humor serves this tradition in ways sometimes coded to speak to the subcultural in-crowd or to circumvent potentially censorious opposition.

As such, punk has much in common with prior “folk” humor, particularly that which emanates from music scenes of decades past. In artists like Billy Bragg and Shane McGowan that tradition is particularly apparent, their communal songs steeped as much in folk humor as in the punk style they wrap them in. Punk humor can thus be seen as both drawing from existing templates of humor while accentuating features specific and purposeful to its own means and ends.

One such distinction is punk’s youth orientation, which is both literal and suggestive. Operating in a pre-adult world, punk humor plays to the natural insolence and dissent of youth, what Andy Medhurst calls “the playground’s subversive delights” ( A National Joke: Popular Comedy and English Cultural Identities. London: Routledge, 2007. p.209). As a result, the expression is invariably more sophomoric than sophisticated, yet the innocence of youth and the authenticity that often attends it are on full display. In presuming a youth audience, punk humor often eschews such “adult” traits as compromise, complication, and deference. Instead, it parades the impetuous nature of youth, questioning norms, complaining, and seeking solace through sarcasm.

Such youthful emissions are often primal in their emotional make-up. Punk’s curses of incivility, combined with theatrical acts of spitting, screaming, and cavorting, speak to Sigmund Freud’s theory of relief humor. The psychoanalyst would—one presumes—see punk as the release of those aggressive and sexual impulses repressed by social rules and controls. Untamed, the id is set free to exercise in its primitive pre-adult state. The consequential grotesque gestures are fundamental to some of the funniest and most outrageous (pre) punk expressers, from Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Gene Vincent in the ’50s, to Iggy Pop, Ari Up, and GG Allin in more recent times.

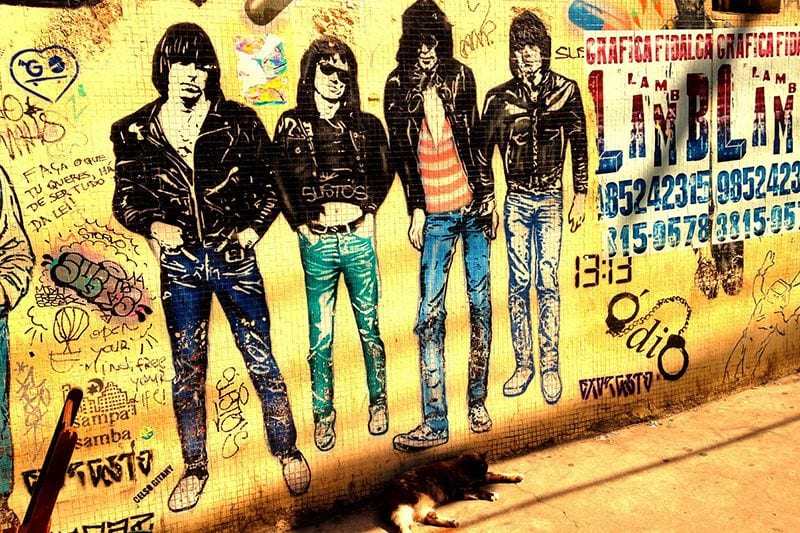

The ubiquity of such wild youth displays has led some to interpret punk humor as largely infantile. However, while punk may act dumb, it can do so with sometimes artful self-awareness, as a display of defiance to the adult super-ego. The Ramones, for example, used their back-to-basics simpleton persona as a form of incongruity humor, submitting a stark contrast to the “adult” pretensions that pervaded the progressive rock of the mid-’70s. Their three-chord songs, minimalist kid-speak, and dropout look were all comedic markers that reminded us of what rock music had become, as well as what it once had been and what it should be.

The kind of calculated ironic poses crafted by the Ramones and others show punk as an art form operating through a sign language that belies the stereotypes of it as simple and stupid. In fact, punk humor, far from one-dimensional, is diverse in nature, with satire, (self-)parody, irony, whimsy, wordplay, cartoon, grotesque, and absurdism featuring among its manifestations. Alas, many ignorant to punk’s semiotics have failed to perceive or understand this humor because it comes in a form coded to register solely within punk as a binding language. From jazz hipsters to hippies to punks, spectacular subcultures have always preserved their autonomy and identity in ways that the outside world does not—and must not—fully comprehend. Their “darkly comic signifiers” (Dick Hebdige. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Routledge, 1979. p.105)—in style, language, and expression—allow knowledge-insiders to unite in a collective scornful laugh at the oppressive forces that seek to systematically diminish their worth.

Besides demonstrating a range of humor styles through an array of outlets, punk has also deployed these means for purposeful social change. Just as the original rock ‘n’ rollers allegorically used outrageous physical humor to rile up the kids, encouraging them to break down the walls of segregation (racial and beyond), so punk has been a trailblazer on behalf of social justice concerns. Again, its humor can often arrive in coded form, as demonstrated in the gender deconstructions of punk and post-punk feminism. When Siouxsie Sioux wore sado-masochistic bondage clothing and struck a fierce dominatrix pose, these were more than shock pranks; they signified that women could inhabit, in assertive and provocative ways, the new spaces punk had carved out.

In assessing the nature of punk, time and place have always been significant determinants of distinction. But can the same be said of punk humor, which has flourished simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic? Debates have long existed about the similarities and differences of humor between the US and UK, leading to larger questions about whether humor is a universal or national phenomenon. In general, as with punk, the answer appears to lie in both propositions, as both are always in effect. While humor styles, forms, techniques, and purposes are common to both US and UK punk, certain strains are more pronounced in each and the distinctions are largely of circumstance and environment, in the local details and vernacular. Regarding the latter, Medhurst comments, “The way the English says things has become more telling than what they say” (p.165). One thinks of the heightened cockney inflections of much early British punk singing, with its deliberate associations to working class identity.

Accent(uat)ed into a linguistic flair for slang and swearing, British punk humor perpetuates traditions from past comedy eras. The Sex Pistols’ ” Sod the Jubilee” campaign in 1977, for example, recalled the Billingsgate Oath from feudal times, when street workers would publicly shout out foul-mouthed abuse against the church and state. Pistols front-man Johnny Rotten notes more recent connections, seeing his band as riffing on the comic protestations once heard from 19th century music halls (The Filth and the Fury. Dir. Julien Temple. New Line Films, 2005. DVD). He argues on behalf of a national character of humor, claiming of the English, “There’s a sense of comedy… that even in your grimmest moments you laugh.” Author Zadie Smith concurs, explaining, “In British comedy the painful… dividers of real life are neutralized and exposed” (“Dead Man Laughing”. The New Yorker. 22 December 2008).

If British punk humor is often overtly political, its American equivalents are perhaps more generally cultural, but whatever the distinctions, both sets of humorists unite in satirizing targets within their business, such as the phonies inhabiting their industry, record companies, and fan bases. Their internal pot-shots resonate as symbolic slights against the broader society, too.

Forerunners from the ’50s, while mostly American, greatly informed the underground bands of the UK during the ’70s. In both image and sound, early British punks bypassed much of the music from their prior decade and went straight to the primitives before for inspiration. Steve Jones’ guitar style, for example, harkens back to Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochran rather than to the blues-rock heroes of the ’60s for its rhythmic, chord-centered riffs. This influence was made explicit during the “flogging a dead horse” dying stages of the Pistols’ lifeline when the band covered Cochran’s “Somethin’ Else” (1959) and “C’mon Everybody” (1958). During the same year The Clash paid tribute to a rare British rocker of the period, Vince Taylor, with a version of his “Brand New Cadillac” (1959) on their London Calling (1979) album. By this time many punks, including the Clash, were dressing more like rockabillies than punks, wearing brothel creeper shoes and shirts with collars upturned; this love for the peacock-like sartorial splendors of ’50s rebel rockers was shared by eagle-eyed Ian Dury, who paid tribute to his favorite cool cat in a detailed and descriptive homage called “Sweet Gene Vincent” (1977). Indeed, one wonders whether Malcolm McLaren, by the end of the ’70s, was beginning to regret turning his once ’50s-styled retro store into a high-priced bondage boutique for wanna-be punks.

What the British punks were attracted to in some of the more outrageous ’50s artists—Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Screaming Jay Hawkins, and Gene Vincent—was not only their spectacular looks but the wild physical humor they displayed on records and stages. Rockabilly stomps and New Orleans-style piano pounding provided the proto-punk backdrop over which these singers yelped, screamed, and teased, unleashing their youthful ids for hungry youths and at horrified parents. These wild ones created an atmosphere of energy, aggression, and abandon that later punks would adopt. Some, like The Cramps, showed that not much adaptation was required to push rockabilly into the more extreme psychobilly that came to the fore heading into the ’80s.

Capitalizing on the fear their outbursts were creating in the adult culture, some ’50s acts, like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, saw opportunities in mixing demonstrative humor with horror imagery. His parody of a demonic savage established the horror-meets-humor marriage that The Damned, The Birthday Party, The Misfits, and The Meteors were later drawn to, setting the stage for the somewhat less tongue-in-cheek goth subculture that still attracts wayward youth to this day.

The ’50s rock ‘n’ roll scene is known for playing more to the fantasies of adolescent males than females, and much of its id(iot) humor is crafted accordingly. However, in rockabilly Wanda Jackson and bawdy blues-women like Big Mama Thornton and Etta James new female identities were formed. Jackson’s “bitch” humor (Joanne R. Gilbert. Performing Marginality: Humor, Gender, and Cultural Critique. Wayne State Uni. Press, 2004) is apparent in songs like “I Gotta Know” (1956) and “Hot Dog That Made Him Mad” (1956), both hilarious boasts that put down inadequate males with curt dismissals. Neither number is far in sentiment from the kind of feminist sarcasm Bikini Kill and L7 would spit out 40 years later.

The most rebellious ’50s rock humor sought to awaken and empower the constrained kids of the tranquilized Eisenhower era. Bare-boned and basic, it shattered taboos, tapped the irrational, and set free the animal within, characteristics punks would later push to even more shocking and exaggerated (and funny) limits. In both periods, although the parents rarely understood what was going on or what these expressions meant to their kids, Freud certainly would have.

Bare-boned and basic, ’50s rock rebels shattered taboos, tapped the irrational, and set free the animal within, characteristics punks would later push to even more shocking and exaggerated (and funny) limits.